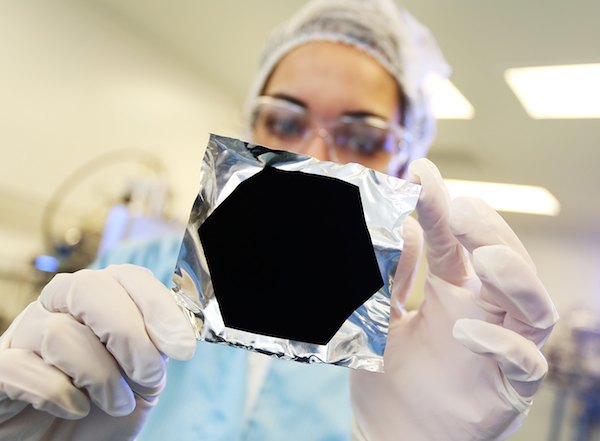

[Image above] That’s not a black hole—that’s Vantablack. Credit: Surrey NanoSystems

The world’s blackest material, Vantablack, just got blacker.

The material, which was developed by U.K. company Surrey NanoSystems a few years ago, consists of a dense coating of carbon nanotubes that absorbs nearly all light that hits the material’s surface. According to the company, “The near total lack of reflectance creates an almost perfect black surface.”

But apparently Surrey NanoSystems wasn’t happy with the almost-perfect status of its black material—the company recently revealed that it has slightly improved its blackest black material to be even blacker.

According to the company, the new version of Vantablack absorbs so much light that it cannot even be measured by spectrometers. Which is probably a rather effective strategy to stay on top of the competition.

The company doesn’t provide any additional information on exactly what it did differently to make the new version of Vantablack its blackest yet, however.

Watch the new material’s incredible light-trapping power in Surrey’s sneak peek video below.

Credit: Surrey NanoSystems; YouTube

But, in general, how does Vantablack suck up such a vast majority of the light that hits its surface?

Surrey NanoSystems grows Vantablack surfaces via chemical vapor deposition of carbon nanotubes that measure just 20 nm in diameter and stretch out in length 14–50 μm.

And Vantablack’s thin and long carbon nanotubes are tightly packed—Surrey NanoSystems says that “a surface area of 1 cm2 would contain around 1,000 million nanotubes.”

According to the company, the length of the tubes in relation to their small diameter and the space surrounding them is what makes the material so effective at trapping light, forcing it to bounce around among the nanotubes.

The materials’ nanostructure traps light so well that it barely escapes—less than 0.036% of light is reflected from the surface (of the original Vantablack)—making a coating of the material look more like nothing than like anything else.

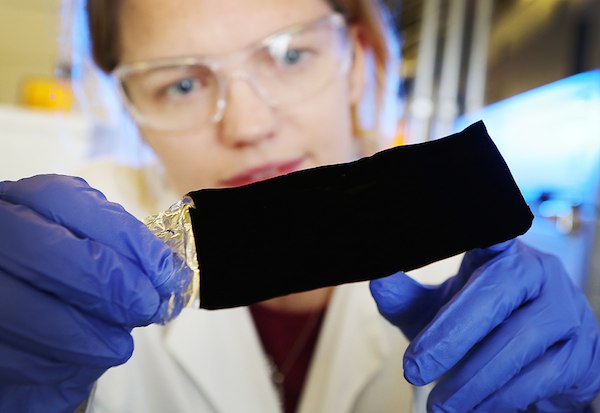

Vantablack looks more like nothing than like anything else. Credit: Surrey Nanosystems

And according to a NY Times article detailing an interview with Surrey chief tech officer Ben Jensen, Vantablack has a production advantage that makes the material promising for diverse applications—growing carbon nanotubes at lower temperatures.

“Growing carbon nanotubes isn’t new,” Jensen says in the article. “But typically they’ve been grown at a very high temperature: 750 degrees centigrade. That would destroy most underlying materials, so they grew them on things like silicon, diamond, and sapphire, which can stand high temperatures. We’re building on work to grow nanotubes at a lower temperature for microelectronics.”

But Vantablack’s impressive properties don’t stop there.

According to a 2015 press release from the National Physical Laboratory, which measured the material’s officially recorded light reflectance, “Vantablack has the highest thermal conductivity and lowest mass-volume of any material that can be used in high-emissivity applications. It has virtually undetectable levels of outgassing and particle fallout, thus eliminating a key source of contamination in sensitive imaging systems. It withstands launch shock, staging, and long-term vibration, and is suitable for coating internal components, such as apertures, baffles, cold shields, and Micro Electro Mechanical Systems (MEMS) type optical sensors.”

In the NY Times article, Jensen indicates that the material could find myriad uses, including ultrablack coatings, microchip wiring, stronger aerospace components, touch screens, and ultralight wiring.

Beyond the many technical applications, however, Vantablack actually might find its first public use as a visual medium of expression.

Artist Anish Kapoor—best known for designing Chicago’s Cloud Gate—recently created a stir when he bought exclusive rights to use Vantablack in art.

But what lines denote art? I’d say they’re blurry at best.

So far, Vantablack is not available for private sale, so we’ll have to wait to see what other commercial uses of this interesting material appear (to disappear).