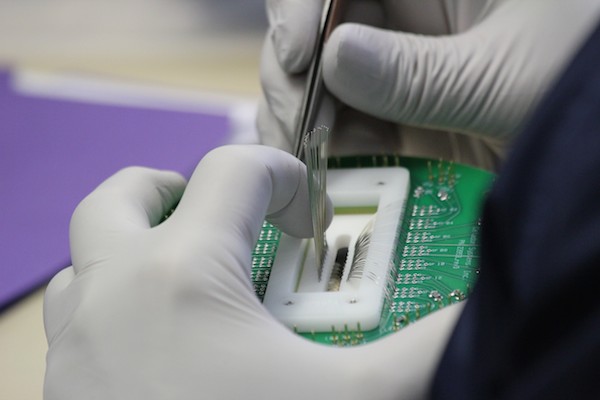

[Image above] Probe cards made with patented ceramic technology by Celadon Systems. Credit: CeladonSystems; Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

Manufacturing is changing.

“Gut feel. Touching things. Making things with your hands. That was American manufacturing…Now, it’s less art, more science. And this is exactly the challenge today,” David Greene writes in an NPR article about manufacturing in the United States. The article is the first in an excellent series called “American made: The new manufacturing landscape.”

ACerS knows firsthand that manufacturing is changing—especially in the ceramic and glass world.

Just last month saw proof that manufacturing is back in a big way, with the success of the first-ever Ceramics Expo in Cleveland, Ohio. ACerS was a founding partner in the ceramic and glass tradeshow, which was organized by U.K.-based Smarter Shows.

The show attracted some 2,400 attendees to browse aisles of booths and swap business cards with over 170 exhibitors displaying the latest products, materials, processes, equipment, and more.

In addition to the tradeshow, ACerS has also been driving several other industry-centric initiatives, including formation of the new Manufacturing Division and launch of the Ceramic and Glass Industry Foundation. And just last week, NIST announced that the Society has been awarded an Advanced Manufacturing Technology planning grant to lead a technology roadmapping effort to identify key needs in the functional glass industry.

Beyond the ceramics and glass world, however, manufacturing is changing in other ways, too.

Part of the changing landscape of manufacturing is evident in stark contrasts between low-tech, manual, and skilled processes at factories like Homer Laughlin’s Fiesta plant and newer high-tech, highly-automated facilities that use robots and other high tech advances, like levitating assembly line rollers.

While a majority of manufacturing facilities don’t use robots—a GE reports article cites that some 90% of manufacturing tasks are not automated—automation is nonetheless on the rise thanks to developments and technology that make robots more precise, agile, and flexible.

However smart they get, however, robots can’t do everything.

The manufacturing facility of RenewABILITY Energy Inc. in Kitchener, Ontario. Credit: Premier of Ontario Photography; Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

That’s a problem because there is already a skills gap lurking around American manufacturing.

As the current contingent of skilled manufacturing workers continues to age and creep closer to retirement, the possibility of a dearth of younger skilled workers to take over those empty positions grows larger.

But the identity—and impression—of just what is required for those manufacturing jobs is different than it used to be.

“The one certainty we have is manufacturing is going to look more and more like computer programming and engineering,” says reporter Adam Davidson in another NPR story in the “American Made” series. “It’s going to involve a lot more brainwork and a lot less brawn work. And that means probably a smaller number of people can benefit, but those who can benefit will probably benefit quite a bit.”

That’s good news for materials science and engineering, among other skilled engineering fields.

Assembly of new cars at a Toyota Manufacturing UK facility. Credit: Toyota UK; Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

But there is disagreement as to just how large the skills gap really is. An American Enterprise Institute (AEI) article cites a report by the Boston Consulting Group (BCG) that argues against the existence of a skills gap at all.

In its report, the BCG concludes that U.S. manufacturers are trying to hire high-skilled workers at ‘rock-bottom’ wage rates, and that is not what it would characterize as a ‘skills gap.’ As Adam Davidson asks in his recent New York Times Magazine article, ‘Skills don’t pay the bills’: Who wants to operate a highly sophisticated machine for $10 per hour? Answer: not a lot of people. As a result, says Davidson, there really isn’t a skills gap. Rather, it’s the unwillingness of manufacturers to pay higher wages that is causing the skilled worker shortage, which is a view that is consistent with the BCG report.

The entire article, although a few years old, goes much farther in depth into the debate. Ultimately, though, AEI disagrees with the BCG report by concluding that the skill gap is not a fictional character in the manufacturing story.

“Although there are some differences in estimates of the magnitude of the current skilled worker shortage in manufacturing, there is general consensus that a skills gap exists and that it will likely worsen in the near future. Fortunately, the issue of the skills gap is generating a fair amount of national media and industry attention, which is bringing some well-deserved debate to an important topic that is crucial to a key sector of the U.S. economy,” the article states.

The Ceramic and Glass Industry Foundation is also bringing some attention to the topic through its mission “to ensure that the industry is able to attract and train the highest quality talent available to work with engineered systems and products that utilize ceramic and glass materials.” For more about CGIF and how it intends to fulfill that mission, head over to Eileen’s blog post about the CGIF Board’s recent first meeting.

What do you think about the current state of, or future trajectory for, manufacturing? What about the skills gap—does it exist, and, if so, what can be done to bridge the gap?