Fake worms, real robots. Credit: NSF Science Nation, You Tube.

Creeping, crawling caterpillars: Roly-poly role models for future robots

Tufts University professor Barry Trimmer is fascinated by green tobacco hornworm and how the caterpillar can move in ways animals with spines and skeletons can’t. Trimmer’s team is trying to understand how the hornworm can grip and hold and move, in order to make robotic devices that move similarly. Already, he and his team have molded plastic models to simulate the caterpillars’ movements. With support from the National Science Foundation and the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, these caterpillars could very well be the nucleus of a whole new field of robotics.

A team of experts have written a detailed 300-page report on how to build an elevator to space. In a nutshell, to reduce the cost and energy of getting from Earth to space, a supertough, nearly 100,000-kilometer-long cable equipped with robotic “climbers” needs to be anchored near the equator. The researchers say current rocket technology used to get to space is not very practical because it spews chemicals into the atmosphere on liftoff, and it cannot carry much cargo. They conclude an elevator to the heavens makes more sense. The study was conducted under the auspices of the International Academy of Astronautics and benefited from review and comments by numerous members of the Academy, as well as the International Space Elevator Consortium.

Researchers describe oxygen’s different shapes

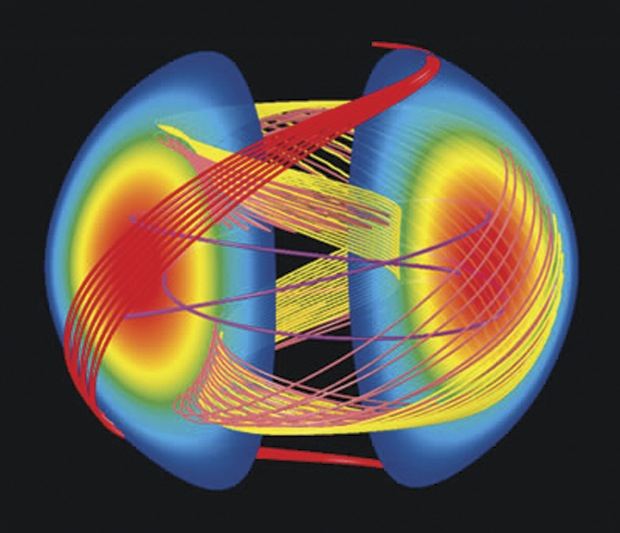

Oxygen-16, one of the key elements of life on earth, is produced by a series of reactions inside of red giant stars. Now a team of physicists, including one from North Carolina State University, has revealed how the element’s nuclear shape changes depending on its state, even though other attributes such as spin and parity don’t appear to differ. Their findings may shed light on how oxygen is produced. Carbon and oxygen are formed when helium burns inside of red giant stars. Carbon-12 forms when three helium-4 nuclei combine in a very specific way (called the triple alpha process), and oxygen-16 is the combination of a carbon-12 and another helium-4 nucleus. Using an approach called “effective field theory” they formulated a complex numerical lattice and found their lattice revealed that although both the ground and first excited states of oxygen-16 “look” the same in terms of spin and parity, they are quite different structurally.

Stanford engineers make flexible carbon nanotube circuits more reliable and efficient

In principle, CNTs should be ideal for making flexible electronic circuitry. These ultra-thin carbon filaments have the physical strength to take the wear and tear of bending and the electrical conductivity to perform any electronic task. Until this recent work from a Stanford University team, flexible CNT circuits did not have the reliability and power-efficiency of rigid silicon chips. The challenge was that CNTs are predominately P-type semiconductors and there was no easy way to dope these carbon filaments to add N-type characteristics. In a PNAS paper Stanford engineers explain how they overcame this challenge by treating CNTs with a chemical dopant they developed known as DMBI. They used an inkjet printer to deposit this substance in precise locations on the circuit. This marked the first time any flexible CNT circuit has been doped to create a P-N blend that can operate reliably despite power fluctuations and with low power consumption.

Acoustic cloaking device hides objects from sound

Using little more than a few perforated sheets of plastic and a staggering amount of number crunching, Duke engineers have demonstrated the world’s first three-dimensional acoustic cloak. The new device reroutes sound waves to create the impression that both the cloak and anything beneath it are not there. The acoustic cloaking device works in all three dimensions, no matter which direction the sound is coming from or where the observer is located, and holds potential for future applications such as sonar avoidance and architectural acoustics. The study appears online in Nature Materials.