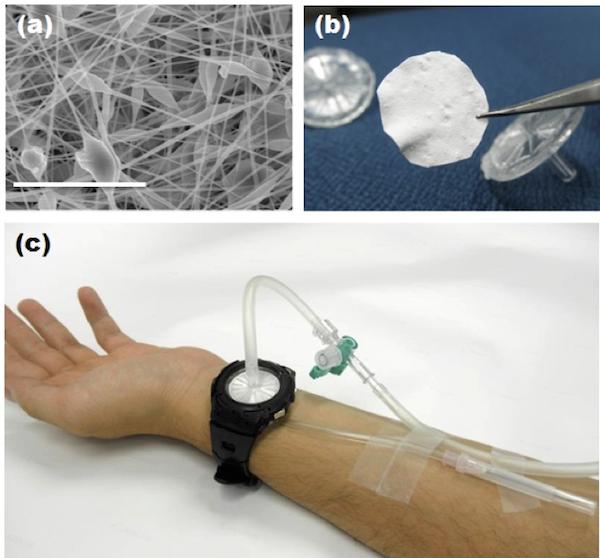

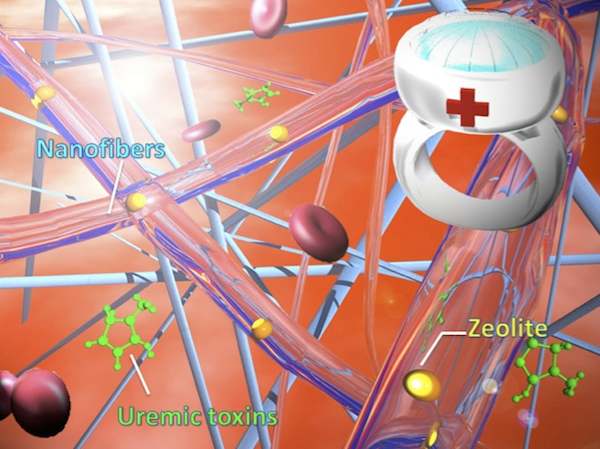

Japanese scientists have devised a simple wearable zeolite filter as an alternative to dialysis for kidney failure patients. (a) shows a micrograph of the material nanostructure; (b) shows a synthesized filter; and (c) shows how a simple wearable device could be fabricated, in this case from a hacked wristwatch. Credit: MANA.

Researchers from the International Center for Materials Nanoarchitectronics (MANA) at Japan’s National Institute for Materials Science have developed a simple and cheap mesh filter that could change the lives of kidney dialysis patients.

Kidneys are like the wastewater treatment plants for your body’s blood—they filter the good stuff from the bad, shunting wastes away and purifying the fluids that stay in circulation. Kidneys balance blood composition by regulating ion and chemical concentrations in the blood, remove waste products, and maintaining bodily water content, among other important functions. So when kidneys fail, it’s a big problem.

Patients with kidney failure must undergo dialysis, a medical procedure that uses a mechanical external kidney to perform the duties of a patient’s defunct organs. Blood must be pumped from the body, through the filtration machine, and then returned to the patient’s body, which means costly, repetitive, inconvenient, and invasive procedures are the norm for dialysis patients.

Areas without an established healthcare infrastructure also have trouble supporting dialysis patients, because they’re often unable to provide and maintain costly equipment and frequent procedures. This is also true of areas with interrupted healthcare services, such as after a major disaster (such as the Fukushima tsunami)—which is precisely what prompted the Japanese scientists to search for a dialysis alternative.

Their findings, published in Biomaterials Science, describe the synthesis of a dual-component filter composed of a matrix of polyethylene-co-vinyl alcohol (EVOH) nanofibers embedded with a mixture of zeolites, microporous aluminosilicates that can absorb uremic toxins (see images above). Embedded zeolites have decreased absorptivity from their free-ranging counterparts, but the authors describe in the paper’s abstract that their filter-incorporated zeolites still had 67% of the absorption of free zeolites.

According to the press release, the team “found that the silicon-aluminum ratio within the zeolites is critical to creatinine (a uremic toxin) adsorption. Beta type 940-HOA zeolite had the highest capacity for toxin adsorption, and shows potential for a final blood purification product.”

The scientists used electrospinning to synthesize the filters, making them cost-effective. Because the technology relies upon a simple filter device, dialysis patients could potentially ditch the dialysis center and dialysis machine, trading them in for a small wearable device.

“Although the new design is still in its early stages and not yet ready for production, (senior author) Ebara and his team are confident that a product based on their nanofiber mesh will soon be a feasible, compact and cheap alternative to dialysis for kidney failure patients across the world,” according to the press release.

The paper is “Fabrication of Zeolite–Polymer Composite Nanofibers for Removal of Uremic Toxins from Kidney Failure Patients” (DOI: 10.1039/C3BM60263J).