Newly developed flexible aerogels are 500 times stronger than earlier versions and can be used in everything from clothing insulation to building insulation.

A NASA scientist has just reported that the agency has devised major improvements in aerogel, a development that should speed its use in super-insulated clothing and shoes, higher capacity and efficiency refrigerators, building envelope insulation, heat shields and other products. The report was presented by Mary Ann B. Meador at a meeting of American Chemical Society.

Meador is part of a group working on aerogel at the NASA Glenn Research Center in Cleveland, Ohio.

Although “ordinary” silica aerogel is brittle, is is also very strong, as measured by high compressive strength in comparison to its mass. That is, it resists denting or crushing under load. Thus, it is eyeopening when Meador says, “The new aerogels are up to 500 times stronger than their silica counterparts. A thick piece actually can support the weight of a car.”

According to an ACS news release, the NASA group has devised two new types of aerogel.

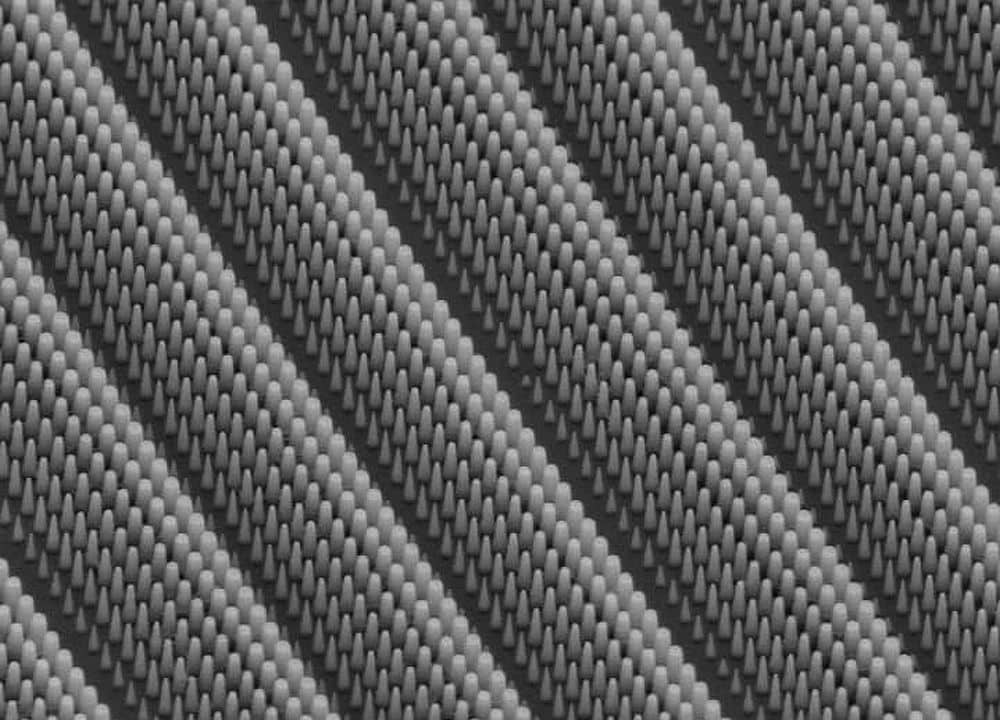

One involves making changes in the internal structure of traditional silica aerogels. They used a polymer, to reinforce the networks of silica that extend throughout an aerogel’s structure. Another involved making aerogels from polyimide, an incredibly strong and heat-resistant polymer, or plastic-like material, and then inserting brace-like cross-links to add further strength to the structure.

Heretofore, there have been several practical headaches for aerogel manufacturers, including the above-mentioned brittleness plus difficulties with forming shapes and finding suitable processing and installation methods. The holy grail quest has been to find a low-cost, easy-to-manufacture form of aerogel. Meador makes the remarkable observation that the new aerogels “can be produced in a thin form, a film so flexible that a wide variety of commercial and industrial uses are possible.”

We’ve written in the past how some aerogel has found its way into very limited lines of apparel, such as high-performance (and expensive) jackets atop Mt. Everest. Although I doubt today’s news means that Eddie Bauer or Patagonia will be offering a new aerogel line in time for the holidays, the descriptions of NASA aerogel do make it seem like it should be more conducive to garment assembly lines. Outdoor enthusiasts have other reasons to be happy: Meador also suggests that a new generation of insulated tents and sleeping bags should be attainable.

Building envelope applications are a natural for aerogel, and companies such as Thermoblok, Aspen and Cabot already have been working in these markets. Despite the production, handling and installation problems of silica aerogel, there has been some evidence that just using small strips of the material to prevent thermal bridging at target areas—such as wall studs—can be cost effective. So, cheaper and flexible aerogel strips would go a long way toward making the savings calculation easier. The housing stock in Europe, particularly Northern Europe, is particularly in need of improved insulation (no word yet on the results of the EU’s first Aerocoins aerogel workshop that was to be held this past June). Meador says that the new aerogel is five to 10 times more efficient than existing insulation, with a quarter-inch-thick sheet providing as much insulation as three inches of fiberglass. These insulation values are generally in line with ordinary silica aerogel, so the ease of use is the main thing here.

Meador doesn’t specifically mention it, but the ease of use factor would also be a big plus for the petroleum industry for pipeline insulation. She told me in an telephone interview that NASA has indeed been looking at several private sectors to license the new materials.

But, all of these are spin-off applications. NASA, of course, has a core interest in space, and Meador says the new aerogel may be suitable for improved spacesuit insulation and as a thermal barrier for advanced reentry systems. While the spacesuit application would seem to be relatively straightforward, the thermal barrier use is very novel. When it comes to efforts such as the International Space Station missions and Mars missions, rather than waste space with a thick and fixed heat shield, she says one concept is to store on the reentry vehicle something like a aerogel bag that can be inflated and deployed when needed.

Recently NASA posted a video (below) showing how such an inflated 10-foot-diameter shield could be packed into a 22-inch diameter nose cone, as part of the Inflatable Reentry Vehicle Experiment (IRVE-3) series of tests.

Credit: NASA Langley Research Center; YouTube

The inflation system was successfully tested July 21, 2012, while being deployed at 7,600 mph, and although the aerogel composition is not specifically mentioned in the news release about the test, Meador tells me that the outer layer of the shield was composed of pyrogel. She says new polyimide aerogel would be a desirable substitute for pyrogel because the latter creates significant dust release problems during the prelaunch handling and folding of the shield.

NASA has provided a brief description in a press release about the success of the test.

An inflation system pumped nitrogen into the IRVE-3 aeroshell until it expanded to a mushroom shape almost 10 feet in diameter. Then the aeroshell plummeted at hypersonic speeds through Earth’s atmosphere. Engineers in the Wallops control room watched as four onboard cameras confirmed the inflatable shield held its shape despite the force and high heat of reentry. Onboard instruments provided temperature and pressure data. Researchers will study that information to help develop future inflatable heat shield designs.

Check out NASA’s video of the launch and deployment here.

CTT Categories

- Aeronautics & Space

- Material Innovations

- Nanomaterials

- Thermal management

Related Posts

Sports-quality ice: From pond side to precision Olympic engineering

February 12, 2026