https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dQBwzmqMNDY

James Smith discusses PureMadi and MadiDrops—porous clay water purification systems—how they work and the hopes behind it. Credit: UVA, YouTube.

Access to potable water is a priority of the World Health Organization and UNICEF, and they address the issue through the Joint Monitoring Programme for Water Supply and Sanitation. In the Programme’s 2012 progress report (pdf) they report that they met their goal of reducing by half the number of people worldwide without access to safe drinking water and basic sanitation.

The very good news is that in the ten-year period from 1990-2000, over two billion people gained access to safe drinking water, so that by 89 percent, or 6.1 billion people worldwide now can get potable water for drinking and cooking. In fact, the United Nation’s Millennium Development Goal (Target 7) was to reduce by half the number of people without reliable, sustained access to safe water. According to the report, the goal was met five years ahead of the 2015 target date!

The accompanying bad news is that 11 percent, or 780 million people still need access to improved, pathogen-free drinking water. Few will be surprised to know that the scarcity hits harder in certain regions and populations. In the foreword, UN secretary-general, Ban Ki-moon, says,

Some regions, particularly sub-Saharan Africa, are lagging behind. Many rural dwellers and the poor often miss out on improvements to drinking water and sanitation. And the burden of poor water supply falls most heavily on girls and women. Reducing these disparities must be a priority.

In these regions where there is a dearth of infrastructure, simple solutions are especially attractive. And, it would appear, that the humble clay pot might be the answer to providing potable water, as well as some local industry.

An interdisciplinary team at the University of Virginia has developed a water purification system based on porous ceramic clay discs (“MadiDrops””— Madi is the Tshivenda South African word for water) impregnated with nanoparticles of either silver or copper. UVA professor James Smith from the department of civil and environment engineering explains in the idea in the video.

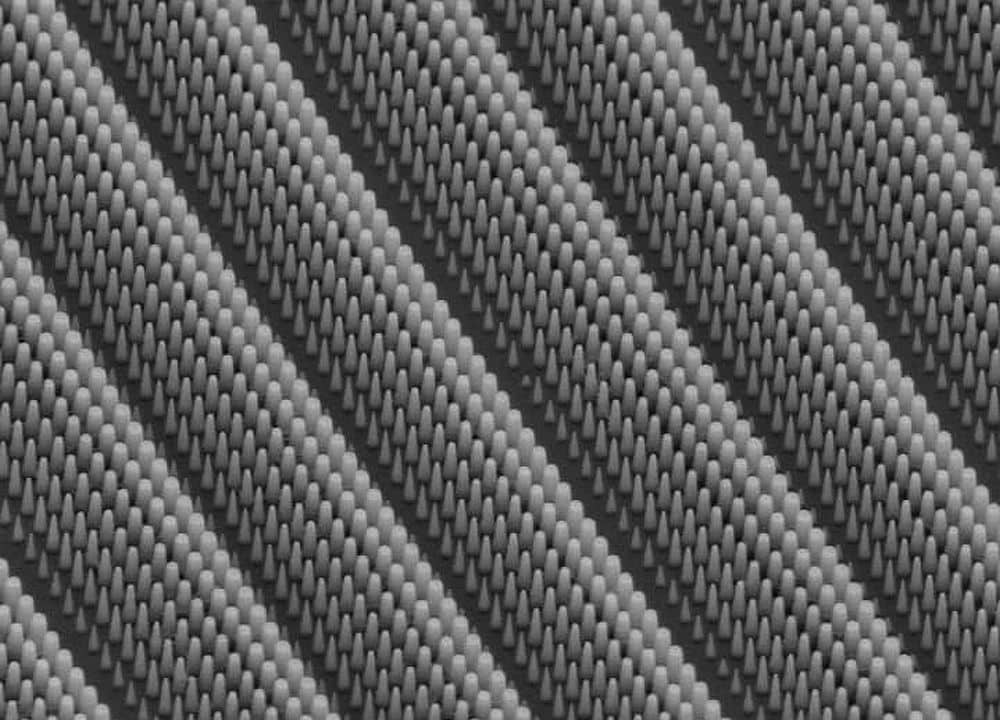

The press release describes the simple concept: Form porous ceramics by mixing and pressing indigenous clay with sawdust, which leaves behind a porous structure on firing. A nanoparticle slurry of silver or copper (both known to have anti-pathogenic qualities) is painted over the surface and impregnates into the pore structure. Water simply filters through and is purified as it passes over the silver or copper. The filters are made in either puck-like tablets or in flowerpot-like shapes. The flowerpot shape is set in a five gallon plastic bucket equipped with a spigot. The flow rate is one to three liters per hours, which is fast enough for drinking and cooking purposes.

The UVA team has established a nonprofit organization, called PureMadi, to set up factories and promote the technology.

PureMadi has set up a factory in Limpopo province, South Africa that has already produced several hundred flower-pot style filters. According to a UVA press release, PureMadi expects the plant, staffed mostly by women, to produce 500-1,000 filters per month. They hope to build another 10 to 12 plants in the next decade. Smith estimates that, based on these plans, the filters will provide potable water for up to 500,000 people per year. Smith says that tests show that the filter eliminates 99.9 percent of pathogens.

The MadiDrop is described as alternative to the larger pot filter, but they also can be used together. “MadiDrop is cheaper, easier to use, and is easier to transport than the PureMadi filter, but because it is placed into the water, rather than having the water filter through it, the MadiDrop is not effective for removing sediment in water that causes discoloration or flavor impairment,” Smith says. “But its ease of use, cost-effectiveness and simple manufacturing process should allow us to make it readily available to a substantial population of users, more so than the more expensive PureMadi filter.”

Smith notes that the MadiDrops can also be mass-produced at the PureMadi factories.

Author

Eileen De Guire

CTT Categories

- Biomaterials & Medical

- Environment

- Manufacturing

- Market Insights

- Nanomaterials