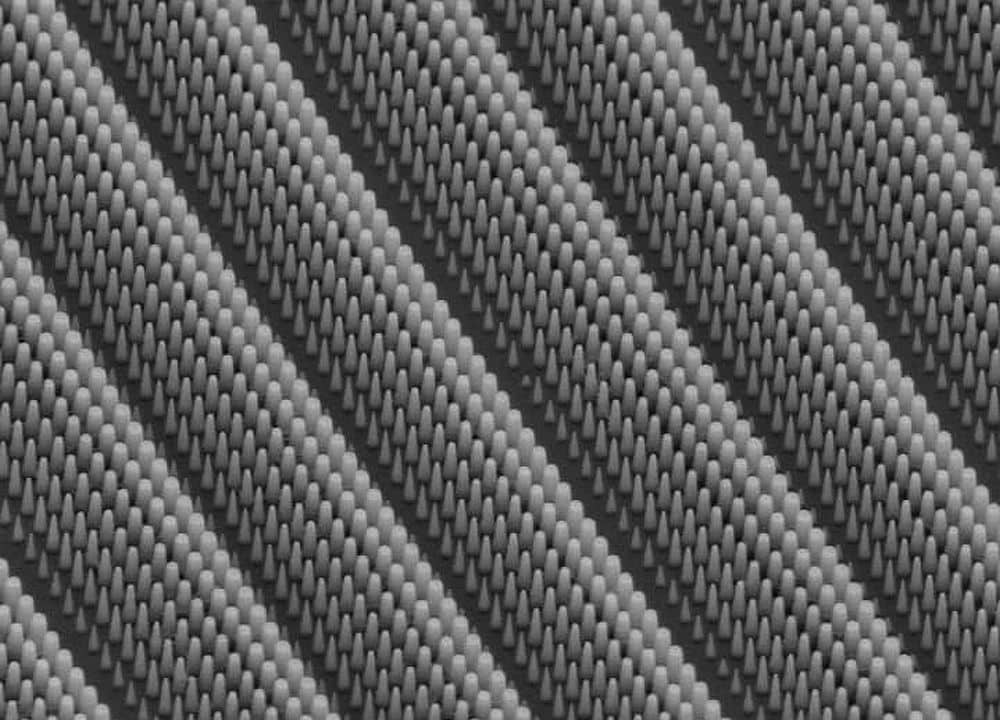

[Image above] Roman and Byzantine gilded clear glass tesserae were crushed and melted at Ribe in Denmark to create opaque white beads. Credit: Museum of Southwest Jutland

For archeologists, some of the most profound revelations concerning ancient cultures come from studying seemingly mundane objects.

Glass beads are one everyday artifact that provides rich insight into the Middle Ages. During this period, glass beads were popular as both jewelry and for trade. A tentative chronology of bead development by Matthew Delvaux, historian and Haarlow-Cotsen Postdoctoral Fellow in the Society of Fellows at Princeton University, illustrates the extensive role of glass beads in society during the Middle Ages.

- 660–700. Also called the Germanic Iron Age, Scandinavian elites distinguished themselves by showcasing exotic objects made from materials like glass and gold, which could not be obtained locally. They used these objects as votive deposits as well as being buried with them. Glass beads tended to be simple but made from high-quality blue, green, and white glass.

- 700–760. North Sea merchants partnered with Danish elites to establish a trading camp at Ribe, a coastal spot in southwest Jutland, Denmark. A companion market developed at Åhus in Sweden. Scandinavian craftspeople gained proficiency with glass, creating translucent blue beads decorated with red, white, and yellow rings.

- 760–790. Glass in Ribe and Åhus came from major production centers in the Near East, which prospered as the Islamic conquests put an end to the perennial conflicts between Byzantium and Persia. However, when the caliphate overextended, distant provinces revolted and a major coup interrupted the supply of new glass to Scandinavia, resulting in a network of smaller trading sites. Blue beads were replaced by thin “wasp” beads, which maximized length and minimized material. These beads were mainly black with yellow rings.

- 790–820. Bead imports renewed at Ribe and Åhus, and the loose network of small sites began to consolidate around a few urban nodes. Scandinavian glassworkers lacked the technology and expertise to blow glass, and so made beads by heating glass and wrapping it around a mandrel. Interestingly, the beads were rare at elite sites and cemeteries, which raises questions about what exactly they were used for.

- 820–860. Ribe and Åhus disappear from the archeological record; these trade centers may have moved elsewhere. Instead, places like Sebbersund and Hedeby became the major trading posts. A new style of drawn bead with tiny rings of blue, yellow, white, and black was found packaged with a handful of coins, suggesting these beads may have served a monetary function.

- 860–900. Another period of extreme disruption occurred in the Islamic world, slowing glass and silver imports. Meanwhile, Christianity took root in Scandinavian towns, and the new Christians did not bury their dead with grave goods. However, glass was in demand in the Danish archipelago, where a form of traditional Norse beliefs became popular. Here, people did bury their dead with grave goods, such as beaded necklaces.

In a recent paper, Danish researchers from Aarhus University and Museum of Southwest Jutland dug deeper into the history of these beads by analyzing glass samples from two different workshops at the Ribe trading site.

As noted in the timeline above, deterioration of long-distance exchange networks affected the ability of Scandinavian glassworkers to access new glass supplies. As such, analyses of glass products from the period indicate an abundant use of recycled materials.

Identifying where the recycled material came from “affords a material to untangle the complex network of interactions between processes and craft specialists across multiple sites, regions and stages of reworking,” the researchers write.

The samples selected for this study came from

- Early period workshop (700–720). Production at this site focused on monochrome blue and white beads in different shapes, with the addition of a few green monochrome beads and blue beads with red/white decorations. These color ranges correspond to the potential raw material present, namely vessel glass sherds, tesserae and chips/splinters, and waste material. (Tesserae are individual tiles used in creating a mosaic.)

- Late period workshop (760–790). Production focused on monochrome green or red cylindrical beads as well as on wasp beads with a black/dark cylindrical body and yellow applied bands. Compared to raw materials present at the Early workshop, tesserae were relatively rare while vessel glass sherds were relatively common. Green chips/splinters dominate, followed by blue and yellow splinters.

The researchers chipped small pieces from the beads, sherds, splinters, and tesserae for analysis, as well as from glassworking crucibles found at the site. Major elements were determined through electron microprobe analysis, while trace elements were determined using laser ablation inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry.

Additionally, the researchers used a multicollector inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometer to analyze hafnium isotopes, a technique which had only previously been used in archaeology in the study of sandstone artifacts.

“It was able to pinpoint the difference between glass coming from Egypt and glass coming from the eastern Mediterranean, which are the two places where the Romans and Byzantines were making this glass and that was the first time you could pinpoint it,” says Gry Hoffmann Barfod, lead author and administrative staff member in the Department of Geosciences at Aarhus University, in a History First article.

Analysis of the samples revealed no trace of the arrival of 8th-century glass types, such as Islamic plant ash glass. Instead, results indicated that the glass came from 4th-to-6th-century Roman and Byzantine mosaics. (The vessel glass sherds showed heavy contamination and were rarely used in the bead making.)

“This pattern of procurement is consistent with trends observed for nonferrous metalworking in Ribe’s emporium, which appear to reflect recycling within North Sea exchange, rather than an expansion of wider contacts beyond Northern Europe,” the researchers write in the paper.

Most surprisingly, the researchers discovered that while opaque white glass tesserae were available to the bead makers, they instead used clear glass tesserae to create the opaque white glass beads. Their fabrication process involved crushing the clear glass tesserae and melting them at a relatively low temperature, stirring to form tiny air bubbles resulting in the opaque white finish.

“This [bead maker] knowledge is almost like an alchemist’s. They really had chemical knowledge,” says Søren Sindbæk, senior author and professor of archeology at Aarhus University, in the History First article. “It is quite extraordinary that we find expertise in a faraway trading place that we wouldn’t be surprised if we had seen in Rome or Alexandria.”

The paper, published in Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences, is “Splinters to splendors: from upcycled glass to Viking beads at Ribe, Denmark” (DOI: 10.1007/s12520-022-01646-8).

Author

Laurel Sheppard

CTT Categories

- Art & Archaeology

- Glass