[Image above] Crystal structure of a new magenta pigment based on divalent chromium. Credit: Oregon State University

“Most pigments are discovered by chance,” says Mas Subramanian, the chemist who discovered the vivid pigment YInMn blue, in an Oregon State University press release.

Although our first encounter with chemistry may paint the field as a clear-cut case of action and reaction—I’m looking at you, baking soda volcano—knowing what a molecule or substance will look or act like is the exception, not the norm. Even with major advances in computer modeling and simulations, in many instances, developing new compounds remains a tedious trial-and-error process.

When Subramanian and his group discovered YInMn blue, they were investigating new materials for electronics when one of their samples turned a brilliant shade of blue. This accidental discovery became the newest blue pigment in more than two centuries.

“We got lucky the first time with YInMn blue,” Subramanian says. But now he and his team want to develop “some fundamental chemical and crystal structural design principles to rationally create new pigments,” he explains in the press release.

In a recent study, Subramanian, research associate Jun Li, and graduate student Anjali Verma describe a brand-new inorganic magenta pigment based on the divalent form of chromium, Cr2+.

Chromium exists in a series of oxidation states, with the highly toxic hexavalent state and low toxicity trivalent state commonly used in green and yellow pigments (see image below). Divalent chromium also has low toxicity, but it is relatively unstable and readily oxidizes to the trivalent state on Earth. However, it has been found in analysis of lunar mineral samples collected from the Apollo missions.

Credit: Compound Interest (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

Divalent chromium has the same number of unpaired electrons as trivalent manganese, the chromophore, or molecule, responsible for the intense color of YInMn blue. This structure suggests it may also be used to confer colors in materials.

To create a pigment using divalent chromium, Subramanian and his team used Egyptian blue as the basis for their design. Egyptian blue is one of the first known synthetic pigments discovered in Egypt more than 5,000 years ago. The chromophore in Egyptian blue is divalent copper, Cu2+, and the researchers aimed to replace this molecule with divalent chromium.

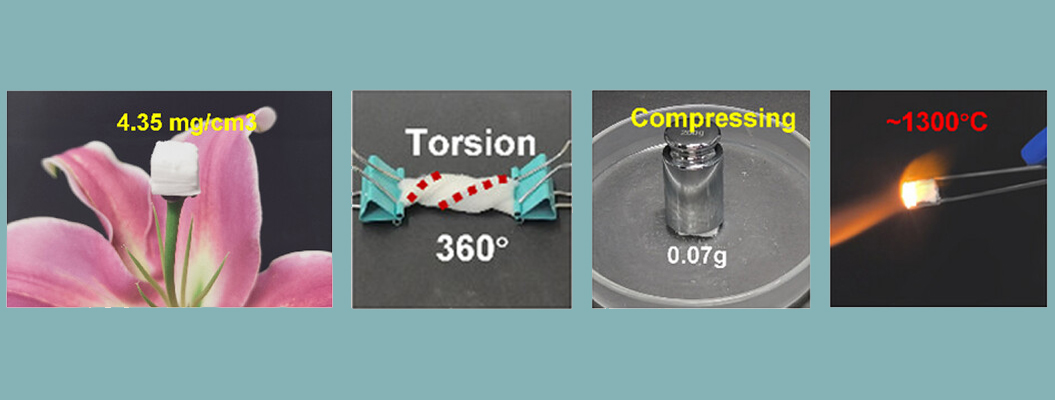

To stabilize the divalent chromium, the team prepared the pigment under high temperatures (~1371°C or ~2,500°F). The resulting divalent chromium-based magenta pigment has a similar crystal structure to gillespite, a rosy-red mineral described in previous research.

The new magenta pigment retained its color and chemical structure up to 500°C (932°F). It also survived intense acidic and basic environments without changes.

These findings are a significant improvement compared to current magenta-colored pigments. Most magenta-colored pigments are made from organic chemicals, and they suffer from stability issues when exposed to ultraviolet rays and heat. Some inorganic magenta pigments do exist, but most require cobalt salts, which are hazardous to both humans and the environment.

In addition to the color and structural stability of the divalent chromium-based pigment, the researchers found they could “tune” the hue of the magenta by adjusting the amount of magnesium in the compound (Ca1–xMgxCrSi4O10, with the value of x ranging from 0 to 0.2). The miscibility limit was 0.2, meaning that all values beyond that showed leftover unreacted materials.

Finally, the pigment also exhibited a high heat reflectance, reflecting approximately 70% of near-infrared light. This property means that the magenta has potential to be used as a “cool pigment” to help regulate vehicle or building temperatures, a concept known as solar control.

The magenta’s stability, tunability, and thermal properties suggest that divalent chromium could be a promising chromophore in a diversity of crystal structures, possibly producing a rainbow of new inorganic colors.

The paper, published in Chemistry of Materials, is “Cr2+ in square planar coordination: Durable and intense magenta pigments inspired by lunar mineralogy” (DOI: 10.1021/acs.chemmater.4c00253).

Author

Isabel Swafford

CTT Categories

- Art & Archaeology

- Material Innovations