According to a press release, researchers at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst have developed a “chemical nose” that can sniff out cancer. It’s a tool that could revolutionize cancer detection and treatment, according to chemist Vincent Rotello and cancer specialist Joseph Jerry.

An article describing the chemical nose method of cancer detection appears in the June 23 issue of the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences online.

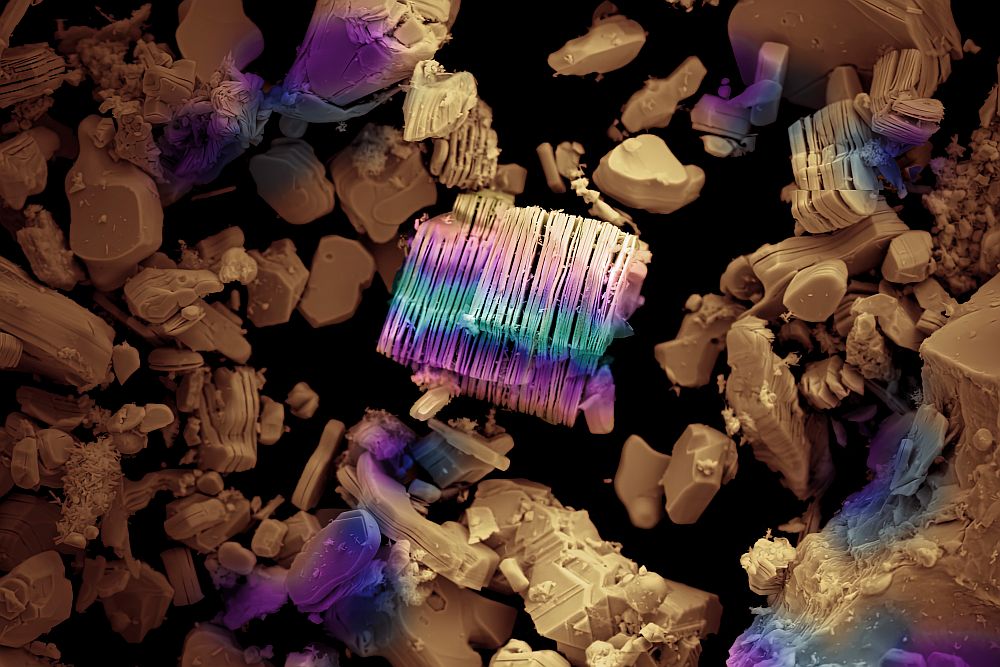

The tool contains an array of nanoparticles and polymers that differentiate between healthy and cancerous cells and also between metastatic and nonmetastatic cancer cells. According to the authors, their system is “based on a “chemical nose/tongue” approach that exploits subtle changes in the physicochemical nature of different cell surfaces.”

“Our new method uses an array of sensors to recognize not only known cancer types, but it signals that abnormal cells are present,” says Rotello. “That is, the chemical nose can simply tell us something isn’t right, like a ‘check engine light,’ though it may never have encountered that type before,” he added.

Further, the chemical nose can be designed to alert doctors of the most invasive cancer types, those for which early treatment is crucial.

The study conducted using four human cancer cell lines (cervical, liver, testis and breast), as well as in three metastatic breast cell lines, and in normal cells showed that the new detection technique correctly indicated not only the presence of cancer cells in a sample but also identified primary cancer versus metastatic disease.

In further experiments to rule out the possibility that the chemical nose had simply detected individual differences in cells from different donors, the researchers repeated the experiments in skin cells from three groups of cloned mice: healthy animals, those with primary cancer and those with metastatic disease. Once again, it worked. “ This result is key,” says Rotello. “It shows that we can differentiate between the the three cell types in a single individual using the chemical nose approach.”

Rotello’s research team, with colleagues at the Georgia Institute of Technology, designed the new detection system by combining three gold nanoparticles that have special affinity for the surface of chemically abnormal cells, plus a polymer known as PPE, or poly-para-phenylene-ethynylene.

As the “check engine light,” PPE fluoresces when displaced from the nanoparticle surface.

CTT Categories

- Biomaterials & Medical

- Material Innovations

- Nanomaterials