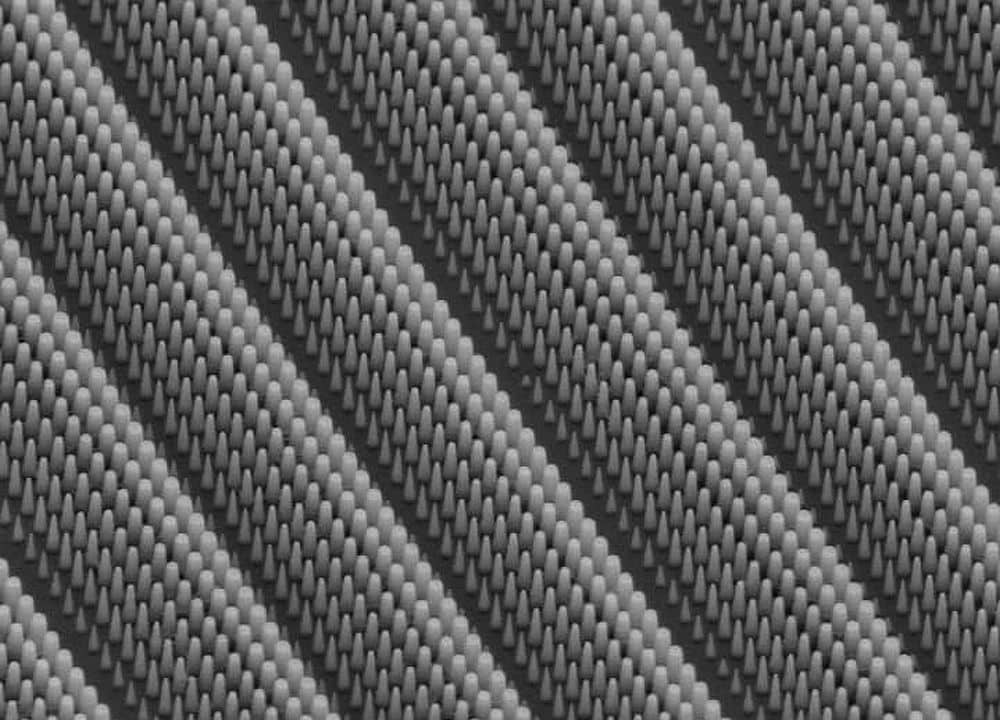

[Image above] Our world of windows poses a threat to birds, who often cannot distinguish clear glass from ongoing air—but, ceramic frit glass can help. Credit: DuPont

We’ve all seen it happen or (unfortunately) been there ourselves—what you think to be a perfectly open doorway turns out to have a pane of glass hiding in its embrace. If you haven’t seen it happen or been there yourself—or if you just enjoy some timeless physical comedy—try stifling a laugh while watching this:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wqBJk_88yaU

Credit: Urlesque; Youtube

Because glass lets those sneaky photons pass through, it’s easy to forget it’s there. And we’re not the only creatures to be fooled—bird advocacy groups estimate that hundreds of millions of birds die every year from bird-on-glass collisions in the U.S. alone, towering over the number of collisions with power lines, towers, and wind turbines combined.

Just imagine, for a moment, that you’re a bird—you’re cruising along the blue sky at about 30 mph (ten times the average human walking pace of just 3 mph), gazing ahead at more shiny blue sky, when—SPLAT.

This dead woodpecker was found at the base of a mostly-glass-sided building on Ohio State University’s medical center campus. Credit: T. Gocha

Highly reflective windows, flat facades, and indoor atriums pose some of the biggest hazards to airborne birds. The birds simply can’t see them well enough to distinguish their shine, reflection, or deception to steer clear. Brightly lit buildings at night also pose a big problem, especially to migratory birds, spurring organizations like the Fatal Light Awareness Program (FLAP) to vie for tall urban building inhabitants to go dark post-workday.

To a bird, the many windows and reflections of a city (here, Toronto) are really confusing. Credit: Kat N.L.M.; Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0

Because birds are important parts of our ecosystems through their roles as pollinators, seed spreaders, pest controllers, cleanup crews, and more (and because we can always strive to be better Earth inhabitants), scientists are actively researching how to better protect birds from glass collisions.

[And because science and art are inexorably intertwined, building-enhanced avian death even inspired artist Cai Guo-Qiang’s 2006 sculpture installation, titled “Transparent Monument” (right), on the roof of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. The installation featured a large transparent pane of glass reaching into the sky, with several faux—albeit very realistic—dead birds lying at its base.]

One solution to make glass safer for airborne creatures is to make it more visible to them by incorporating lines, dots, or other visible patterns into the glass. When it comes to lines, previous research shows that they most effectively divert birds when spaced two inches apart for horizontal rows or four inches apart for vertical rows (referred to as the “2×4 rule”). Less is understood about how birds see other patterns.

Just how do we know what birds can see? Researchers use flight tunnel experiments to test what materials and innovations birds avoid best in comparison to standard transparent windows. The researchers catch wild birds and introduce them to dark tunnels affixed with two distant window panels, one standard window next to an experimental window. The bird is released, and the scientists monitor which window the bird flies towards (don’t worry—the windows are preceded by a fine mesh to protect the birds from actually smacking into the test panels). This process is repeated over and over again with many different individuals and types of birds. These experiments help determine which strategies work best to maximize window visibility to birds, ultimately protecting them from transparent manmade dangers. (Check out the stories at NY Times and NPR for more about the research.)

Simple decals can help birds distinguish see-through surfaces, although decals are not permanent and can be difficult to implement on large structures with a lot of glass. As an alternative, permanent patterns can be applied to glass with ceramic frit—the frit can be silk-screened on the glass, so that virtually any design can be incorporated. Although frit glass is usually installed to afford privacy or increase energy efficiency (by decreasing solar heat gain), frit can also make glass more visible to birds.

According to the website for Oldcastle Building Envelope, a building company that supplies frit glass, “Ceramic enamel frits contain finely ground glass mixed with inorganic pigments to produce a desired color. The coated glass is then heated to about 1,150°F, fusing the frit to the glass surface, which produces a ceramic coating almost as hard and tough as the glass itself.”

Patterns can also be acid-etched onto the glass, as is done by Walker Glass for their AviProtek line. According to their website, AviProtek is “one of the most effective bird safe glazing solutions on the market today.” The glass is sold in a variety of lined patterns or can be acid-etched across the whole surface for a frosted look, all of which help birds distinguish the glass’s presence.

However, many architects, builders, and inhabitants simply don’t want anything—dots, lines, patterns, decals, or frosting—obstructing their clear view. So clear, naked glass use continues to increase in modern architecture, especially with the growing popularity of environmentally certified buildings, which favor glass building materials.

A particularly good way to make glass highly visible to birds, while remaining transparent to the human eye, is to incorporate ultraviolet (UV)-reflective patterns into the glass. Birds see the world differently than we do because they, along with some other creatures, have four types of photoreceptive cones in their eyes. We human creatures have only three that provide us with vision in the visible region of the light spectrum—that extra type of cone allows bird vision to range into the UV portion of the spectrum.

German glass company Arnold Glas makes a special line of “bird protection glass,” called Ornilux (first written about by ACerS editor Peter Wray back in 2010), that incorporates UV designs directly into the glass. Inspired by spiderwebs, some of which incorporate UV-reflective silk strands, the glass is embedded with UV patterns that birds can see. Because we only have three cone types, however, the glass appears clear to us. (What else is present in the “invisible world” that you can’t see? Check out this short video to see.)

Arnold Glas marketed its first Ornilux UV bird protection glass, which contained only vertical lines, in 2006. In 2009, the company introduced an improved glass, Ornilux Mikado, that features criss-crossed patterns resembling pick-up sticks (the German word for which is mikado). Mikado offers better visibility to birds and improved invisibility to humans over the initial product.

Mikado’s patterns are applied with a patented UV-reflective coating that is highly visible to birds. According to the Ornilux case report (pdf), “The researchers found that a patterned coating (versus a solid coating) made the contrast of the glazing more intense: the coated parts reflected UV light while the interlayer sandwiched between two layers of glass absorbed the UV light. The two functions together enhanced the reflective effect. Although the specific pattern of a spider’s web inspired the solution, the team had to design a unique pattern for the window coating in order to make the application process practical.”

Ornilux’s website states that Mikado received tunnel scores (the percentage of birds that avoided the glass) between 61–77 in testing by the American Bird Conservancy. The NY Times also reports that testing conducted at the Bronx Zoo, although still ongoing, shows some preliminary results that are promising for UV-patterned glass, with two thirds of birds navigating away from it. Black fritted horizontal lines also fared pretty well in those tests. To see a short video of what the testing looks like, head over here.

Although glass continues to be a favored building material, these advances are helping protect birds in our urban jungles. The U.S Green Building Council, which dishes out LEED ratings, even now includes a bird-safety credit as part of the certification process. To read more about bird-friendly building design, click here for a pdf from the American Bird Conservancy or download this one from the New York City Audubon Society.

Author

April Gocha

CTT Categories

- Biomaterials & Medical

- Environment

- Glass

- Material Innovations

Related Posts

Sports-quality ice: From pond side to precision Olympic engineering

February 12, 2026