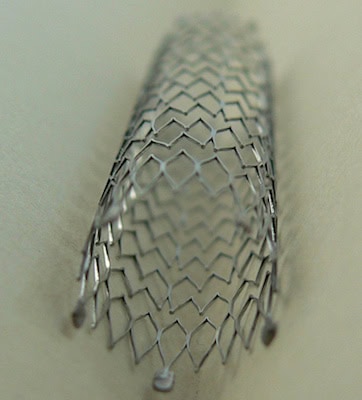

A bare-metal coronary stent. Credit: Frank C. Müller; Wikipedia Creative Commons license

The 2010 Affordable Health Care Act includes a provision for a 2.3% excise tax to be levied against the revenues of medical device companies starting in 2013 regardless of whether the company generates a profit or not, which means companies could owe more in tax than they generate in profit. The tax is expected to generate $20 billion between 2013 and 2019. The tax revenues are part of a multi-industry excise tax plan to pay for health care coverage for the uninsured, according to a CCH Tax Briefing. Pharmaceutical and insurance companies are also being levied.

In mid-July, a coalition of over 400 medical device companies sent letters to House and Senate leadership urging the repeal of the legislation. The industry fears that the tax will cripple its ability to be innovative.

In the letter, the industry notes that it employs over 400,000 workers in the US with higher than average salaries ($58,000 vs. $42,000) and invests close to $10B in research and development annually. The industry has a few big players like Stryker, Medtronic and Boston Scientific, but this is largely a start-up and small business industry with over 80 percent of medical device companies employing fewer than 50 employees. Only two percent employ more than 500.

The signatories to the letter argue that the tax will slow innovation and cost jobs by raising the effective tax rate on the companies and soak up cash that is used for R&D, clinical trials and manufacturing and that the “impact will be especially hard on smaller companies whose innovations are not immediately profitable.”

They also contend that health care costs will increase as the tax is passed to consumers and that there won’t be a “windfall” of increased demand for the for medical devices to offset the tax. The letter states, “Unlike other industries that may benefit from expanded coverage, the majority of device-intensive medical procedures are performed on patients that are older and already have private insurance or Medicare coverage.” In the case of Medicare (and Medicaid) patients, reimbursement rates are set by the government and do not cover costs like administration or shipping. Manufacturers are not expecting adjustments to the government reimbursement rates to accommodate the excise tax, according to an article from The Berkshire Eagle.

A bill was introduced last summer by Congressman Brian Bilbray to repeal the tax legislation. It must not have gotten too far because Senator Orin Hatch and Congressman Erik Paulsen also introduced a repeal bill in January of this year.

Meanwhile, the Center for Public Integrity reports that the industry has asked the IRS to weigh in regarding what exactly a medical device is. It is clear that consumer devices like eyeglasses, contact lenses, hearing aids and “any device the Treasury Department determines is generally purchased by the general public at retail for individual use” are exempt. Less clear is whether durable medical equipment like wheelchairs, prosthetics and orthotics will be subject to the tax. While the industry appears to be presenting a unified front to Congress, the CPI report indicates that the industry is splintered in its approach to the IRS, each segment lobbying to protect its niche.

The CPI article also raises the issue of a “tax deduction windfall,” where a manufacturer could conceivably pass the excise tax cost to the customer, then take a write-off for the “tax paid.” Clearly another issue requiring IRS guidance.

In a related development, the Institute of Medicine released a report in July on the “Public Health Effectiveness of the FDA 510(k) Clearance Process,” the process by which medical devices and their next-generations are approved. Congressional Democrats commissioned the study to determine whether “the industry needed tougher regulations to ensure the safety and effectiveness of its products.” Some are of the opinion that better regulation processes could have a major impact on health care spending. Next-gen devices, for example, are subject to little or no clinical testing for approval, which can lead to a higher recall rate or “improvement upcharges” that do not necessarily correlate to improved outcomes.

Author

Eileen De Guire

CTT Categories

- Biomaterials & Medical

- Manufacturing

- Market Insights