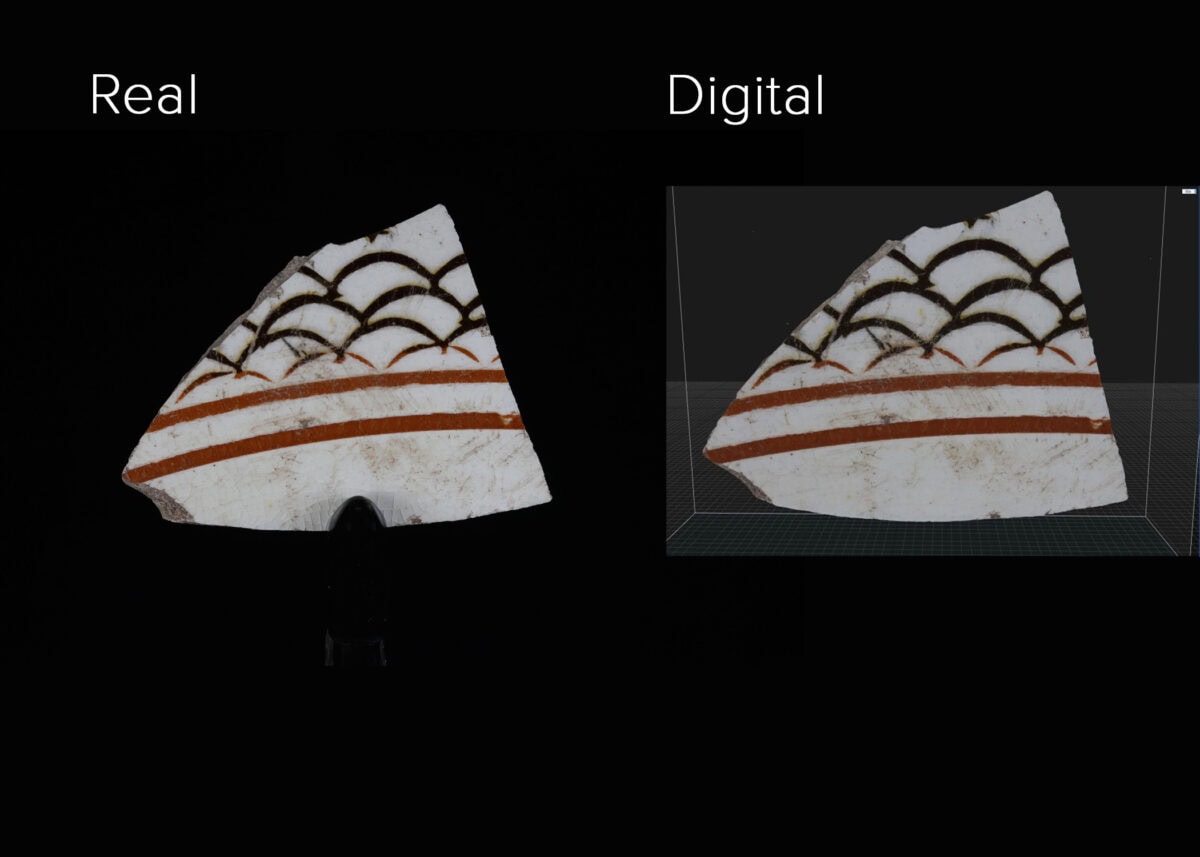

[Image above] Side-by-side comparison of a ceramic sherd and its digital counterpart. Credit: SCDNR Cultural Heritage Trust Program

As professional archaeologists well know, there are various features that can be used to identify what object a ceramic sherd came from during digs, including the color, texture, and shape of the piece. Now students and other researchers can sharpen their ability to identify these features in both field and laboratory settings thanks to the new Ceramic Digital Type Collection created by the archaeology team at the South Carolina Department of Natural Resources’ (SCDNR) Cultural Heritage Trust Program.

The digital collection is based on the Program’s physical collection, which consists of artifacts discovered on SCDNR properties. The idea for this collection came from master’s student and former team member, Jacob Hamill, who was studying for his ceramics typology exam using detailed, handmade paper flashcards. Two Heritage Trust Program team members, Gabe Donofrio and Charles Scarborough, both Public Outreach Archaeologists and specialists in photogrammetry, then executed the idea to digitize the physical pieces into 3D objects.

“The foundation for the digitization was laid by earlier SCDNR Heritage Trust Program projects and team members,” says Scarborough in an email. Adds Donofrio, “it builds on several iterations of internal projects the Heritage Trust Program team has worked on in the past.”

With the help of other team members, the dynamic duo first had to identify well-preserved and representative examples of different ceramic types from the physical collection.

“The SCDNR Heritage Trust Program curation includes type collection cabinets,” explains Donofrio. “Those cabinets house many of the ceramics featured in the Sketchfab collection, and so it was a quick and easy process to access different ceramic types.”

Then Donofrio and Scarborough developed the digitization process, which relies on photogrammetry, a technology that extracts geometric information from 2D images to generate 3D models of objects. The steps of the digitization process are

- The object is set up on a turntable so it can be rotated to take photos of all sides. A scale bar is placed alongside the object, which allows precise scaling of the object in the software.

- Multiple photos of the artifact are taken at several different angles.

- The photos are input into one of two software programs, RealityScan or Agisoft Metashape, to produce point clouds, or a rough representation of the scanned object. Scarborough says that RealityScan is faster at producing the clouds and usually leads to higher detail in the final model than Agisoft, but Agisoft allows for more control over the process if the points are not going together smoothly.

- The point cloud is used to make a solid untextured model that includes all the surface details seen on the real object.

- The final step is texturing, which creates a finished colored model that resembles the real object.

Recent improvements to the process include color correction and a new camera that enables focus stacking, which allows images of the object at different focal depths. These images are then combined into a single sharp image where the entire object is in focus. Fine surface details are revealed that otherwise might be lost with just a shallow depth of field.

Each model is uploaded to the web platform Sketchfab, and after consultation with other team members, annotations and descriptions with contextual data such as ceramic type, time period, and other notable features are added.

“We focused on providing clear, general descriptions that are useful for a wide range of people [so that] the collection is approachable and readable, especially for students, interns, or anyone just beginning in ceramics or archaeology,” explains Scarborough.

The collection, which became available in July 2025, is housed on the Heritage Trust Program’s Sketchfab page and received more than 700 views since it was uploaded.

“We expect usage to grow as we continue to develop the collection and incorporate it more directly with our interns for use in artifact identification,” Scarborough says.

SCDNR is not the only digital ceramic collection. Others include

- Digital Archaeological Archive of Comparative Slavery (DAACS)

- Florida Museum of Natural History (Digital Ceramic Type Collection – Historical Archaeology)

- The University of North Carolina Research Labs of Archaeology (3D model collections by RLA Archaeology)

So what makes SCNDR’s digital collection different? The digitization team attempts to reproduce the physicality of the object on the model with detailed surface textures, geometry, gloss variation, and reflections.

“If we do this accurately,” Donofrio explains, “there are differences in gloss types that can be communicated through the 3D model, which wouldn’t otherwise be possible to view in a photograph or description.”

Meg Gaillard, Heritage Trust Archaeologist in charge of the digitization team, also believes their collection is unique because it is used for public engagement in a multifaceted way.

“One example is the in-production children’s book Fort Frederick: A SCDNR Heritage Preserve and the World It Changed by Reece Spradley, in which artifacts illustrated in the book link to 3D models. These models can be 3D printed and showed to school kids on a tour of the site or within a classroom setting,” she says.

The book is currently in the development stage, and Gaillard says they hope to test it in schools and on public tours at properties in 2026. She adds that The Heritage Trust Program hopes to produce a children’s book for each of their 19 Cultural Heritage Preserves.

Next steps

Plans are underway to add new ceramic types while also filling gaps in existing categories.

“Within our collection we have many different categories of sherds,” says Scarborough. “There can be variation within those categories, and we would like to have models for those as well. For example, we have three different models of whiteware, the whiteware sherd, edge molded whiteware, and transfer print whiteware. We do this to be as thorough as possible and try our best to cover the major types and subtypes of ceramics people may find.”

Additionally, “We want to expand the collection while ensuring that we are providing accurate information, which takes time to do well,” says Donofrio. “We also want to develop a more holistic system for contextualizing these 3D models as we produce them to ensure that the information we gather in this process remains with the model itself.”

Specifically, the team plans to integrate all the provenance data (when and where the artifact was excavated) into their 3D production pipeline. In other words, the context of the object will not be separated from the digital files during the scanning process.

“Eventually, we hope the collection can become a go-to reference for education, identification, and general public engagement for the Heritage Trust Program’s collections,” says Scarborough.

Author

Laurel Sheppard

CTT Categories

- Art & Archaeology

- Education

Related Posts

Sports-quality ice: From pond side to precision Olympic engineering

February 12, 2026