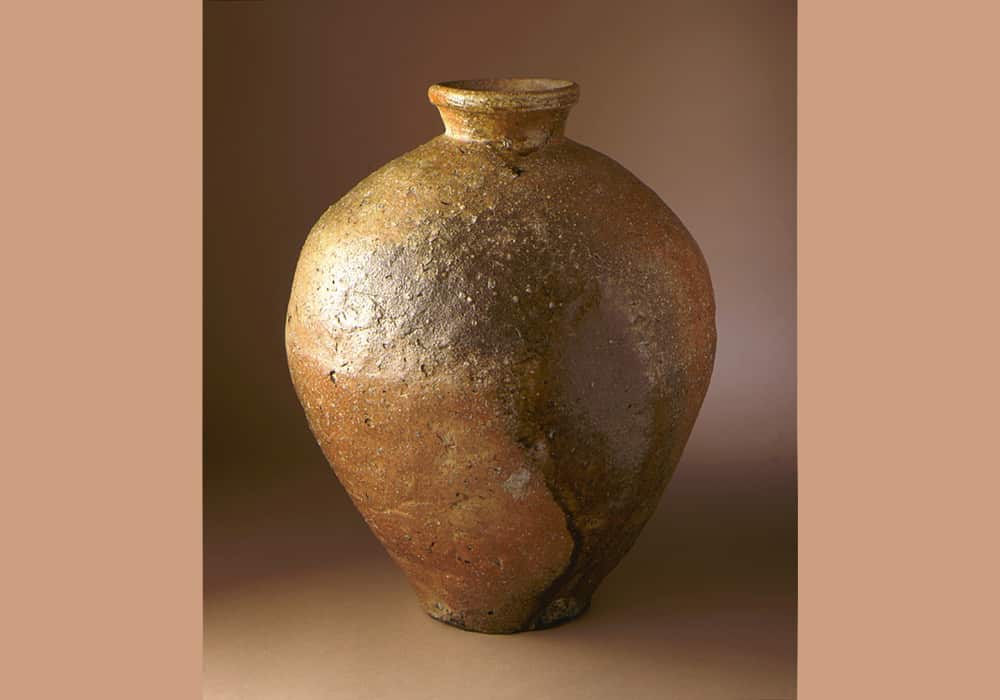

[Image above] Example of a Shigaraki ware piece from the Muromachi period (early 15th century). Credit: Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Wikimedia (Public domain)

Today, Japan and the United States share a strong relationship, cooperating closely in numerous foreign policy areas, particularly security and trade.

However, during the early 20th century, Japanese–U.S. diplomatic relations soured, and the two countries ended up fighting on opposing sides during World War II.

With such a fraught history, how did these two world powers repair their relationship and become so close today? While the answer to that question involves many, many entwined and complex factors, a new exhibition at the University of Michigan Museum of Art provides a look at one very small (possible) piece of the puzzle.

The exhibition, titled “Clay as Soft Power: Shigaraki Ware in Postwar America and Japan,” examines how Shigaraki ware may have helped transform the U.S. public’s image of Japan.

A brief history of Shigaraki ware

Shigaraki ware is a type of stoneware pottery produced in the town of Shigaraki in Kōka District, Shiga Prefecture, Japan. It is considered one of Japan’s Six Ancient Kilns, or ceramic production sites in Japan with long histories that are the foundation of the country’s domestic ceramics industry.

Shigaraki ware is known for its coarse and complex texture, which results from the use of unsieved clay and through chemical reactions during the firing process.

Shigaraki ware first developed in the 13th century as storage and cooking vessels for nearby farming communities. However, the rusticity of Shigaraki ware became a prized look by tea masters, and Shigaraki ware became a key part of the tea ceremony during the Muromachi (1338–1573) and Momoyama periods (1573–1603).

During the Edo period (1603–1867), a commercial infrastructure for pottery production developed, and Shigaraki ware began to be produced in mass quantities, including in the form of daily utensils such as plum jars, miso jars, sake bottles, and flameware.

Today, the most iconic product in this style of pottery are sculptures of the Japanese tanuki, or raccoon dog, which symbolize good luck and fortune.

Shigaraki tanuki, as seen in this picture from Shigaraki Toen Tanuki Village, come in all sizes. Credit: jpellgen (@1179_jp), Flickr (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

The (possible) role of Shigaraki ware in mending postwar Japanese–U.S. relations

Prior to World War II, the contemporary Japanese ceramics known to people in the U.S. were the delicate, elegantly decorated porcelain wares made for export. However, these pieces projected imperial splendor rather than inviting personal connection.

In contrast, Shigaraki ware appeared as the rustic pottery of a humble people. As such, pieces in this ceramic style were more suited to portraying Japan as a peaceful, democratic ally.

From the 1960s to 1980s, Shigaraki ware entered U.S. public and private collections and became a staple in permanent galleries and presentations of Japanese art. At the same time, support from government agencies, universities, and foundations funded U.S. ceramic artists to travel and study at traditional kiln sites in Japan; many chose to go to Shigaraki.

While how much influence Shigaraki ware played in strengthening Japanese–U.S. relations cannot be known, the exchange of artists had a quantifiable impact on subsequent Shigaraki traditions. For example, as stated in a Forbes article, Japanese ceramicists became more accepting of female ceramicists upon exposure to accomplished U.S. women.

‘Clay as Soft Power’ at UMMA

On Nov. 12, 2022, the “Clay as Soft Power” exhibition opened at the University of Michigan Museum of Art. The exhibition, which consists of more than 50 Shigaraki works, focuses mostly on yakishime pieces, i.e., unglazed, wood-fired wares. The pieces come from the Museum’s collection as well as loans from public and private collections in the U.S. and Japan. They will remain on display until May 7, 2023.

In December 2022, the Japanese Art Society of America hosted a lecture by Natsu Oyobe, curator of Asian Art at the University of Michigan Museum of Art, on the new “Clay as Soft Power” exhibition. View the lecture below.

Credit: JASA: Japanese Art Society of America, YouTube

Author

Lisa McDonald

CTT Categories

- Art & Archaeology