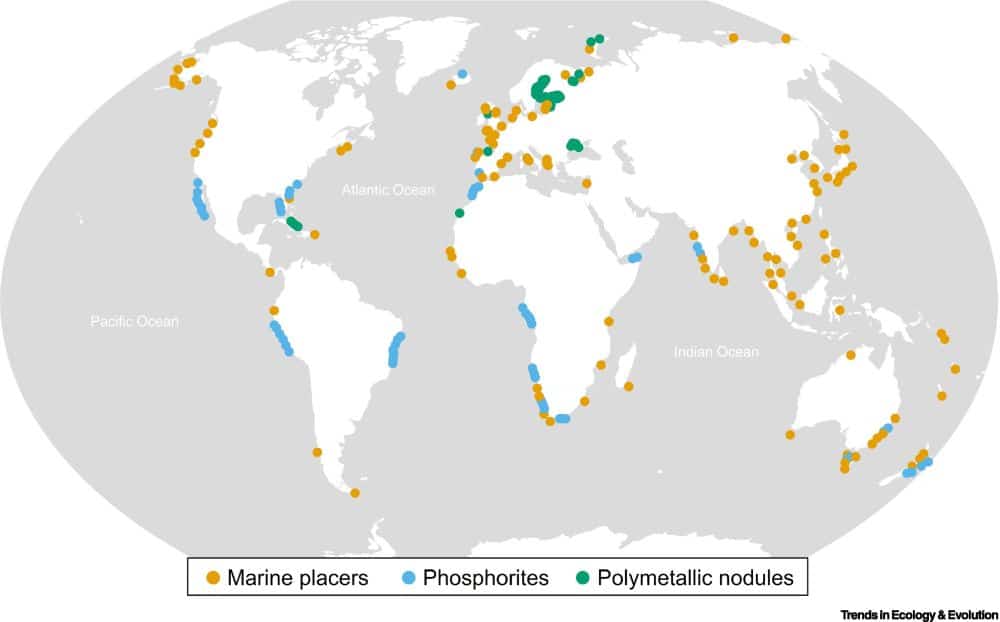

[Image above] Overview of the currently known main marine mineral resources (marine placers, phosphorites, and polymetallic nodules) on the continental shelf, which have extraction potential defined by their proximity to the coast and depth of the resource. Credit: Kaikkonen and Virtanen, Trends in Ecology & Evolution (CC BY 4.0)

As highlighted on CTT last week, we must proceed with caution when considering alterations to the environment. That warning is especially relevant to the mining industry in light of the recent approval of an industrial seafloor mining trial.

Because of the environmental and economic concerns associated with mining mineral deposits on the deep seabed, some companies and countries are considering shallow-water mining instead.

Unlike deep-sea mining, which is defined as mining the seabed at ocean depths greater than 656 feet (200 meters), shallow-water mining is not strictly defined by depth but rather by location. It usually refers to operations that occur on the continental shelf with easier access to the coast.

Proponents of shallow-water mining argue that, in addition to being more accessible than deep seabeds, better knowledge of shallow-water ecosystems and their shorter recovery times makes mining these areas less environmentally and economically risky.

However, a recent open-access paper raises concerns about viewing shallow-water mining as an eco-alternative to deep-sea mining.

The Finland-based authors are Laura Kaikkonen from the University of Helsinki and Baltic Marine Environment Protection Commission and Elina A. Virtanen from the Marine Research Centre at the Finnish Environment Institute.

In their paper, they show how the arguments given above for shallow-water mining rely on scant critical evaluation. Yet numerous shallow-water mining projects are already taking place because, unlike the stringent regulations for deep-sea exploration and exploitation coordinated by the intergovernmental International Seabed Authority, coastal areas often fall under the jurisdiction of national legislatures.

Take Indonesia, for example. Indonesia is the world’s largest exporter of tin and second largest producer of the metal, behind China. As land-based tin resources dwindled, Indonesia turned to dredging tin off the coast of the Bangka-Belitung Islands.

The huge expansion of shallow-water mining operations has heightened tension with fishermen, who say their catches have collapsed due to steady encroachment on their fishing grounds since 2014.

“We used to get at least 10 kilograms in a day. Now, only two kilograms, and sometimes we come back with nothing because the location has been destroyed by an illegal mining site,” a fisherman tells Reuters in an interview.

The evidence of mining’s coastal effects is not just anecdotal. Conservation news site Mongabay reports that the Indonesian Forum for the Environment found tin mining in Bangka has degraded 5,270 hectares (13,022 acres) of coral reef and 400 hectares (988 acres) of mangrove forest.

Credit: Reuters, YouTube

“Considering the absence of environmental regulation and risks to marine biodiversity, shallow-water mining is not a low-risk solution to overcome the environmental and ethical issues of mining on land and in the deep sea,” Kaikkonen and Virtanen write. Thus, “precautionary conservation measures and systematic comparisons of alternative ways to obtain the required minerals must be taken before seabed mining, be it in the shallow water or in the deep sea, is allowed to proceed.”

The open-access paper, published in Trends in Ecology & Evolution, is “Shallow-water mining undermines global sustainability goals” (DOI: 10.1016/j.tree.2022.08.001).

Author

Lisa McDonald

CTT Categories

- Education

- Environment