[Image above] American musician and historic preservationist Dennis James plays a glass armonica that he created based on Benjamin Franklin’s original design. Credit: Ars Lyrica Houston, YouTube

As the lighting designer for my high school’s stage crew, I witnessed the whole gamut of musical abilities, from elementary school vocal concerts to experienced touring musicians. These experiences helped me appreciate how different a single instrument can sound when it’s in the hands of a beginner versus seasoned professional.

Since then, my interest in music expanded to consider the role materials play in an instrument’s sound as well as the musician’s skill. This role is most apparent when instruments are made from materials not typically used for that purpose, such as glass guitars and concrete trumpets.

Though ceramic and glass materials are uncommon in mainstream instruments, there are instruments that are meant to be made from these materials.

For example, ocarinas and xuns (lesser-known sister instruments from China) are traditionally made from clay. The video below compares the sound of these two wind instruments.

Credit: Ashley Jarmack, YouTube

Glass is used even less frequently, with the glass harp—i.e., an array of upright wine glasses played by running moistened or chalked fingers around the rim—being the one example most people recognize.

Credit: GlassDuo – Glass Harp, YouTube

What few people know, though, is that the glass harp inspired the creation of yet another glass instrument, which was designed by one of the most well-known inventors in the United States.

Benjamin Franklin’s glass armonica

In the mid-1700s, American polymath Benjamin Franklin served as a delegate for the colonial U.S. As a delegate, he spent a great deal of time traveling to London and Paris.

During this period, glass harps were a popular instrument among amateur musicians. Franklin heard this instrument when attending a performance by English scholar and linguist Edward Delaval. Intrigued by the glass harp’s sound, Franklin started exploring how he might improve the instrument’s design.

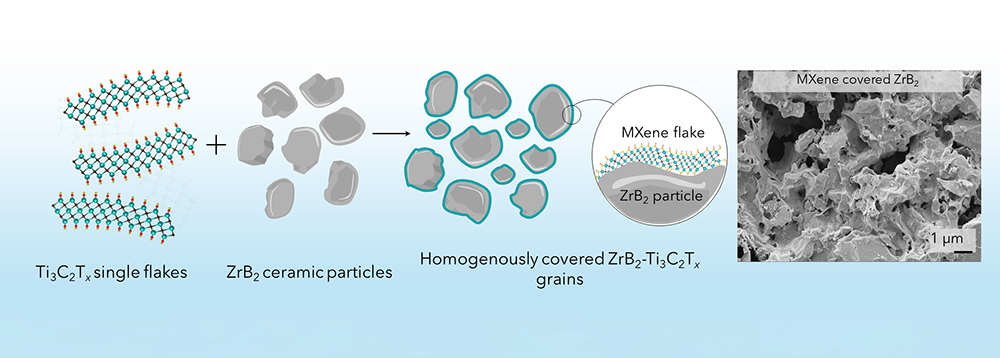

Franklin commissioned London glassblower Charles James to make 37 glass bowls of varying thicknesses and sizes. He then threaded these bowls horizontally on an iron spindle, which could be turned by a foot pedal. This design allowed players to produce numerous notes or chords at a time, like a piano.

Franklin debuted the glass “armonica,” a name derived from the Italian word for harmony, in 1762. The glass armonica became so popular that renowned composers such as Beethoven, Mozart, and Donizetti wrote music for the instrument. (Listen to Mozart’s “Adagio in C for Glass Harmonica, K. 356” below.)

Credit: Ars Lyrica Houston, YouTube

Despite its success, the glass armonica became all but forgotten by the 1820s. In a New York Almanack article, Jaap Harskamp, retired curator of the Dutch and Flemish Collections in the British Library, argues that historical musical trends can explain this downfall.

“The expansion of form in Classical and then Romantic composition demanded much larger orchestras. Concert halls swelled in size. There was no longer place for an instrument that derived its beauty from a whisper of vibrations. The armonica was drowned out. The piano took over,” he writes.

In addition, German physician Franz Anton Mesmer’s use of the glass armonica in hypnosis negatively affected the instrument’s reputation.

“Its sound that was originally praised as heavenly and divine, was now experienced as eerie and morbid. It was suggested that the music had disturbing psychological side-effects. Its celestial softness caused nervous disorders, spasms, and epileptic fits. Doctors started to compare notes on armonica-induced melancholia. Cases of hysteria were recorded among audiences. Premature births were blamed on exposure to the instrument,” Harskamp explains.

Though the glass armonica remains largely forgotten, a few musicians such as Dennis James continue to keep the tradition alive. The video below features James describing how he built a glass armonica based on Franklin’s original design and how to play it.

Credit: Rob Scallon, YouTube

Author

Lisa McDonald

CTT Categories

- Education

- Glass

- Material Innovations