[Image above] Samples of cementitious composites containing varied ratios of coral sand and sea sand. Credit: Fan et al., International Journal of Applied Ceramic Technology

It can be hard to imagine sand is a limited resource when soaking in the sun along a large, populated beach. But sand scarcity is a very real concern right now, driven by increasing demand for sand in the construction sector.

Addressing this shortage is far from simple, however. As this CTT post explains, there are many layers to global sand governance, including the fact that not all sand is the same.

Sand forms from different materials and via diverse processes depending on the environment. For example, most desert sand particles are rounded because they have been subjected to the brutal forces of wind. In contrast, riverbed and sea sands usually are more angular, and this geometry makes them better at binding together materials such as concrete for construction.

Because of these differences, certain sands are more suitable for different applications. In other words, the type as well as abundance of sand matters when addressing sand scarcity.

We cannot simply ask Mother Nature to produce more of the most desirable sands. But we can find ways to replace these sands with other types of sand in certain scenarios, which can help spread the demand for sand across various sand types.

In a recent paper, researchers from Wuhan University of Technology in China investigated the potential of using coral sand as an aggregate in cementitious composites.

Coral sand is a type of carbonate sand originating in tropical and subtropical marine environments. Despite its name, coral is not the main component of coral sand. Instead, this sand comes primarily from the bioerosion of limestone skeletal material of marine organisms such as foraminifera, calcareous algae, mollusks, and crustaceans.

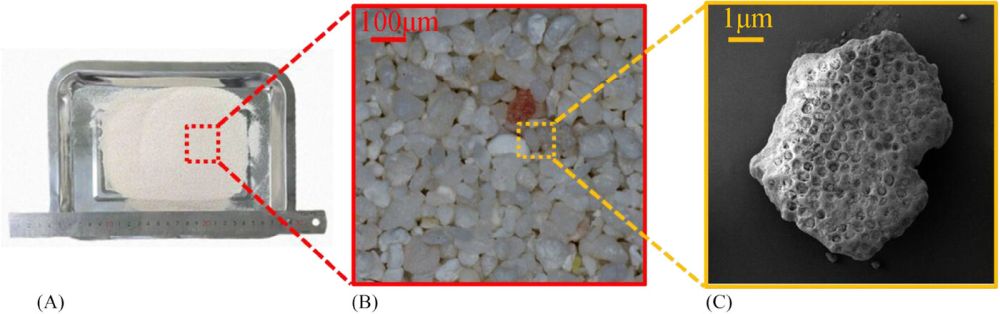

In their study, the researchers sourced coral sand as well as siliciclastic (silicate-rich) sea sand from the South China Sea. Scanning electron microscopy revealed the coral sand had slightly smaller average particle sizes than the sea sand (120 µm vs 140 µm), and the coral sand exhibited abundant pore structures on its surface.

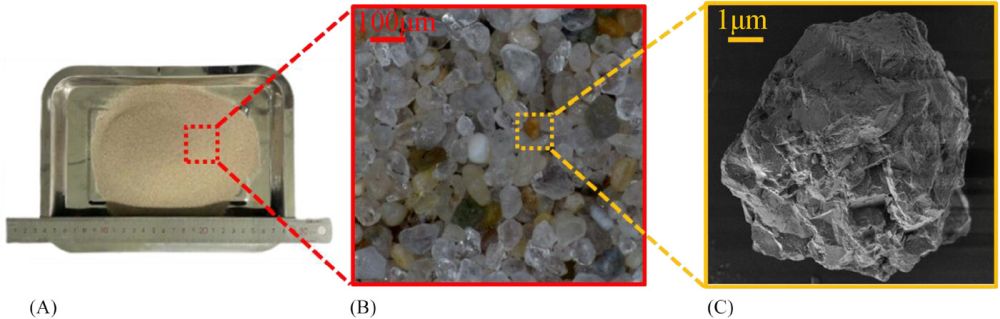

Physical appearance of sea sand: (A) digital camera image; (B) optical microscope image; (C) scanning electron microscope image. Credit: Fan et al., International Journal of Applied Ceramic Technology

Physical appearance of coral sand: (A) digital camera image; (B) optical microscope image; (C) scanning electron microscope image. Credit: Fan et al., International Journal of Applied Ceramic Technology

To create the cementitious composites, the researchers mixed varied ratios of coral sand and sea sand with low-calcium fly ash and ground granulated blast-furnace slag. A solution of sodium hydroxide and sodium silicate was employed as the alkaline activator for the composite’s matrix. Additionally, the composite contained a modified polycarboxylate-based superplasticizer to improve mixture workability as well as polypropylene fibers to improve tensile ductility and crack control.

Testing revealed that as coral sand replaced sea sand in the composite, flowability and drying shrinkage decreased while compressive strength experienced an initial rise followed by a decline. Overall, a 20 wt.% coral sand mixture yielded optimal results, with a compressive strength of 54.4 MPa and tensile strain capacity of 2.397% after 28 days.

“In summary, blending 80 wt.% sea sand with 20 wt.% coral sand … is feasible and promotes sustainable marine construction,” the researchers conclude.

The paper, published in International Journal of Applied Ceramic Technology, is “Sea/coral sand in marine engineered geopolymer composites: Engineering, mechanical, and microstructure properties” (DOI: 10.1111/ijac.14874).

Author

Lisa McDonald

CTT Categories

- Construction