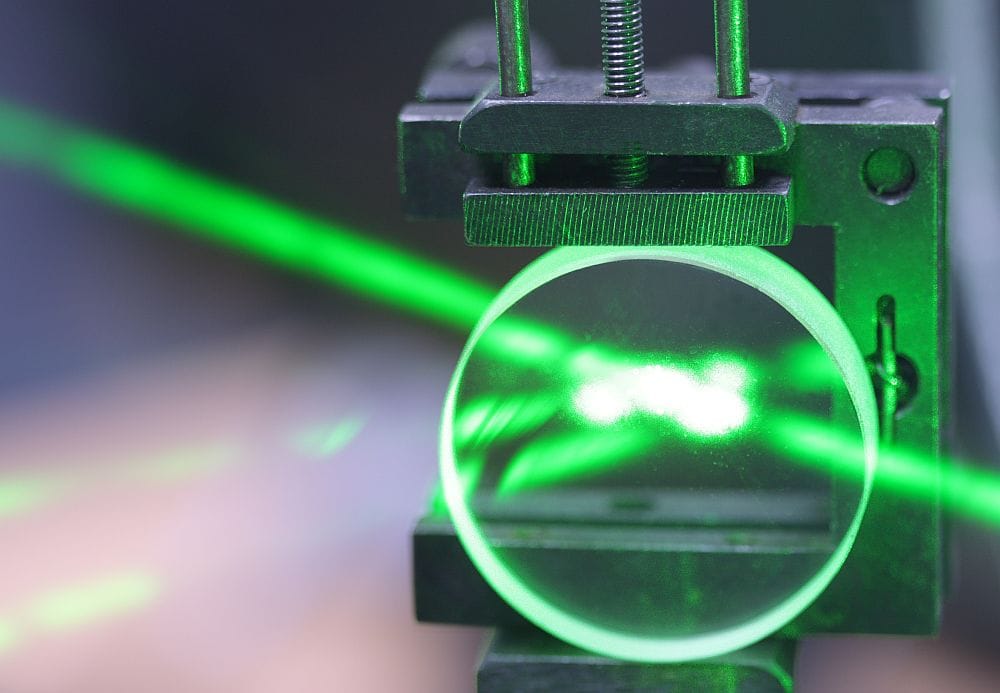

[Image above] One of David Drake’s inscribed pots. This one, dated Aug. 22, 1857, reads “I made this jar for cash | Though it is called lucre trash.” Credit: Garth Clark, Wikimedia (CC BY-SA 4.0)

The southeastern United States has long been rich in clay deposits. In the early 1800s, people living in the Edgefield region of South Carolina took advantage of this natural resource to become a major hub for stoneware production. However, it is all due to the enslaved people who performed the labor-intensive tasks of pottery production that the industry grew as successful as it did.

In his book Turners and Burners: The Folk Potters of North Carolina, Charles Zug, professor emeritus at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, notes how much care and effort the enslaved potters put into their work, even though they did not receive credit for their efforts:

“The work of such potters speaks eloquently to their aesthetic intent; their bold, carefully turned forms, neatly balanced rims and handles, and rich, flowing glazes are a delight to the hand and the eye. Such men were true artists in a world that did not recognize their work, yet they persisted in moving beyond necessity to create works of enduring beauty.”

Unfortunately, most of these potters’ identities will never be known, their existence erased by the impersonal nature of the slavery system. However, some potters defied the odds and had their names documented in the permanent record, providing us the opportunity to honor them by name today.

David Drake, known commonly as Dave the Potter, was an enslaved potter who is now one of the most famous names in Edgefield pottery. Though only a fraction of his work survives to this day, his tendency to inscribe vessels with his name or poems made it possible to piece together the story of his life, which serves as an invaluable look into the lives of enslaved potters.

The following sections overview Drake’s life using information compiled from several sources, including an article by the Chipstone Foundation and the book Etched in Clay: The Life of Dave, Enslaved Potter and Poet by Hungarian-American children’s book author Andrea Cheng. As with any history that is based on scant primary sources, some of the details about Drake’s life may be reported differently depending on the biographer.

For a short summary of Drake’s life, you can watch Jim McDowell, a potter from Asheville, N.C., perform Drake’s story in the video below.

Credit: KET – Kentucky Educational Television, YouTube

Early years: Growing up in the emerging Southern stoneware manufacturing industry

Drake was born into slavery on a plantation in South Carolina around 1800. Based on two mortgage-related documents from 1818, Drake was mostly likely owned by one man, Harvey Drake, from his birth until Harvey’s death in December 1832.

Harvey was the nephew of Abner Landrum, a scientific farmer, doctor, and entrepreneur who played a key role in the birth of South Carolina’s stoneware manufacturing industry. Landrum used his education and access to Jean-Baptiste Du Halde’s The General History of China to develop alkaline glazes for stoneware, which previously were only available in China, Japan, and Korea.

Landrum and his brothers John and Amos founded Pottersville, S.C., a community near the clay-rich town of Edgefield, as the headquarters from which to manufacture their alkaline-glazed stoneware jugs, jars, pitchers, and churns. Hired white workers and enslaved people performed the labor-intensive tasks of digging, hauling, refining, and preparing the clay for the enterprise.

As Harvey was also a business partner in his uncles’ venture, Drake became one of the enslaved people working at the Pottersville factory—setting into motion his lifelong involvement with pottery production.

The beginning of inscriptions

Drake started working at the Pottersville factory when he was about 17 years old, based on the mortgage-related documents mentioned above. His task was to turn the prepared clay into traditional English-shaped stoneware products via the methods of coiling and wheel throwing. His products included huge storage jars that could hold up to 40 gallons—making his pots among the largest to have been made by hand in the United States.

In 1828, Harvey and his brother Reuben purchased the Pottersville factory from Landrum. When Harvey died in 1832, Drake was sold to Reuben and his business partner Jasper Gibbs, but he continued to work at the Pottersville factory.

It was during this time that Drake started to inscribe the stoneware jars he produced with short poems. An article by the late Jill Beute Koverman, who was chief curator of collections and research at the University of South Carolina’s McKissick Museum, describes a fourteen-gallon vessel inscribed with the date July 12, 1834, and the poem “Put every bit all between / surely this jar with hold 14.”

The fact that Drake learned how to write is surprising considering the anti-literacy laws in effect in South Carolina. The state was the first one to make it illegal for enslaved people to learn how to write with the infamous Negro Act of 1740.

In 1834, the same year as Drake’s first inscriptions, South Carolina passed new legislation in response to Nat Turner’s Rebellion that established criminal penalties for teaching either enslaved or free people of color how to read and write. A JSTOR Daily article notes that if an enslaved person was caught reading or writing, authorities may amputate their fingers and toes.

Considering this context, scholars still are not sure when or how Drake learned how to write.

Based on interviews with previously enslaved potters in the 1930s, Drake reportedly lost one of his legs during a railroad accident in the mid-1830s. Nevertheless, he continued to work as a potter, though he required help operating the potter’s wheel.

The Pottersville factory changed hands multiple times in the years following 1836, though all the owners remained related in some way to the original founders. Drake continued to produce pottery at the factory, but in 1840, he was sold to Lewis Miles, John Landrum’s son-in-law. A pot dated July 31, 1840, marks Drake’s transition to Miles’ Stoney Bluff Plantation factory with the inscription “Dave belongs to Mr. Miles, where the oven bakes and the pots bile.”

Missing history: The inscription break of 1843–49

In 1843, Drake was sold to John Landrum, though how this situation came to be is not known. He worked in a pottery factory at Horse Creek, an area about twelve miles south of Pottersville, and then in another nearby pottery factory from 1847–1849 when he was sold to John’s son, Benjamin Franklin Landrum.

There are no known vessels signed by Drake during his time working at the Horse Creek pottery factories between 1843–1849. Scholars suggest that Drake withheld his signature due to the tense atmosphere following an 1841 slave uprising in Augusta, Ga., which made it dangerous for him to broadcast his literacy.

Return of inscriptions and post-emancipation

Drake started signing his work again in 1849, after being sold for a second time to Miles. Inscriptions during this period suggest that Drake had a good working relationship with Miles. For example, an inscription dated June 28, 1854, pokes fun at Miles by saying, “Lm [Lewis Miles] says this handle will crack.”

However, it is important to remember that though Drake was viewed as a master potter, he was still enslaved. On one of Drake’s vessels, an inscription dated Aug. 16, 1857, reads, “I wonder where is all my relations / Friendship to all—and every nation.” The inscription appeared several years after an enslaved woman from his household named Lydia and her two sons were sent away to Louisiana. Though unconfirmed, some sources speculate that these people were Drake’s family, with Lydia being either his wife or sister.

More than 100 known vessels featuring Drake’s inscriptions are dated between 1849–1864. However, his last known poem is dated May 3, 1862, and it comments on the Civil War taking place during that time: “I made this Jar all of cross / If you don’t repent, you will be lost.”

Drake officially changed his name from Dave to David Drake in 1865 upon obtaining his freedom after the Civil War. It is assumed that he continued producing pots based on the 1870 Federal Census for South Carolina, which listed a David Drake, age 70, occupation “turner.” But with no further inscriptions after 1864, it is difficult to confirm other vessels as his.

The 1880 Federal Census for South Carolina does not list a David Drake in the Edgefield District, so it is presumed that he died sometime between 1870 and 1880.

Legacy

In Koverman’s book “I Made This Jar: The Life and Works of the Enslaved African-American Potter, Dave,” she reports that Drake made around 40,000 pots over the course of his life. But only a fraction of his pottery survives today, with the National Gallery of Art estimating that only about 270 are known to survive.

The path toward public awareness of Drake’s story started in 1919, when a pot bearing his name and an inscription was donated to the Charleston Museum in Charleston, S.C. The donation triggered research into the potter’s identity, and through family and business records of his enslavers, much of his biography was reconstructed. It even led to the discovery of Drake’s direct descendants.

Today, there are numerous books, articles, videos, and even a documentary telling Drake’s story. A traveling exhibit called “Hear Me Now,” which first opened at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art in 2022, will be coming to the High Museum of Art in Atlanta, Ga., from Feb. 16–May 12, 2024. The video below provides a look at the exhibit when it was at The Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston from September 2022 to February 2023.

Credit: The Met, YouTube

In 2010, a children’s book was published called Dave the Potter: Artist, Poet, Slave by Laban Carrick Hill. It was a runner-up for the Caldecott Medal, which recognizes the most distinguished U.S. picture book for children, and received the Coretta Scott King award, which recognizes outstanding books for young adults and children by African American authors and illustrators that reflect the African American experience.

In 2016, Drake was inducted into the South Carolina Hall of Fame, about 140 years after his death. His growing fame is reflected in how much his pottery sells for at auction. For example, in 2021, one of his inscribed jar sold for $1.56 million. Unfortunately, none of Drake’s descendants are benefiting from these sales.

We can only wonder what Drake would say if he knew his pottery was being shown in exhibits and sold for such prices. However, Pauline Baker, his great-great-great-great-granddaughter, had this to say in an interview with The Washington Post:

“I hope the people who view our ancestor’s work see that he was resilient, creative, brave, and tenacious. Most of all, I hope they see he was human.”

Further information on the history and impacts of slavery in the United States can be found in digital collections maintained by Duke University, the University of North Carolina at Greensboro, and the Library of Congress. To research ancestors who may have been enslaved, the State Library of North Carolina offers advice on types of records that can aid in the search.

Author

Laurel Sheppard and Lisa McDonald

CTT Categories

- Art & Archaeology

- Education