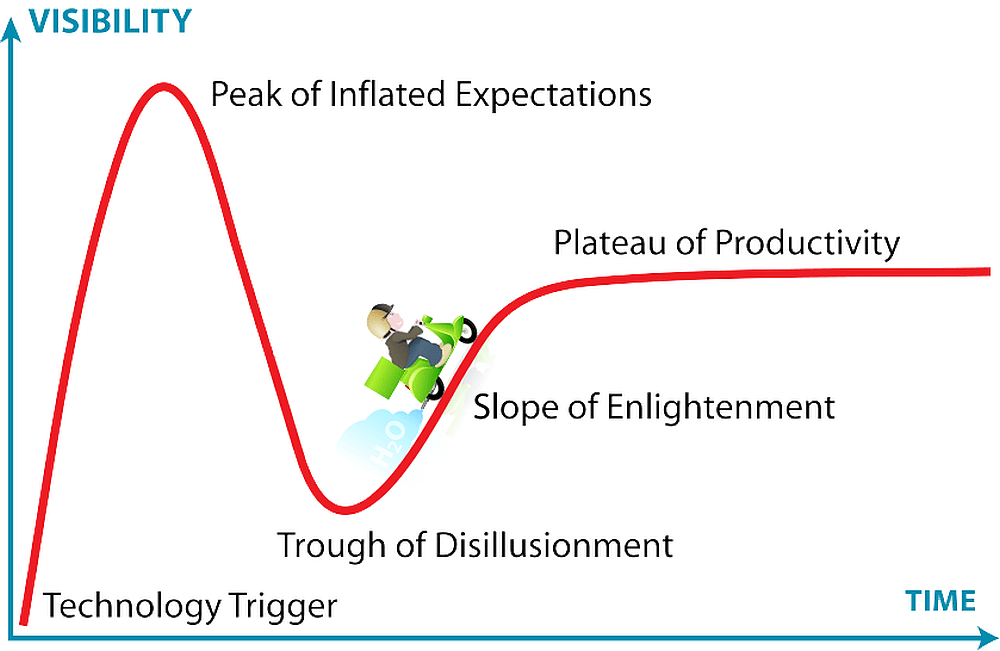

[Image above] A sampling of banded ironstone spear points (except (A) and (C), which are black chert). They were made be prehistoric peoples by edge chipping the stone. Today, edge-chipping failure of ceramics is a serious concern in dental and high-impact applications. Credit: Wilkins; Science, AAAS.

It is hunting season here in the Midwestern United States. Like most modern era humanoids, though, I am a gatherer. My local grocery store with its excellent butcher shop makes it easy to meet the meat needs of my family. However, the hunters among us belong to an unbroken tradition that dates back 500,000 years—200,000 years earlier than was previously thought.

To clarify, it is hunting with stone-tipped spear tools—hafted spears—that was recently discovered to date back so far. Presumably, other effective hunting techniques were employed before these spears were invented, but learning how to shape and attach a stone tip to a stick was an important innovation. The sharp stone points increased the kill probability, however, making them demanded a manufacturing mindset and aptitude from these very early ancestors.

A team of anthropologists and archaeologists led by the University of Toronto report in a new Science article that they have found evidence that Homo heidelbergensis, the last common ancestor between Neandertals and modern man, were innovators. Lead author of the study and UT graduate student, Jayne Wilkins says in a press release, “Although both Neandertals and humans used stone-tipped spears, this is the first evidence that the technology originated prior to or near the divergence of these two species. … It now looks like some of the traits that we associate with modern humans and our nearest relatives can be traced further back in our lineage.”

Hafting—or attaching—stone points to a stick was one part of the innovative technology. The other was the fabrication of the stone tips themselves. The group studied a set of lithic (rock) tips that were discovered at Kathu Pan 1 in South Africa around 1980. Most of the tips were banded ironstone and were shaped near the base to allow hafting. Further analysis showed that the tips, bases and edges had impact fractures that are characteristic of the damage seen when weapons strike targets.

The team confirmed the feasibility of their ideas by replicating the tools and their use. Wilkins says, “The archaeological points have damage that is very similar to replica spear points used in our spearing experiment. This type of damage is not easily created through other processes.”

We do not use edge chipping to make spears anymore, but edge chipping remains a critical issue for modern day ceramic engineers. In an article that will be published in the January/February issue of the ACerS Bulletin, George Quinn explains that edge chipping, the same technique used to make spear tips, is an extremely important, often deleterious issue for ceramics used in dentistry and high-impact applications like ceramic piston heads. The article (look for it online in late December) will address the challenges associated with accurately and reproducibly testing edge chipping and includes a look back in time to see what lessons can be gleaned from those early engineers.

Happy Thanksgiving to all, whether you a hunter or gatherer be.

Author

Eileen De Guire