[Image above] The Ponce de Leon Inlet Lighthouse and Museum. Credit: Kim Seng; Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

On January 24–29, 2016, the 40th International Conference and Expo on Advanced Ceramics and Composites, ICACC’16, will descend upon Daytona Beach, Fla., for some serious materials science.

[Don’t forget to register before Dec. 23 to save!]

The conference venue, the Hilton Daytona Beach Resort and Ocean Center, will be teeming with the latest research on advanced ceramics and composites—but there’s plenty more to learn about ceramic and glass materials beyond the walls of the Hilton.

Just 12 miles from the Hilton Daytona Beach is Florida’s tallest lighthouse and the nation’s second tallest brick lighthouse (Cape Hatteras Lighthouse in North Carolina takes first place).

The Ponce de Leon Inlet Lighthouse is a looming structure—standing 176 feet tall, the tower provides an impressive view of Florida’s coast and the Atlantic Ocean.

The north-facing view from atop the Ponce de Leon Lighthouse, towards Daytona Beach. Credit: Greg Phelps

The tower consists of about 1.25 million bricks, and while these aren’t advanced ceramics, its construction was quite advanced for its time.

The Ponce de Leon tower, completed in 1887, used the first moveable working platform during its construction. Masons omitted bricks from the outside of the tower every 10 feet, and into those holes they inserted a construction platform that could be moved as needed. Invented for the Ponce de Leon tower, this clever early scaffolding was adopted as a standard construction technique for other brick lighthouses.

In addition to a clever construction design, the Ponce de Leon Lighthouse can stand tall against the ocean’s assaults—its tower has brick walls that are 8-feet thick at its base and narrow to 2-feet thick at the top of the tower. Those walls aren’t solid brick, however. “The tower consists of an inner and outer brick wall connected by interstitial brick walls, similar to the spokes of a wheel,” according the a National Historic Landmark study on the lighthouse website. “While the outer wall tapers, the inner wall retains a constant 12-foot diameter.”

That configuration lessens the amount of material needed to construct the tower and lightens its overall weight, while still providing adequate structural support against ocean waves, storms, and winds.

If you visit the lighthouse, you can climb all the way up its beautiful internal spiral staircase to the tower’s crowning heart—a lantern to notify ship crews of Florida’s shoreline from a height of 168 feet above sea level.

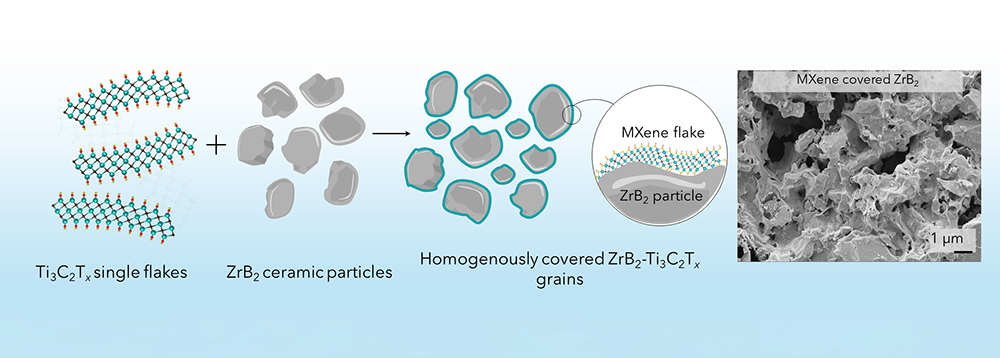

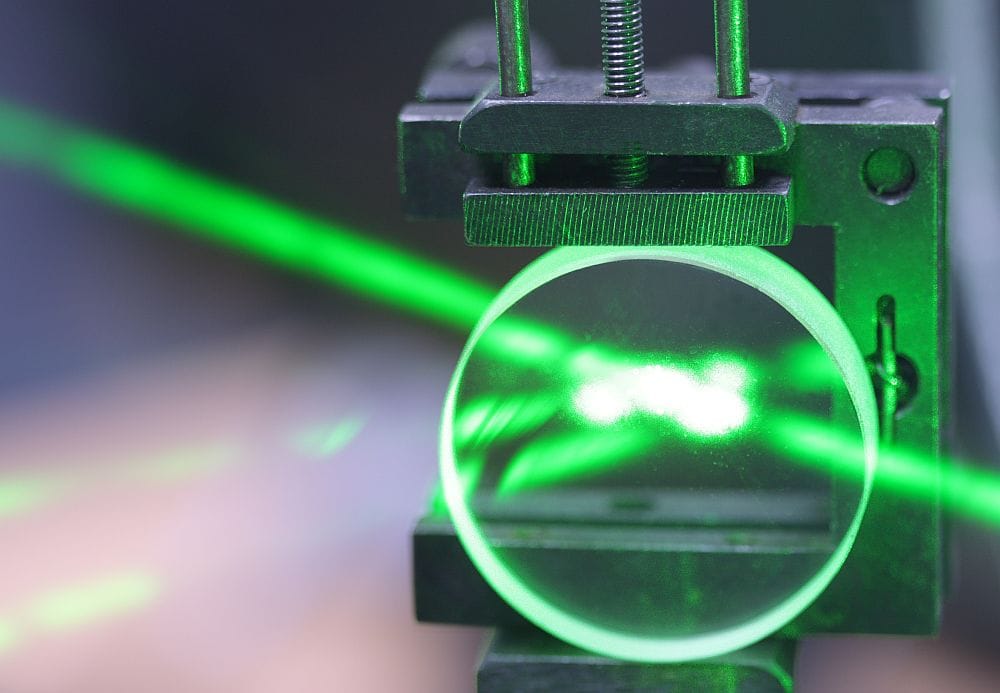

The lighthouse’s original lens—a first-order Fresnel lens, the largest type of Fresnel lens—could magnify the light from an oil lantern into a guiding beacon shining out to sea.

A Fresnel lens is a compact type of lens consisting of concentric rings that found particular utility in lighthouses because its design uses less material than a standard lens.

The lens in the Ponce de Leon Lighthouse is a behemoth antique that’s a rather impressive engineering accomplishment for the time it was built in 1867. “The lens was illuminated originally by a first-order hydraulic kerosene lamp with five concentric wicks, creating a light of 15,000 candlepower which could be seen 20 nautical miles out to sea,” according to the Ponce de Leon website.

According to the lighthouse aficionado website Lighthouse Friends, the lens “was somewhat unique in that the landward side of the lens was composed of three concave reflecting panels.”

The NHL study on the website for the Ponce de Leon Lighthouse and Museum offers more details about the original lens:

The lens without its cast-iron pedestal weighed about 2,000 pounds. With a diameter of 71½ inches, the beehive-shaped, classical Fresnel lens was a stationary, fixed-light lens consisting of 15 glass prism panels, three silvered, concave brass reflector panels, and brass framing which form a hollow cylinder 8½ feet high. The 15 glass prism panels facing the ocean consisted of lower, central, and upper panels, forming five glass sections. Each of these five sections covers 45 for a total of 225. The five lower glass prism panels contained eight thick triangular catadioptric prisms each. The five central prism panels contain a wide refractive belt prism with eight narrow triangular dioptric prisms above and eight below the belt. The five upper glass prism panels contain 18 thick triangular glass prisms. Opposing the five central prism panels, on the landward side of the lens, were three silvered, concave brass reflective panels, a rare feature for lenses of this period, covering a total of 135. These served to reflect the light from the light source towards the ocean-facing glass prisms. The lens was mounted on a six-foot tall cast-iron columnar pedestal, and as the lens was a fixed, steady light character, no rotation mechanism was utilized.

Although the original lens was removed from the lighthouse when it was electrified in 1933, it and many other lenses can be viewed in the Ponce de Leon Lighthouse’s Ayres Davies Lens Exhibit Building, one of the largest collections of restored Fresnel lenses in the world.

Glass Fresnel lenses are now worth a hefty price tag, as modern replacements are made of much lighter, cheaper, and easier-to-manufacture plastic.

So while you’re at ICACC’16, make the short trip to visit the Ponce de Leon Lighthouse, which is open daily. And, if you arrive in Daytona Beach just one night early, you can toast to the full moon atop the tower with drinks and hor d’oeuvres and a spectacular Floridian view.

Author

April Gocha

CTT Categories

- Construction

- Material Innovations

- Optics