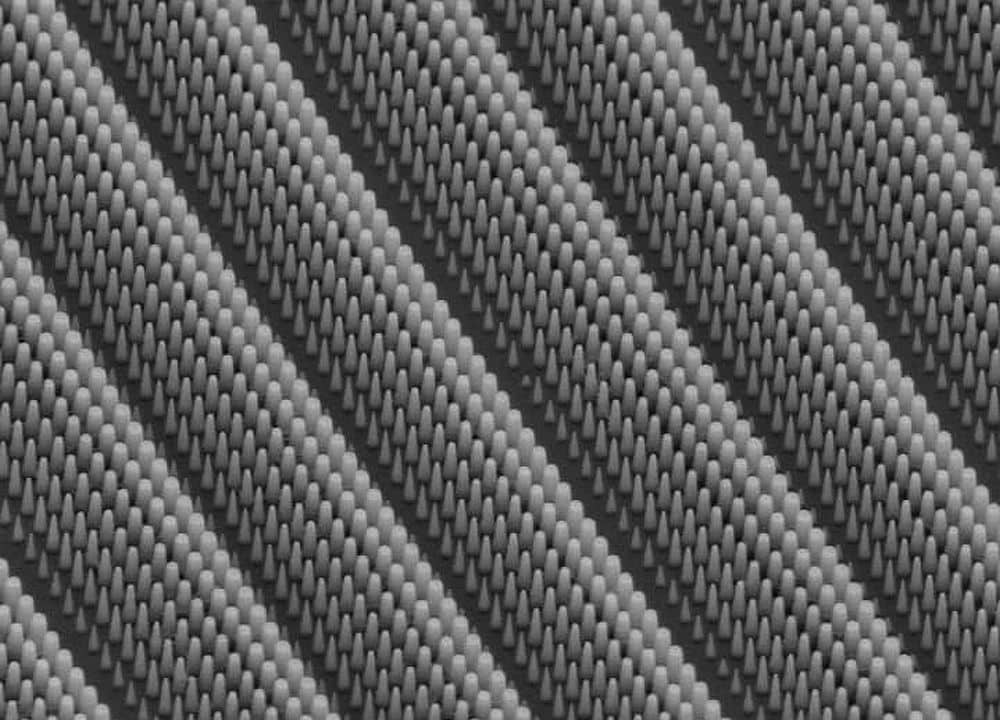

[Image above] Besides lighthouses, Fresnel lenses also played a big role in the railway industry as signals that projected a coherent light beam over great distances. Credit: Friva, Shutterstock

The world owes a debt to Augustin-Jean Fresnel, the French civil engineer and physicist who invented the eponymous lighthouse lens. His invention saved countless lives by improving maritime navigation, as shown in an August 2025 CTT.

What many people may not realize, however, is that the Fresnel lens left a lasting mark on yet another industry: railways. Today’s CTT will shine a light on this chapter of the lens’s history.

Augustin-Jean Fresnel: The man behind the invention

Fresnel was born in 1788 as the frail second son of a French architect and a lawyer’s daughter. Despite his initial difficulty in communicating verbally, he had a gift for math. Once he joined his older brother, Louis, at a science and mathematics school in Caen, France, Fresnel began to thrive.

In 1804, Fresnel was selected to study at École Polytechnique in Paris, which was considered the best French engineering university. After that, he was given a spot at the French National School of Bridges and Highways, the world’s oldest school of civil engineering, within École Polytechnique. Upon graduation, Fresnel was assigned to repair canals and highways as part of French Emperor Napoleon Bonaparte’s plan to construct a complete network of roads across France (so he could quickly put down any rebellion).

On his own time, Fresnel continued his studies and experimented with light and optics. The prevailing theory at the time was Newton’s view of light as particles, but no one had been able to explain diffraction. Fresnel thought it could be explained if light was, in fact, a wave. The dual nature of light is now accepted as scientific fact, but at the time it was controversial. Disagreeing with Newton was tantamount to heresy.

Fresnel’s work slowly gained approval, however, and in 1819 he was appointed secretary to the French Commission for Lighthouses. In that same year, he proposed a practical application of his wave theory of light: a stepped lighthouse lens made of concentric rings of prisms to reduce the lens’s weight and force the light into straight beams that were visible for miles. The Fresnel lens was born, and innumerable ship personnel and passengers were saved.

Fresnel lens manufacturing

The path to illumination was not an easy one, however. Many challenges needed to be overcome to enable the manufacturing of the large, annular prisms, which needed to be perfectly clear and free of defects. In the early years, this precision was achieved by hand grinding and polishing glass. Today, Fresnel lenses are often made of optical polymers and can be made by pressing or injection molding, 3D printing, or computer numerical control cutting, among other techniques.

The largest lighthouse Fresnel lens is in the Makapu’u Point Lighthouse on Oahu in Hawai’i. It is 12 feet tall and 8 feet wide. It was manufactured in France and then exhibited at the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair and the 1907 Jamestown Exhibition in Virginia before being installed in the lighthouse in 1909.

Fresnel lenses in railway signaling

Fresnel lenses are most well-known for their use in lighthouses, but this innovative glass lens dramatically changed the railway industry as well. The spread of tracks and steam-powered trains across great distances revolutionized how people manufactured and sold goods, traveled, and obtained fresh food. But increasing traffic on the railways led to communication problems that caused accidents. It was necessary to devise a system for notifying oncoming trains of stopped or delayed trains ahead, hazards on the tracks, or switch positions.

Early attempts at railway signaling involved simple lanterns, colored flags, or semaphore arms. These options all had visibility issues, especially at night or during storms. Railways needed a robust, highly directional light source to communicate quickly over long distances and prevent accidents, especially with increasing train speeds. Lighthouses were the obvious inspiration for such a signaling system, but the lights needed to be much smaller and, preferably, portable.

To me, here is where the story really gets interesting. In the early 1800s, Fresnel lenses were still made in France by hand. This manual process made them expensive and difficult to import. To miniaturize them and enable mass production, a source in the United States was required. In 1852, John Gilliland of the Brooklyn Flint Glass Company patented a method for manufacturing pressed and molded lenses based on Fresnel’s design for use with railways and ships.

The Brooklyn Flint Glass Company moved to a sleepy upstate New York town in 1868 and renamed itself the Corning Flint Glass Company, the ancestor of today’s Corning. The manufacturing equipment arrived in Corning from Brooklyn via the Hudson River, the Erie Canal, Seneca Lake, the Chemung Canal, and finally a feeder branch of the canal. The equipment’s voyage to Corning was recreated in 2018 by Corning’s GlassBarge.

Another Corning acquisition, the MacBeth–Evans Glass Company (well known for their Depression glass), had developed an improved Fresnel-style lens using flint glass, the result of a request from the U.S. Lighthouse Bureau. Their design was used in the first fourth-order Fresnel-style lens produced in the United States. In addition to their flint glass lenses being optically superior to the crown glass used in Europe, the lenses were completely manufactured by machine, which made them much more consistent.

The highly focused beam of the Fresnel lens made railway signaling practical by projecting a coherent signal light beam over great distances. The lens minimized light dispersion and reduced confusion from neighboring tracks, which was especially useful for large urban stations or industrial yards. The lenses were so good at projecting light that they were adopted for locomotive headlights as well.

Tinting could be added to the glass lens to create signal lanterns for specific purposes. The importance of lighted railway signals was described in a series published by Railway Wonders of the World in 1935.

The evolution of railway signaling (post-Fresnel)

Pressed-glass lenses for lanterns and signal lights quickly became ubiquitous. Railroad signal light colors were standardized in 1905 as red, yellow, green, blue, purple, and white, created with various glass additives. (Read more about the chemistry of colored glass here.)

The signal light colors had to fall within specific chromaticity (light quality) values, which were tightly controlled. The colors held specific meanings and could be configured in combinations of two or three lights to expand their usefulness. Making the lenses from glass provided resistance to heat (from the light source) and the environment (such as weather and dust).

Today’s railroad signals are evolving to use LED light sources, which reduce their reliance on lenses for amplification. Combining the signaling system with positive train control systems, which were mandated on U.S. mainline railroads as of 2015, has further improved railroad safety. With advances in signaling technology and autonomous train operation, many light rail and subway systems are evolving to run automated trains with no onboard human driver.

Fresnel’s lasting legacy

The Fresnel lens design is still found today in many applications beyond railway signaling, including stage lighting, vision correction, and solar concentrators—a testament to its ingenious simplicity and manufacturing quality. The interplay of glass and light continues to drive innovation and fascinate artists and engineers. Augustin-Jean Fresnel would be pleased.

Author

Becky Stewart

CTT Categories

- Education

- Glass

- Optics

- Transportation

Related Posts

Sports-quality ice: From pond side to precision Olympic engineering

February 12, 2026