Although there is a tendency to associate little plastic bottles with pharmaceuticals, people with severe allergies (who carry anti-anaphylactic shock medicinals, such as EpiPens and similar auto-injectors), for example, know there is branch of pharmaceuticals that relies on glass packaging. And, of course, nearly everyone is familiar with the glass bottles doctors and nurses draw medicines from with hypodermic needles.

According to the American Pharmaceutical Review website, 98 percent of injectable medications come in glass containers, an amount that translates into 23 billion glass primary pharmaceutical containers produced and used worldwide each year.

To oversimplify a bit, glass is popular because it is transparent, inert, easy to clean and fairly strong. The latter is a relative term. Some pharmaceutical containers can be made with thicker walls where weight is not a concern, such as in a doctor’s office. On the other hand, rugged lightweight glass containers may be important for portable first-aid kits and personal devices. Production of personal injectables can be particularly tricky because the containers must be rugged enough not to break accidentally, but easy enough to shatter and release their contents when needed. Some personal devices require a glass ampoule to be crushed or snapped before use, whereas others (such as those used in combat situations) have a pin mechanism that quickly fractures the glass container when the unit is jabbed into the body.

But, despite the fact that glass drug containers have been around for a very long time, new uses and new pharmaceuticals continue to challenge the ability of manufacturers to keep up. However, some manufacturing techniques have run into problems and forced drug recalls, apparently because the contents interacted with the glass to cause delamination to occur.

Along these lines, the strength and resilience of pharmaceutical glass apparently was a hot topic at a recent meeting of the International Commission on Glass. In early March, the ICG convened a special workshop in Berlin with a group experts from the glass and pharmaceutical industries to discuss their future R&D needs and to map a course for continued development of unbreakable and chemically resistant glass. (Keep in mind that just as beer brewers don’t make their own bottles, drug companies purchase glass containers from specialty manufacturers according to specifications established by the purchasing company.)

Presentations included ones from Georg Rössling (president of the European arm of the Parenteral Drug Association), Ronald G. Iacocca (senior research advisor at Eli Lilly and Co.), Volker Rupertus (senior executive for quality at Schott Pharmaceutical Packaging), Daniele Zuccato (Nuova Ompi, Stevanato Group), Emanuel Guadagnino (Nuova Ompi, Stevanato Group), Bruno Reuter (Gerresheimer Glass) and Wigand Weirich (F. Hoffman La Roche).

A release from the ICG reports that the meeting fostered a “better understanding of the interaction of the glass surface with pharmaceutical products, including delamination phenomena, adsorption effects and the influence of big molecules, were seen as short term projects” that could be addressed by 2015. The CGI went on to say that other issues related to glass quality variances, extractable and leachable metal ions, and lubricants could also be solved by around 2015. However, the group says that more years would be needed to address “the fragility of glass which creates problems in handling and device usage, transport and also particle contamination [such as] the effect of silicon oil and the de-activation of large molecules.”

Participants also recommended the ICG to create a technical committee on glasses for pharmacy.

The issue regarding “the fragility” of glass is a longer-term matter because it gets at a core question that has yet to be solved by glass researchers: Why does glass lose so much of its intrinsic strength between its creation and final use?

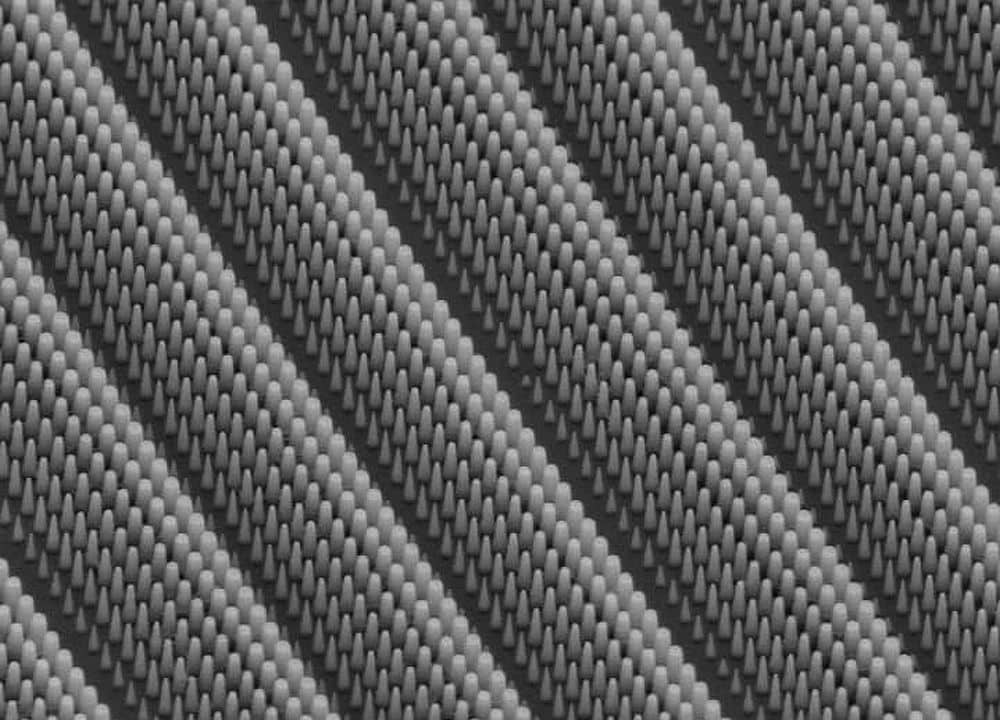

Glass experts often remark that despite being very strong at first, glass retains less than 1 percent of its initial strength because of mechanical and chemical effects. Thus, glass must often be subjected to post-formation strengthening techniques, such as chemical or thermal tempering.

Indeed, the issue of solving the riddle of retaining intrinsic glass strength is of great concern and great hope among glassmakers and users. The cover story of the May issue of ACerS’ Bulletin will report about efforts to form and fund a “Usable Glass Strength Coalition” that would unite researchers, private industries and government in a groundbreaking effort.

CTT Categories

- Basic Science

- Glass

Related Posts

Sports-quality ice: From pond side to precision Olympic engineering

February 12, 2026