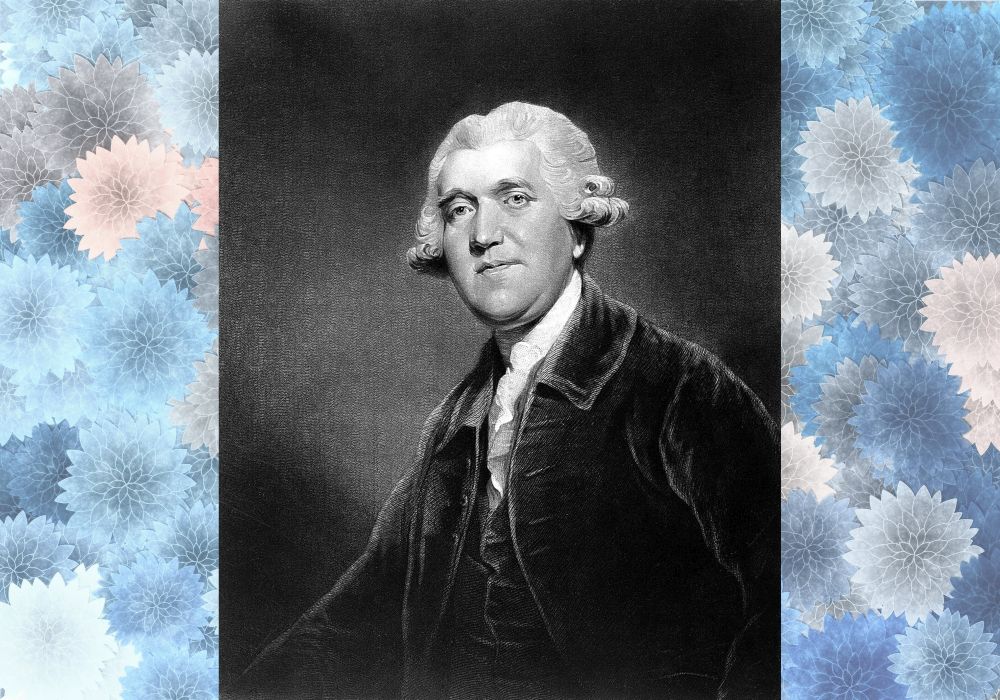

[Image above] Portrait of Josiah Wedgwood, an innovative potter often cited as the father of modern marketing. Credit: Wellcome Collection (CC BY 4.0); Dmitri Posudin, Pexels

Fine china enthusiasts are sure to recognize the term Wedgwood, a British brand of beautiful dinnerware, teaware, and other luxury ceramic products. But the man after which this brand is named, Josiah Wedgwood, is so much more than just a potter. He’s been called the “Steve Jobs” of the 18th century, and “one of the most innovative retailers the world has ever seen.”

Today’s CTT explores the history of this intrepid entrepreneur and marketing genius, including the use of his innovative designs to help support arguably the most morally charged cause of his day—the abolition of slavery.

Early years

Born on July 12, 1730, in Burslem, England (part of Staffordshire Potteries), Josiah Wedgwood was the thirteenth child of an impoverished and struggling potter, Thomas Wedgwood, and his wife, Mary Stringer. At the early age of nine, Josiah along with his brothers took over their father’s business following their father’s death. He and his brothers slung clay and made pottery in backbreaking 12-hour days to support the rest of the family.

Under these poor working conditions, Wedgwood contracted smallpox, leaving his right knee damaged (later in life he had the leg amputated because of chronic pain). This physical impairment limited his ability to do manual labor, so he concentrated on the business side of pottery, which included marketing and sales, as well as the science and chemistry behind the manufacturing processes.

During his 20s, Wedgwood partnered with renowned potter Thomas Whieldon. During the period 1754 to 1759, he and Whieldon developed an exceptionally brilliant green glaze and unique tortoiseshell glaze, respectively, which became in high demand. This experience helped Wedgwood realized that “Invention without experiment signifies very little. Everything derives from experiment.”

Wedgwood returned to Burslem to open his own shop (the Wedgwood company still exists today), where he experimented with new glazes and finishes. His experiments required thousands of trial pieces before coming up with the perfect composition.

Ceramic innovations

One of Wedgwood’s first well-known innovations was his variation of creamware, a durable earthenware alternative to porcelain. His variation won a national competition in the 1760s, which challenged potters to design a complete tea set for Queen Charlotte.

Wedgwood capitalized on this name recognition, branding his product as Queen’s Ware. He opened an exclusive shop in London to display his creamware, which became the basis for the Wedgwood brand (one of the first luxury brands in British history).

Example of Queen’s Ware. Credit: Tangerineduel, Wikimedia (CC BY-SA 4.0)

Wedgwood’s next major invention was jasperware in the mid-1700s. This fine-grained stoneware, which contained a sulfate form of barium, was developed to take advantage of the growing interest in antiquities. Jasperware had a matte finish in a variety of colors, with the most popular pale blue decorated with white, cameo-like reliefs.

Example of jasperware. Credit: Daderot, Wikimedia (Public domain)

Queen’s Ware and jasperware were soon selling around the globe, along with other ceramic products. Capitalizing on the popularity of tea in the U.S. and lack of domestic luxury pottery manufacturers, Wedgwood began exporting his wares there from Liverpool. He also set up warehouses and showrooms at Bath, Dublin, and Westminster to help increase sales.

By 1784, Wedgwood was exporting nearly 80% of his total production, and six years later, he was selling his wares in every city in Europe.

There are two other major ceramic feathers in Wedgwood’s cap that deserve callouts, The first was the Frog Service dinner and dessert set that he produced for Empress Catherine the Great, which consisted of 952 pieces, each featuring hand-painted illustrations. Large crowds came to see the display of these items.

The second feather to acknowledge is that, after three years of development, Wedgwood produced a replica of the Portland Vase, a blue-and-white glass vase dating to the first century BCE. The replica is considered the most difficult pottery Wedgwood ever made, and once he considered the design perfect, the replica was shown in London by ticket only. Wedgwood subsequently made about several dozen copies he considered perfect.

Marketing and science innovations

Wedgwood is often credited as a pioneer of modern marketing due to his expertise in tracking market trends and capitalizing on them. For example, once creamware was no longer popular with the upper class, Wedgwood reduced the price and marketed it to the lower classes.

When other potters copied his innovations, Wedgwood responded by introducing new products and new ways to sell them. The latter included money back guarantees, free delivery, free returns on damaged goods (to reduce these losses, he helped establish a major transport canal), direct mail, self-service, buy one get one free, illustrated catalogues, and door-to-door sales.

Wedgwood was also famous for building one of the first company towns. After building a modern factory in England called Etruria in 1769 on the new canal, he constructed 42 residential units next to the factory for his workers. Rules were strictly enforced, and workers (called Etrutians) were required to punch the clock when they arrived.

Etruria, which operated for 180 years, was built north of Stoke to produce vases made from black stoneware. These vases resembled those of Etruscan or Greek excavated from the Etruria district in Italy at the time. This success added another moniker to Wedgwood’s list: “Vase Maker General to the Universe.”

A self-taught scientist, Wedgwood also made scientific contributions to the pottery industry. His paper to the Royal Society on the development of the first standardized pyrometric device helped him be elected to the Society in 1783.

A pyrometric device helps determine the appropriate firing parameters by measuring shrinkage or deformation of a regular shape. Coincidentally, I worked for the Orton Ceramic Foundation one summer making pyrometric cones, so I have personal experience with this device!

Abolitionist activities

Wedgwood was not only an expert potter. Influenced by his Unitarian beliefs, he became a prominent abolitionist fighting slavery. He produced the anti-slavery medallion, Am I Not a Man And a Brother? for Joseph Hooper, a founder of the Society for Effecting the Abolition of the Slave Trade.

The medallion helped bring public attention to abolition as it became worn as part of watch chains, bracelets, and other forms of jewelry. Thousands of smaller medallions were given to supporters for free, including Benjamin Franklin, who said that the medallion did far more for the cause than any letters could do.

Wedgwood’s personal and professional legacy

Wedgwood managed to find time during his busy career to fall in love and have a family. In 1764, he married his third cousin, Sarah “Sally” Wedgwood, daughter of Richard Wedgwood, a wealthy cheese producer. Josiah and Sarah had eight children, including several daughters who carried on Wedgwood’s legacy and genius:

- Sarah was a founding member of the Birmingham Ladies Society for the Relief of Negro Slaves, the first anti-slavery society for women.

- Susannah or “Sukey” married Robert Darwin and became the mother of the English naturalist Charles Darwin. Charles married his first cousin, Emma Wedgwood.

Wedgwood’s success continued until his death on Jan. 3, 1795. He died one of the wealthiest people in England with a fortune of about £600,000 (equivalent to more than US$100 million in today’s currency).

“Wedgwood helped design Britain,” says historian A.N. Wilson. “He left a lasting impact on design, commerce, and human rights.”

Further reading

Learn more about the six pottery towns of Stoke-on-Trent.

Read Brian Dolan’s 2004 book, Wedgwood: The First Tycoon.

View the Wedgwood collection at the Victoria and Albert museum.

Another book by the director of the Victoria & Albert Museum, Tristran Hunt, The Radical Potter.

Some historic Wedgwood pottery on loan can also be viewed at this Australian museum.

The Creative Giant documentary explains Wedgwood’s career through five major products he developed.

Planning a trip to Stoke-on-Trent to see the potteries? Read some tips here or find out more here.

Author

Laurel Sheppard

CTT Categories

- Art & Archaeology