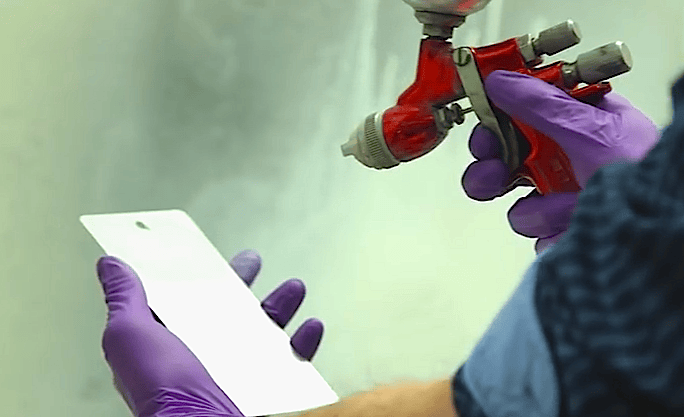

[Image above] Screen capture from American Chemical Society’s video about new glass-based paint developed by scientists at Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory. Credit: American Chemical Society; YouTube

Sometimes it’s necessary to harness the sun’s energy to power our buildings… and other times we want to reflect that sunlight away from us at all costs to keep those same buildings cool and our energy bills down.

And there’s been no shortage of research in the glass industry when it comes to figuring out the most efficient ways to harvest (or block) sunlight depending on our energy needs du jour.

This summer, we reported about the latest advancements in smarter materials for windows that are leading to innovations in energy efficiency.

We also covered research from Georgia Institute of Technology in Atlanta, where scientists developed an electrochromic polymer coating that allows glass to darken or turn clear on demand by a small user-controlled electric current.

But what about structures that can’t be constructed from glass—like naval ships, metal roofs, car doors, and those baseball bleachers that burn your legs during a hot afternoon game? How can we keep those surfaces cool and resistant to corrosion when hammered by years of blazing direct sunlight?

A team of scientists from Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory (Laurel, Md.) might have the answer.

The team has developed a glass-based paint that reflects light off metal surfaces to keep them cool and protects those surfaces from corrosion accelerated by the harsh rays of the sun. They presented their research August 17 at the 250th National Meeting & Exposition of the American Chemical Society (ACS) in Boston.

Jason Benkoski, senior scientist at Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory, and his team designed a silica-based paint to “reflect all sunlight and passively radiate heat, keeping damage from the sun at bay,” according to a video produced by ACS about the research.

Credit: American Chemical Society; YouTube

“Most of your damage, whether it’s corrosion or aging or any other type of deterioration, gets accelerated at high temperatures,” Benkoski says in the video.

To develop the new paint, Benkoski used “a lot of chemistry… and a lot of laundry hampers,” he demonstrates in the video. He measured the temperatures of various experimental coatings by placing test plates inside hampers to control for wind and ground temperature.

“It was a pretty inexpensive solution that actually controls for convection… it controls for conduction… and it’s really convenient,” Benkoski says.

Back in the lab, Benkoski settled on a paint derived from silica, one of the most abundant materials on earth, and the main compound in glass.

“Most paints you use on your car or house are based on polymers, which degrade in the ultraviolet light rays of the sun,” Benkoski says in a related ACS news release. “So over time you’ll have chalking and yellowing. Polymers also tend to give off volatile organic compounds, which can harm the environment. That’s why I wanted to move away from traditional polymer coatings to inorganic glass ones.”

And because it’s almost entirely inorganic, that means it will last a lot longer than those more conventional, polymer-based paints.

“It’s almost like painting a rock on top of your metal. This thing’s going to last not for tens of years, but maybe hundreds of years,” Benkoski says in the video.

Benkoski’s lab is developing the paint primarily for use on naval ships, but it has many other commercial applications—including cars, roofs, and any outdoor equipment. The team plans to begin field-testing the material in about two years, so stay tuned for further developments.

Author

Stephanie Liverani

CTT Categories

- Glass

- Manufacturing

- Material Innovations