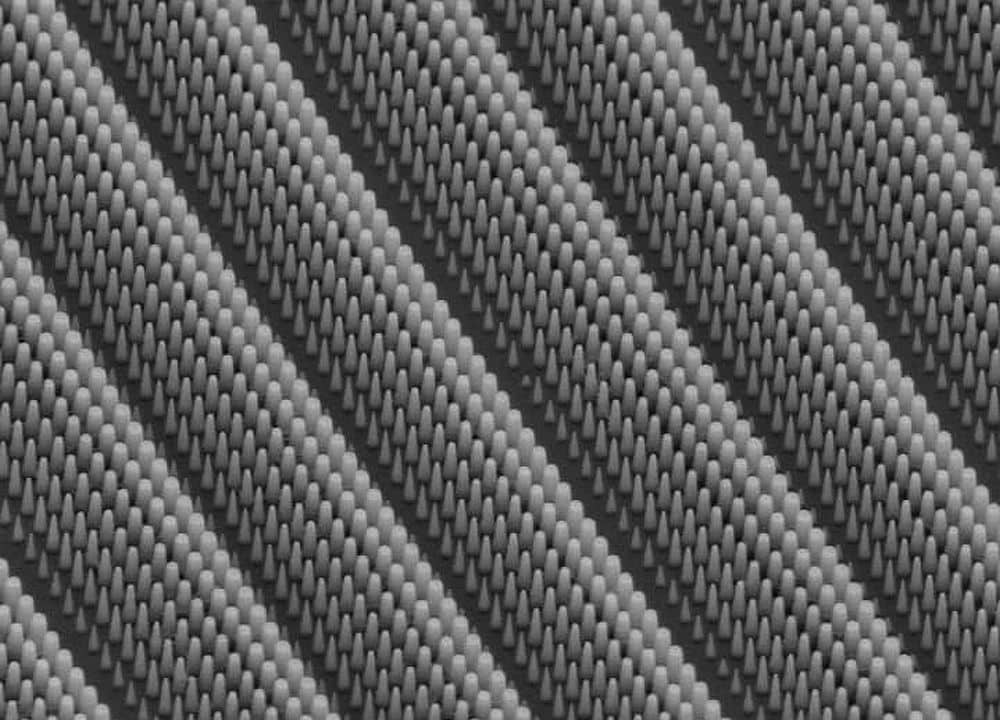

[Image] Pemaquid Point Light is one of only eight Maine lighthouses that still have their original Fresnel lenses. Pictured is the Fourth Order Fresnel lens in the Pemaquid beacon tower, which was installed in 1862. Credit: Lisa McDonald

Growing up in land-locked Iowa, and now living in central Ohio, I rarely find myself around large bodies of water. As such, I typically give little thought to the maritime industry, even though it is a vast sector responsible for transporting more than 90% of global trade by volume.

This past June, however, I gained a new appreciation for seafarers during a road trip up the coast of Maine with my dad. As we drove from Portland to Lubec along the fourth longest coastline in the United States, we learned about the state’s rich shipbuilding history from the Maine Maritime Museum in Bath and even enjoyed a sunset sail on a traditionally constructed wooden schooner in Camden.

Along the way, we stopped by five of Maine’s most well-known lighthouses: Portland Head Light, Pemaquid Point Light, Owls Head Light, Bass Harbor Head Light, and West Quoddy Head Light. Among the various facts that I learned at each place, the one that grabbed my attention as a perfect topic for Ceramic Tech Today is that the latter four lighthouses still use original or restored Fresnel lenses—an early 19th century lighting innovation that revolutionized lighthouse technology.

Early lighthouses and reflector systems

Coastlines are filled with geological formations that can be dangerous for ships, including rocky outcrops, reefs, sandbars, and shallow waters. In dark and foggy weather especially, mariners can struggle to identify and avoid these navigational hazards.

Thousands of years ago, before maritime activities grew into an established industry requiring clearly defined ports, mariners used fires built on hilltops to guide their ships to safety. These fires were sometimes placed on a platform to improve visibility, and this practice led to the development of the first lighthouses.

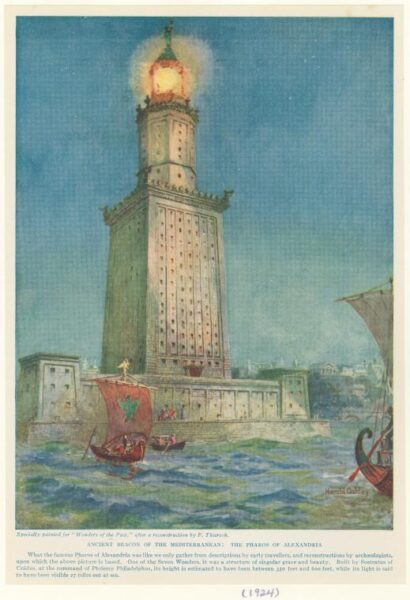

Drawing of the Pharos of Alexandria based on descriptions by early travelers. This lighthouse is considered one of the Seven Wonders of the World. Credit: The New York Public Library (Public domain)

Arguably the most famous lighthouse from antiquity is the Pharos of Alexandria. This structure, which was built by the Ptolemaic Kingdom between 280 and 247 BCE, is estimated to have been 100 meters (330 feet) tall, with some accounts even suggesting 135 meters (443 feet). This height made it one of the tallest human-built structures in the world for many centuries, until it was badly damaged by multiple earthquakes between 956 and 1323 CE.

To enhance the distance from which lighthouse fires could be seen, early lighthouses installed polished metal reflectors to direct light more effectively. However, wood and coal were typically used to fuel these fires, which produced large amounts of smoke that rapidly blackened the reflectors and diminished their reflection capabilities.

In the 1780s, Swiss scientist Aimé Argand invented an oil lamp with a steady, smokeless flame. This invention was made possible by a glass chimney, which ensured an adequate current of air up the center and the outside of the circular wick for even and proper combustion of the oil. The Argand lamp subsequently became the principal lighthouse illuminant for more than 100 years.

The introduction of this reliable and steady illuminant enabled the development of effective optical apparatuses for increasing the intensity of the light—most notably, the Fresnel lens.

Lenses before Fresnel

Before the Fresnel lens, which will be explained in detail in the following section, several glass lenses were considered as replacements for polished metal reflectors. However, as explained in an article by the United States Lighthouse Society, many of these lenses either failed to move beyond the drawing board or achieve long-term operation.

An early proposal made in 1759 by a London optician involved grinding the glass of the lantern windows at the Eddystone Lighthouse to form lenses 15 feet in diameter. The proposal was deemed impractical, however, because the considerable thickness of the lenses resulted in a significant portion of the emitted light being absorbed.

In the late 1780s, glasscutter Thomas Rogers started developing glass lenses and reflectors that were used in lighthouses across the United Kingdom. However, his poor oversight of the glass fabrication process and management of the lighthouses led to his services being gradually terminated.

Finally, in the early 1800s, Englishman George Robinson designed some small half-sphere lenses for two lighthouses. But each lens was made from green bottle glass with many bubbles and striae that interfered with the light, and it was quickly discovered that the polished metal reflectors were more powerful without the lenses, leading to the lenses’ removal.

Fresnel lens: A revolution in lighthouse lighting technology

Though impossible to give a precise number, the Fresnel lens is frequently called “the invention that saved a million ships” due to its greatly enhanced lighting capabilities, which extended the reach of lighthouse beams from 8–12 miles to more than 20 miles away from shore.

The Fresnel lens was developed by French civil engineer and physicist Augustin-Jean Fresnel. In 1819, he proposed to the French Commission for Lighthouses that he would conduct a systematic review of possible improvements in lighthouse illumination. His proposal was approved, and he quickly produced his first report on optics and lamps for lighthouses just two months after starting the project.

His report showed that up until then, excessive thickness and weight as well as poor quality had prevented the success of glass lenses in lighthouses. He believed that if these limiting factors were overcome, glass lenses could replace polished metal reflectors.

To solve the thickness and weight problem, Fresnel used his wave theory of light to design lenses that unintentionally paralleled earlier work by French naturalist, mathematician, and cosmologist Georges-Louis Leclerc, Count of Buffon and French philosopher, political economist, politician, and mathematician Marie Jean Antoine Nicolas de Caritat, Marquis of Condorcet. (He was informed of the similarity after submitting his design.)

As described in an article by the United States Lighthouse Society, Fresnel’s design used thin bull’s eye-shaped panels, which refracted the light both horizontally and vertically, producing a much stronger beam of light. It required hundreds of glass pieces to be specially cut and placed to surround the illuminant.

Credit: David Willey, YouTube

Fresnel’s original design relied on fixed panels, but he later added a set of revolving panels so that unique flash patterns could be employed to distinguish between different lighthouses. Colored panels also could be used to further differentiate between lighthouses.

Fresnel finished his design in 1825, and it quickly found application in lighthouses across France. Other countries across Europe adopted the design swiftly as well, but the U.S. was slower to adopt Fresnel lenses due to disagreements over the cost. However, by the 1860s, the U.S. had fit all its lighthouses with Fresnel lenses.

As the use of Fresnel lenses spread around the world, the lenses evolved to be offered in several sizes, with the largest (called the Hyper-radial) having a focal length of 1,330 mm and the smallest (called the Eighth Order) having a focal length of 75 mm. The Fourth Order Fresnel lens, with a focal length of 250 mm, was the most commonly used lens in lighthouses because it was considered a good balance between range and size for various coastal and harbor applications.

From maritime to cultural beacon

Thanks to the many lives saved by the superior lighting capabilities of the Fresnel lens, this maritime beacon now serves as a cultural beacon for the maritime industry. Its enduring legacy also makes surprising appearances in pop culture, such as the 2019 film The Lighthouse.

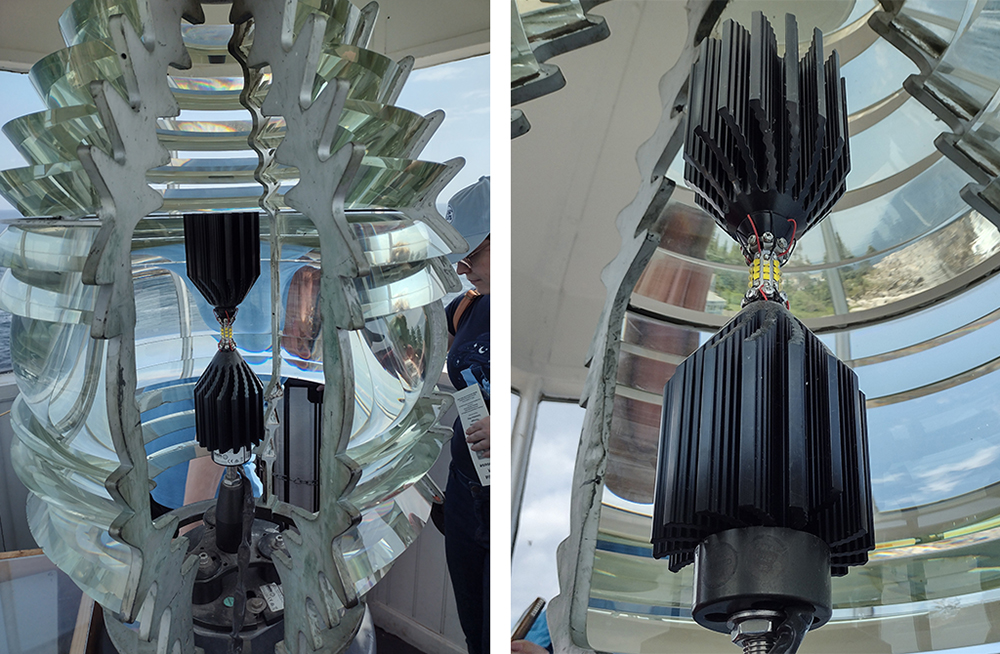

Despite its lasting status as a symbol of hope and safety, in the 1960s, many traditional glass-based Fresnel lenses started being replaced with more modern lighting technology, including acrylic lenses, aerobeacons, and VRB-25 lights. Fortunately, some Fresnel lenses remain in use, albeit with some design changes. For example, the illuminant at the core of the Fresnel lens is now often more environmentally friendly options, such as LEDs. Modern lighthouses also increasingly incorporate solar panels, allowing them to harness renewable energy and operate independently of the electrical grid.

In 2020, the United States Coast Guard replaced the traditional incandescent light source in the Pemaquid Point Light Fresnel lens with a high-output LED. The above photos show close-ups of the updated design. Credit: Don McDonald

Fresnel lenses also find uses outside lighthouses, such as background lighting in photography and cinema and to concentrate sunlight for solar heating applications. So even if, like me, you live far away from the coast, you may have the chance to see these lenses that played such a significant role in the maritime industry up close and personal.

Author

Lisa McDonald

CTT Categories

- Education

- Glass

- Optics

- Transportation

Related Posts

Sports-quality ice: From pond side to precision Olympic engineering

February 12, 2026