A University of Dayton research team – led by Liming Dai, UD’s Wright Brothers Institute endowed chair in nanomaterials – says it has developed a technique that makes carbon nanotubes a cheaper and better fuel cell catalyst than platinum.

The Feb. 6th online edition of Science magazine reports on the team’s findings. Since that announcement, interviews with Dai – a professor of materials engineering in UD’s Department of Chemical and Materials Engineering – also have appeared in online science-community websites and in print trade magazines.

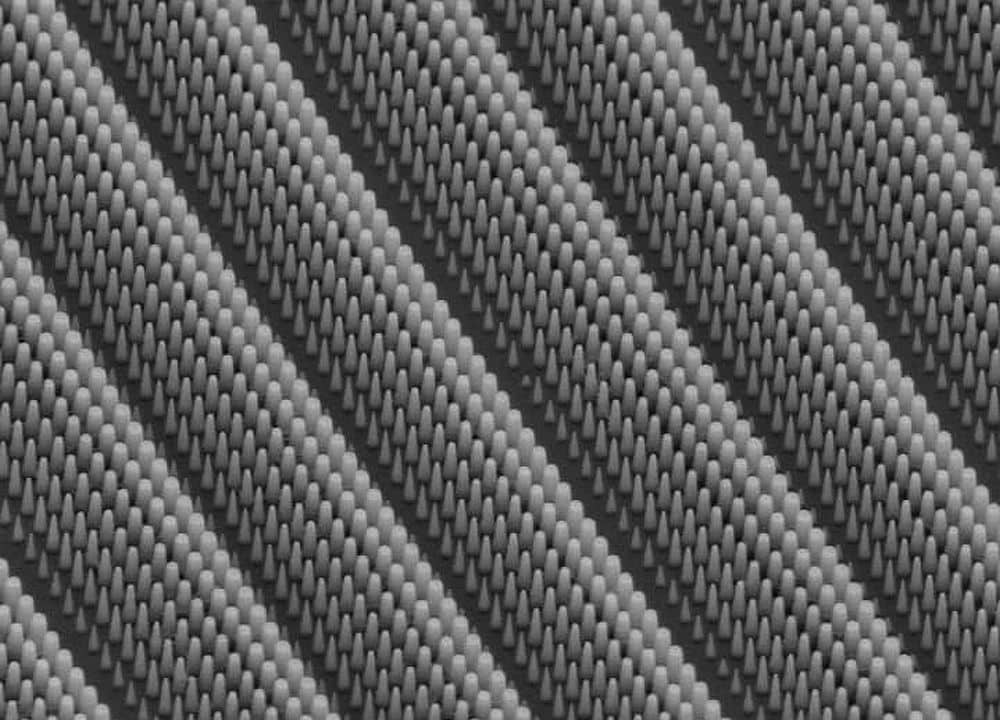

As reported, Dai’s team has shown that vertically-grown arrays of carbon nanotubes act as effectively as platinum in alkaline fuel cells if – and this is key – the carbon nanotubes are doped with nitrogen.

Reporter Stephen Battersby explains the need for nitrogen in NewScientist:

Unaided, this reaction would happen only very slowly, so the cathode has to be formed of a chemical catalyst to speed up the reaction. Traditionally, the only substance that has worked well enough is platinum.

Battersby notes, when carbon nanotubes were used without nitrogen doping in earlier experiments, they catalyzed fuel cell action but “were much less effective than platinum nanoparticles.”

Dai reveals his methodology in a Feb. 5 article in Technology Review. The first step, he says, is starting with a compound comprised of carbon, nitrogen and iron. The next step is placing the compound on a quartz substrate and “heating it in the presence of ammonia, resulting in nitrogen-doped carbon nanotubes growing straight up from the surface.”

Then any latent iron needs to be eliminated by oxidizing the array and moving it to a polymer film. The electrode is then emerged in a potassium hydroxide electrolyte.

It was at this point, Dai says, when his team noticed the technology’s ability to speed up the cathode reaction of oxygen and electrons.

In Dai’s estimation, carbon nanotubes doped with nitrogen “are even better than platinum.” He says they produce four times as much electric current as platinum and “where platinum nanoparticles can lose their effectiveness when they cluster together or become tainted by carbon monoxide, the nanotubes are immune to these degradations.”

Dai believes his team may be able to produce the same results using other forms of nitrogen-doped carbon. “Now we have discovered how this chemistry works,” he points out, “It may not be necessary to use nanotubes.”

CTT Categories

- Material Innovations

- Nanomaterials

- Transportation

Related Posts

Sports-quality ice: From pond side to precision Olympic engineering

February 12, 2026