[Image above] Credit: Drexel University

Although it’s pretty to watch from the cozy warmth of your home, one of the biggest hazards of the winter months is the quickly falling snow that accumulates on roads, causing numerous traffic accidents and fatalities. And the second biggest winter hazard is the salt that is dumped on the road to melt said snow.

According to the Cary Institute, between 10 and 20 million tons of road salt are spread on U.S. highways each winter. And while road salt solves the snow buildup, it wreaks havoc on the environment, especially water quality, when it eventually leaches into groundwater, rivers, and other bodies of water over time. It also destroys vegetation, not to mention vehicles and the surfaces on which the salt is deposited.

But we’ve been using the stuff to melt snow since the late 1930s. And for years it’s worked relatively well, even though other alternatives such as pickle brine and beet juice have been suggested as effective substitutes. But nothing has worked as well as good old NaCl.

Several years ago, an engineer came up with an idea for solar powered smart roads made of glass and solar panels that would use the sun’s energy to melt snow. Last year we reported on research where scientists incorporated steel fibers and carbon particles into concrete that could conduct enough electricity to melt snow and ice.

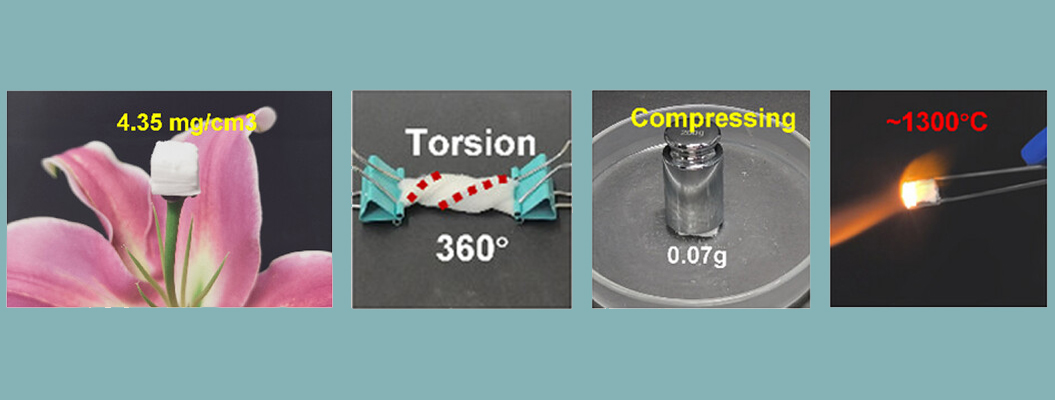

Researchers at Drexel University—in collaboration with Purdue University and Oregon State University—are currently experimenting with a different approach to making streets safer after the onslaught of snow and ice. Led by Yaghoob Farnam, assistant professor at Drexel’s College of Engineering, the team successfully demonstrated that paraffin wax added to concrete can melt snow within a 25-hour testing period.

Paraffin wax is a phase change material—which means it can absorb and release heat during the melting and freezing process. That makes it an ideal material to use in applications for melting snow or ice. It is also environmentally friendly, inexpensive, and chemically stable, according to a Drexel news release.

“Phase change materials can be incorporated into concrete using porous lightweight aggregate or embedded pipes, and when a phase change material transforms from liquid to solid during cooling events, it can release thermal heat that can be used to melt ice and snow,” Farnam says in the release.

The team tested paraffin in two different temperature environments on concrete samples that were sealed in an insulated container: one containing metal pipes filled with paraffin, one that contained a paraffin-infused lightweight porous aggregate, and a reference sample without paraffin. They piled five inches of snow on top of each sample.

In the first test, the temperature inside the containers was held to 35–44ºF. Both concrete samples containing paraffin melted the snow within 25 hours. For the second test, the researchers kept the inside air temperature of the containers at freezing level, 32ºF, prior to adding snow. The sample containing paraffin-infused aggregate melted the snow more efficiently than the metal pipes filled with paraffin—essentially because of the freezing delay brought about by various pore sizes, which enable heat energy to be released over a longer time period.

Credit: Drexel University; YouTube

“The gradual heat release due to the different pore sizes in porous lightweight aggregate is more beneficial in melting snow when concrete is exposed to variety of temperature changes when snow melting or deicing is needed,” Farnam explains in the release. He says airports could be the first beneficiaries of the technology due to the ongoing challenges they have with snow during the winter.

Although he notes their findings require further research, the discovery could be useful not only for airports and roads, but also communities in colder climates where snow and ice are common impediments to walking and driving.

“Eventually this could be used to reduce the amount of deicing chemicals we use or can be used as a new deicing method to improve the safety of roads and bridges,” Farnam adds. “But before it can be incorporated, we will need to better understand how it affects durability of concrete pavement, skid resistance, and long-term stability.”

The team’s paper, published in Cement and Concrete Composites, is “Incorporating phase change materials in concrete pavement to melt snow and ice” (DOI: 10.1016/j.cemconcomp.2017.09.002).

Did you find this article interesting? Subscribe to the Ceramic Tech Today newsletter to continue to read more articles about the latest news in the ceramic and glass industry! Visit this link to get started.

Author

Faye Oney

CTT Categories

- Basic Science

- Cement

- Environment

- Material Innovations