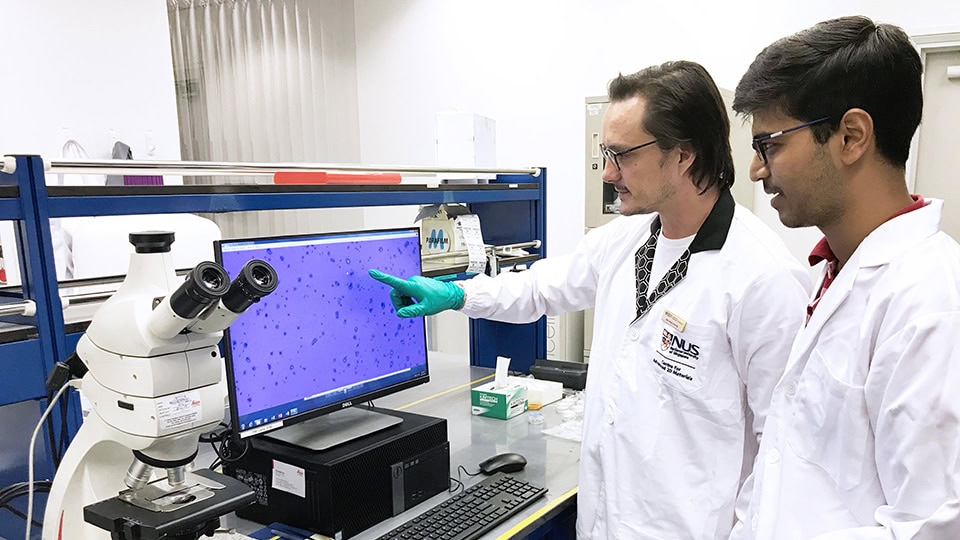

[Image above] Researchers inspect graphene samples at the NUS Centre for Advanced 2D Materials. Credit: NUS Centre for Advanced 2D Materials

When it comes to sourcing graphene for research, we have two words of advice: caveat emptor.

Graphene is a strong material measuring just one atom thick, with excellent heat- and electrical-conducting properties. Although McKinsey predicts a $70 billion market for graphene semiconductors by 2030, the material still has its challenges in commercialization, especially in using mass quantities of it in manufacturing.

If you currently work with graphene in your research, it is probably purchased in good faith from a reliable supplier.

However, where you source your graphene could have an impact on your research results. Scientists from RMIT University recently published a study that found samples of commercial-grade graphene were contaminated by silicon.

“We found high levels of silicon contamination in commercially available graphene, with massive impacts on the material’s performance,” RMIT vice chancellor research fellow Dorna Esrafilzadeh explains in a ScienceDaily news release.

Esrafilzadeh and Rouhollkah Ali Jalili led a team to examine commercial-grade graphene samples at the atomic level, using transition electron microscopy. They found silicon, the raw material that is supposed to be removed during the production of graphene, present in many of the samples. “We believe this contamination is at the heart of many seemingly inconsistent reports on the properties of graphene and perhaps many other atomically thin two-dimensional materials,” she adds.

Esrafilzadeh and Jalili not only inspected and identified the substandard graphene samples, they also tested the samples for purity and performance. The researchers found the contaminated graphene performed up to 50 percent worse when tested as electrodes, compared to pure graphene they used in similar tests, according to the release.

The open-access paper, published in Nature Communications, is “Silicon as a ubiquitous contaminant in graphene derivatives with significant impact on device performance” (DOI: 10.1038/s41467-018-07396-3).

Identifying the flakes from the fakes

Esrafilzadeh’s and Jalili’s research comes on the heels of another study that puts inferior graphene under the microscope, so to speak.

Researchers from the National University of Singapore (NUS) analyzed graphene samples from more than 60 suppliers from countries in the Americas, Asia, and Europe. They initially wanted to create a reliable method for determining the quality of graphene samples from all over the world.

They discovered that the majority of the samples consisted primarily of graphite powder—the stuff from which graphene is exfoliated, according to an NUS news release. The samples contained less than 10 percent of pure graphene flakes.

Director of the NUS Centre for Advanced 2D Materials and leader of the study Antonio Castro Neto and his team also discovered that some of the samples were contaminated with chemicals used in producing graphene, tainting the product even further.

“Whether producers of the counterfeit graphene are aware of the poor quality is unclear,” Castro Neto explains in the release. “Regardless, the lack of standards for graphene production gives rise to bad quality of the material sold in the open market. This has been stalling the development of the future applications.”

In other words, if the results of your research do not meet expectations, inferior graphene may be to blame.

Castro Neto believes that standards need to be set for graphene, or researchers are just wasting time and money to get inaccurate results.

“We hope that our results will speed up the process of standardization of graphene within [the International Organization for Standardisation] as there is a huge market need for that,” Castro Neto adds. “This will urge graphene producers worldwide to improve their methods to produce a better, properly characterized product that could help to develop real-world applications.”

The paper, published in Advanced Materials, is “The Worldwide Graphene Flake Production” (DOI: 10.1002/adma.201803784).

Author

Faye Oney