[Image above] Credit: metamorworks / Shutterstock

Among the many changes brought by the Industrial Revolution, the increased pace of production has molded every aspect of our lives around being “fast”: fast fashion, fast food, fast transport. Although there is a rising social movement to adopt a “slow living” lifestyle to combat the burnout of hustle culture, many of our technological developments still center around increasing the speed and efficiency of operations.

Hypersonic flight is the poster child for this “fast” mentality. It refers to flight at speeds greater than Mach 5 (five times the speed of sound), and hypersonic vehicles are expected to offer significant advantages in both future military and potentially commercial applications due to their unparalleled speed, agility, and ability to bypass conventional defense systems.

However, moving at such high speeds comes with a host of technological challenges due to the extreme environmental conditions that materials must be able to withstand. The first military hypersonic flight programs tried to surmount the physics of extreme heat, plasma-induced communications blackouts, and maneuverability by focusing largely on refined flight paths (cruise vs glide systems) and accurate sensing technology (e.g., gyroscopes) for navigation. More recent developments focus largely on the materials aspect of hypersonic vehicles, such as hardened electronics and plasma-resistant optics, to withstand the forces that are still present in the optimized flight conditions.

This CTT takes a broad look at some recent breakthroughs in the development of advanced ceramic materials for hypersonic flight. But first, let us look at the environmental factors shaping these developments.

Core challenges of hypersonic flight

Our Earth, with its delicate but breathable oxygen atmosphere and persistent gravity, makes moving really fast challenging. Specifically, there are four main obstacles to hypersonic flight, all of which require advanced material solutions.

1. The thermal barrier (extreme heat)

At speeds above Mach 5 (3,836 miles/hour or 6,174 km/hour), vehicles encounter extreme friction and aerodynamic heating. At Mach 10+, the air in front of a vehicle cannot move out of the way fast enough, creating a massive shockwave. Under these extreme kinetic energy conditions, air molecules break apart and ionize, turning the atmosphere into a glowing shroud of plasma.

This plasma is hot enough to melt even nickel-based superalloys, so early hypersonic research relied on ablative coatings that charred and broke off to carry heat away from the vehicle. Although these coatings were effective for one-time reentry, they were less ideal for maneuverable, reusable flight vehicles because they change the vehicle’s shape as they melt.

2. Chemical erosion (oxidation)

At Mach 5+, the air not only gets hot but also becomes chemically aggressive. The thermal barrier is the cause, and oxidation is the mechanism. The massive shockwave in front of the vehicle rips oxygen molecules (O2) apart into atomic oxygen, like a dog with a stuffed toy. These single atoms are hyperreactive and attack the vehicle’s surface, causing a process called recession.

Unlike rusting, which is a slow oxidation process, hypersonic oxidation involves violent, high-speed erosion. If the structural material is not protected, it may undergo a phase change into a gas and simply blow away. This process changes the vehicle’s shape in midflight. The challenge for ceramics, then, is not just surviving the heat but also creating a skin that keeps oxygen from eating the vehicle from the outside in.

3. Plasma blackout (communication)

The induced plasma caused by the extreme temperature and pressure forms a conductive layer (sheath) around the vehicle. Plasma reflects most radio waves, and so the sheath causes a communications blackout that prevents the vehicle from receiving global positioning system updates or steering commands. As a result, the vehicle flies blind and deaf during its hottest phase.

4. Maneuverability and precision (flying blind and deaf)

Steering at hypersonic speeds is like trying to turn a car on ice at 200 miles/hour (320 km/hour). Slight adjustments to the control surfaces (i.e., the fins) create massive mechanical stresses. The stiffness provided by ceramics gives the vehicle’s fins rigidity under this massive stress.

These four obstacles often work together to create synergistic challenges. For example, even a slight change in the sharpness of a wing edge or nose cone due to oxidation or melting can cause the vehicle to lose lift or veer miles off target. If the vehicle is unable to communicate with a control station, the situation can become dangerous quickly. These issues are actively being researched, and innovative materials and manufacturing methods are being developed to address them.

Developments in UHTC manufacturing: 3D printing and PDCs

Ultrahigh-temperature ceramics (UHTCs) are a leading class of materials being developed for hypersonic applications. Historically, the biggest drawback to UHTCs wasn’t their performance but processing difficulties. Traditional manufacturing involves hot pressing or spark plasma sintering ceramic powders under immense heat and pressure for hours (even days) to create blocks that then are painstakingly (and expensively) carved into shape.

Matthew Thompson, a materials engineering doctoral candidate at Purdue University, loads a crucible into a box furnace to heat and remove binders from 3D-printed ceramic samples. Credit: Charles Jischke, Purdue University

In the past few years, researchers have investigated proprietary resin systems, surface treatments, and other approaches to enable 3D printing of UHTCs, such as the dark ceramic boron carbide. Dark ceramic materials absorb the ultraviolet light used in digital light processing 3D printers, preventing the printed material from curing properly. Using ceramic-resin slurries, a team at Purdue University grew complex geometries that would have been physically impossible to carve or mold.

Although additive manufacturing allows for complex shapes, the material chemistry must also evolve. Enter: polymer-derived ceramics (PDCs). PDCs are ideal candidates for hypersonic materials because they can be molded into complex shapes as preceramic polymers before being pyrolyzed (converted through heating) into ceramics.

Recently, two researchers from The University of Texas at Arlington used a machine-learning interatomic potential (MLIP) trained on density functional theory (DFT) data to simulate processing for a polymer-derived silicon–carbon–nitrogen–hydrogen system, tracking the ceramic network’s evolution during the polymer-to-ceramic transition.

Another recent PDC development involves an innovative selective laser reaction pyrolysis (SLRP) technique that researchers from North Carolina State University used to synthesize the UHTC hafnium carbide. Instead of a furnace, they used a 120-watt laser to transform liquid polymer precursors into solid hafnium carbide coatings in a single step, in open air, in a matter of seconds.

Moving away from energy-intensive furnace sintering to localized, rapid fabrication drastically reduces the carbon footprint of manufacturing. Additionally, the physical molds in traditional hot pressing limit the possible shapes. The innovative laser technique prints the ceramic into existence without a mold, enabling complex shapes similar to other additive manufacturing methods.

Machine learning applications for hypersonic material development

Using machine learning methods to create quantum-accurate maps of the UHTC synthesis process can enable rapid manufacturing techniques such as SLRP. Researchers can therefore ensure that speed does not come at the cost of structural integrity.

DFT is foundational to materials synthesis, but it is computationally expensive. Machine learning methods such as MLIP achieve DFT-level accuracy at a fraction of the computational cost, thus enabling rapid artificial intelligence-driven design and stress testing of thousands of chemical variations or geometric configurations rather than relying on slow, expensive trial-and-error testing.

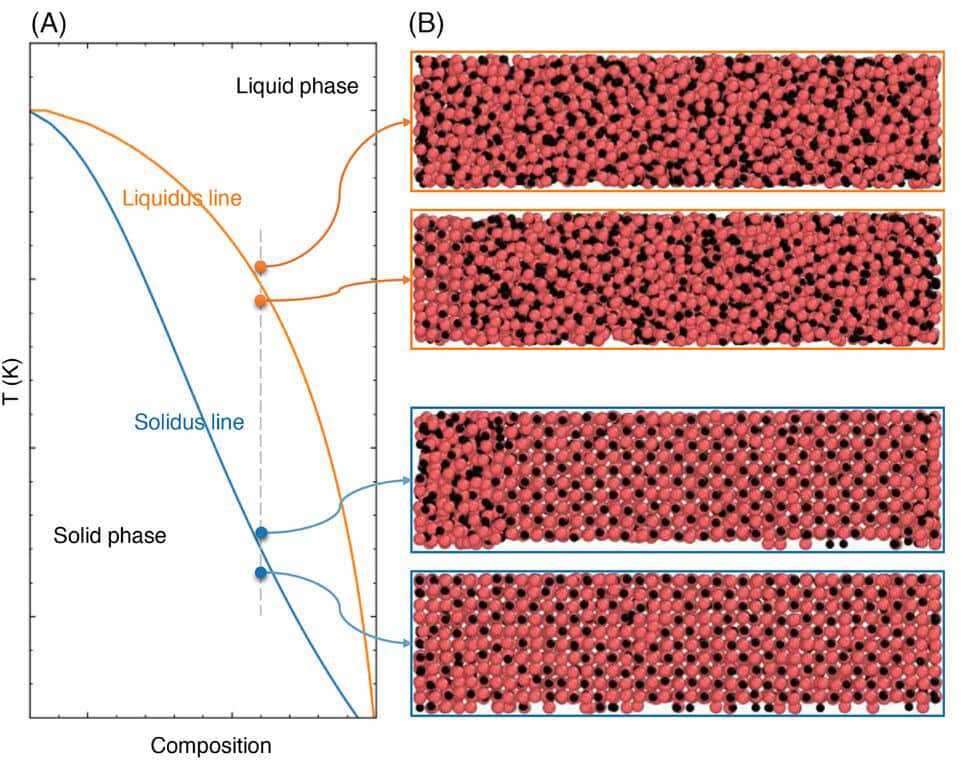

(A) Schematic representation of a binary phase diagram, illustrating the solidus and liquidus lines. (B) The equilibrium state of a material at various temperatures for a specific composition. Large points represent metals while small points denote carbon. Credit: Dai et al., Journal of the American Ceramic Society

Recently, researchers from the University of Science and Technology Beijing and the Aerospace Research Institute of Materials & Processing used MLIP simulations to identify a new melting point record of 4431 K (~4,158°C or ~7,516°F) within the hafnium–tantalum–carbon–nitrogen system. By applying high-accuracy DFT and a critical equilibrium method, the researchers determined that nitrogen alloying elevates the melting point by increasing the enthalpy of melting and reducing the entropy of the liquid phase. These findings provide a computational framework for designing UHTCs for extreme environments.

Hybrid ceramic composites

Today, the leading edges of hypersonic vehicles (nose cones and wing edges) are made from UHTCs, ceramic matrix composites, or carbon–carbon composites. Although these materials can withstand temperatures exceeding 2,000°C, they are traditionally brittle and notoriously difficult to manufacture and integrate into a hypersonic vehicle’s metallic frame.

Recent research by Imperial College London scientists addresses this integration. This work focused on combining porous and dense zirconium diboride (ZrB2) to enable transpiration cooling and provide structural integrity, respectively, during hypersonic flight. Introducing a cool layer of gas through the porous ceramic skin creates a buffer against the hot plasma shroud.

The Imperial College London researchers developed a brazing method to join the ZrB2 to zirconium metal. The thermal expansion coefficients of the two materials are nearly identical, meaning that the joint remains stable even as the vehicle undergoes massive thermal cycling.

Messy chemistry for the win

Although manufacturing is getting faster, the chemistry is getting messier—in a good way. As someone who loved mixing all sorts of household chemicals in my parents’ bathroom sink, messy chemistry appeals to me.

For our purposes, messy chemistry means high-entropy ceramics. Traditional ceramics are simple, containing few elements. High-entropy ceramics, conversely, mix five or more elements into a single crystal structure. This chaos paradoxically creates a more stable material.

A particularly exciting high-entropy ceramic developed by researchers at The Pennsylvania State University is 9-cation porous high-entropy diboride (9PHEB). This material has ultrahigh compressive strength up to 2,000°C while remaining lightweight due to its 50% porosity. This pioneering material may solve the weight vs. heat resistance trade-off in shielding for hypersonic vehicles.

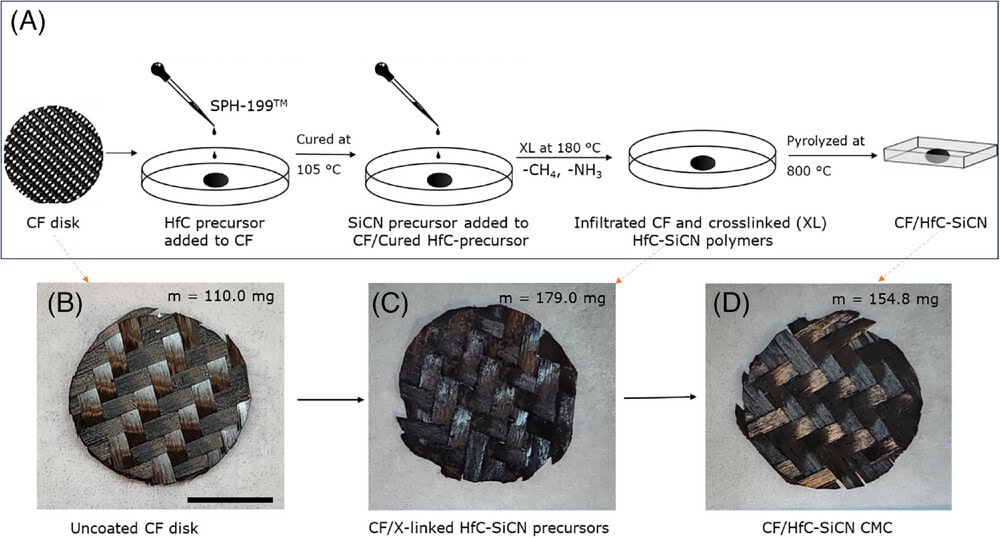

Fiber-reinforced composites are another way to improve the properties of UHTCs. Researchers from Kansas State University developed a PDC hybrid matrix of hafnium carbide (HfC) and silicon carbonitride (SiCN) to improve the oxidation resistance of carbon fiber-reinforced minicomposites. The hybrid HfC–SiCN matrix forms a protective, multilayered oxide that significantly slows the degradation of the underlying carbon fibers compared to single-component matrices. This hybridization approach enhances the structural integrity and longevity of ceramic matrix composites for use in hypersonic and aerospace applications.

(A) Schematics show coating, cross-linking, and pyrolysis process of carbon fiber (CF)/HfC–SiCN ceramic matrix composites (CMCs). Digital camera images of (B) typical CF disk sample and (C and D) CF-reinforced HfC–SiCN disks after curing (cross-linked) and pyrolysis. Scale bar is 10 mm. Credit: Mujib et al., International Journal of Ceramic Engineering & Science (CC BY 4.0)

An emerging hypersonic research area involves self-healing UHTCs. When a microcrack forms due to thermal stress, healing agents such as tantalum silicide react with the incoming oxygen to form a liquid glass that flows into the crack and solidifies, thereby sealing it. An open-access study by Northwestern Polytechnical University researchers on HfB2–SiC–TaSi2 coatings showed that this self-repair mechanism can happen at temperatures above 2,000°C, allowing a vehicle to repair its thermal shield during flight.

Protecting the core

The survival of a hypersonic vehicle’s core depends on its exterior skin because of the threat of oxidation. So, Sejong University researchers proposed a numerical model to predict the oxidation behavior of silicon carbide coatings used in thermal protection systems for hypersonic vehicles.

By integrating a Gibbs free energy minimization solver into an open-source porous material analysis toolbox, the researchers successfully simulated the chemical equilibrium between the atmospheric flow and the ceramic surface. This success allowed the material recession and surface temperature changes to be calculated under high-enthalpy conditions. Ultimately, this computational approach provides an initial evaluation of the durability of silicon carbide coatings in hypersonic environments without extensive experimental testing.

Traditional coatings used for heat shields can sometimes be porous or grow in fragile, column-like structures that crack easily under the stress of hypersonic flight. To overcome this limitation, researchers at The Pennsylvania State University developed a specialized spraying technique called high-power impulse magnetron sputtering, which uses high-power electrical pulses to turn metal into a mist of charged particles. The result is a dense, smooth film coating that is harder than single-crystal silicon carbide.

The path forward

We can now print ceramic matrix composites and simulate the melting points of UHTCs, but in some cases, these advanced materials have surpassed our ability to accurately measure their properties. So, researchers must develop improved measurement techniques (metrology) to accurately test novel advanced ceramic materials, which will pay dividends beyond the field of hypersonics. (Consider how previous military-driven research studies led to surprising large-scale impacts on the commercial sector, such as canned food and disposable sanitary napkins.)

The journey from the lab to the leading edge is becoming an increasingly faster process thanks to computer-aided design and testing protocols, but a material is only as good as the people who can build with it. The recent extension of the ACerS–USACA Hypersonic Materials Training Program is a critical step in building the manufacturing capability for these innovative materials and technologies.

By combining next-generation fabrication methods, novel material compositions, and AI-driven modeling, the research highlighted here has moved us closer to a world where hypersonic flight is not just a military milestone but a standard for the future of global transit.

Learn about more advanced ceramic developments for hypersonic applications in the ACerS journals.

Author

Becky Stewart

CTT Categories

- Aeronautics & Space

- Manufacturing