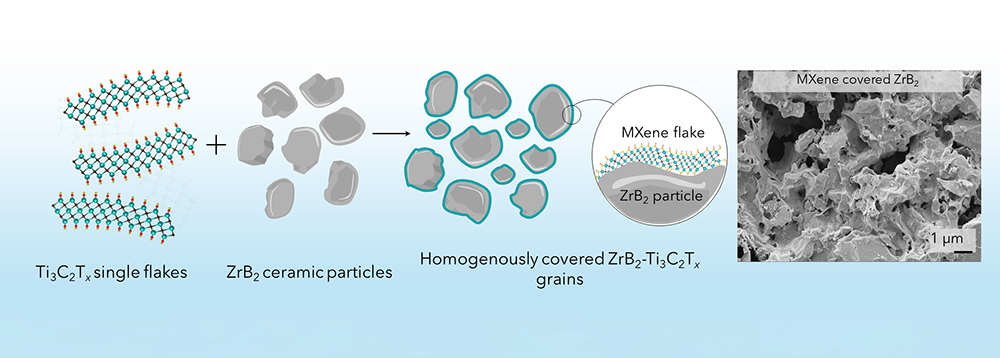

[Image above] Illustration of how electrons pair together in a superconducting material. Credit: Greg Stewart, SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory

In 1908, Dutch physicist Heike Kamerlingh Onnes made a pivotal discovery in the field of low-temperature physics: the liquification of helium. Over the next few years, his continued work in this area at the University of Leiden resulted in him receiving the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1913.

Among his findings, in 1911, Onnes discovered that the electrical resistance of mercury completely disappeared at temperatures just a few degrees above absolute zero. This phenomenon of zero electrical resistance at very low temperatures became known as superconductivity.

For a material to superconduct, electrons must become paired, and these pairs must be coherent (show synchronized movements). If electrons are paired but incoherent, the material may end up being an insulator because the unsynchronized movements hinder current flow.

For some materials such as mercury, cryogenic temperatures close to absolute zero (-273.15°C or -460°F) are required for electrons to pair and achieve the superconducting state. Other low-temperature superconductor (LTS) materials include lead, niobium, niobium-titanium, niobium-tin, and lead-bismuth. Niobium-titanium is currently used for magnetic resonance imaging in hospitals.

On the other hand, certain compositions of cuprates (copper oxide compounds) are considered high-temperature superconductor (HTS) materials because they can support current and magnetic fields at temperatures at least an order of magnitude higher than LTS materials (up to about 130 K, or -143.1°C or -225.67°F, at ambient pressure). Potential HTS applications include transmission cables, fault current limiters, transformers, and magnetic levitation systems for trains.

Since Onnes was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1913, several other Nobel Prizes related to superconductivity have been awarded:

- 1972: John Bardeen (University of Illinois), Leon N. Cooper (Brown University), and Robert Schrieffer (University of Pennsylvania) for their first microscopic theory of superconductivity since 1911.

- 1973: Leo Esaki (IBM Thomas J. Watson Research Center) and Ivar Giaever (General Electric Company) for their experimental discoveries regarding tunneling phenomena in semiconductors and superconductors, respectively.

- 1987: Georg Bednorz and K. Alex Müller, both from IBM Zurich Research Laboratory, for their discovery of superconductivity in ceramic materials, specifically copper oxide with lanthanum and barium additives (known as cuprates).

- 2003: Alexei A. Abrikosov (Argonne National Laboratory), Vitaly L. Ginzburg (P.N. Lebedev Physical Institute), and Anthony J. Leggett (University of Illinois-Urbana) for their work on the theory of superconductors and superfluids.

Despite these advancements, the “holy grail” of room-temperature superconductivity remains out of reach. If superconductivity occurred at ambient temperatures and pressures, it would enable the creation of significantly smaller and more efficient electronic circuits, with a corresponding reduction in price.

However, researchers are hopeful that comparing different types of HTS materials may offer clues to unlocking higher temperature superconductivity.

Superconductivity insights enabled by HTS materials

Nickel-based versus copper-based superconductors

While most HTS materials are cuprates, some nickelates (nickel oxide compounds) are HTS materials, too. Researchers suspected that some nickel compounds may behave as HTS materials because nickel is near copper on the periodic table. This hypothesis led to researchers at SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory and Stanford University developing a nickel-based superconductor in 2019.

In April 2023, Brookhaven National Laboratory announced the results of some experiments conducted on its National Synchrotron Light Source-II that revealed similarities and differences between nickel-based and copper-based high-temperature superconductors. In both materials, the magnetic interactions between copper or nickel and oxygen ions played a role in electron movement, but the magnetic interactions among nickel atoms were slightly weaker.

Additionally, the charge density wave—where electrons form a wave-like pattern that can result in a nonuniform distribution of charge in the crystal lattice—was also studied. In the HTS nickelate, this wave depended on interactions among all different elements, whereas the HTS cuprate’s wave depended only on the interactions between copper and oxygen ions.

“These findings indicate that the nickel compounds are promising to learn more about how the cuprates work, and they indicate the different ways you might want to change the nickel compounds to make them more like the cuprates—to have stronger magnetism or stronger superconductivity,” says Jennifer Sears, postdoctoral researcher at Brookhaven, in a Brookhaven press release.

The first open-access paper, published March 2022 in Physical Review X, is “Role of oxygen states in the low valence nickelate La4Ni3O8” (10.1103/PhysRevX.12.011055).

The second open-access paper, published February 2023 in Physical Review X, is “Electronic character of charge order in square-planar low-valence nickelates” (DOI: 10.1103/PhysRevX.13.011021).

N-type superconductors

In 1989, the first n-type superconductor was discovered. In contrast to traditional p-type superconductors, in which the charge carriers are electron vacancies or holes, the charge carriers in n-type superconductors are electrons.

Researchers have gained useful insights into the role of electronic structure in superconductivity by comparing p-type and n-type superconductors. For example, typically, superconductivity can be achieved at higher temperatures in p-type superconductors rather than n-type superconductors.

In August 2024, researchers from SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory, Stanford University, and other institutions observed that electron pairing, required for achieving superconductivity, can occur at much higher temperatures in n-type superconductors than previously thought, and in an unexpected material—an antiferromagnetic insulator.

The extremely underdoped cuprate family Nd2-xCexCuO4 (NCCO) has not been deeply studied because its maximum superconducting temperature is relatively low—25 Kelvin (-248.2°C or -414.7°F)—compared to other cuprates. Furthermore, most members of this cuprate family are good insulators, according to a SLAC press release.

However, using angle-resolved photoemission spectroscopy and high-quality single crystals, the researchers observed an anomalous normal-state energy gap in NCCO. This gap, which was an order of magnitude smaller than the antiferromagnetic gap, showed strong resemblance to a superconducting gap based on shape and sharpness.

The researchers believe this normal-state gap in the underdoped n-type cuprates originated from incoherent Cooper pairing of electrons, and this gap persisted up to about 140 K (-133°C or -207°F), which is much higher than the zero-resistance state of 25 K. Surprisingly, this study found that the Cooper pairing was strongest among the most insulating samples.

For compositions where x = 0.11, this gap became undetectable at temperatures around 50 K (-223.15°C or -369.67°F), which coincided with a minimum resistivity measurement. The resistivity increased as the temperature dropped below 50 K, which was attributed to a depletion of unpaired carriers.

These findings suggest that “the lack of higher-Tc superconductivity in n-type cuprates is primarily attributable to the limited mobility of Cooper pairs,” the researchers write in the paper.

So, though NCCO may not be the material to reach superconductivity at room temperature, the findings “suggest the potential for high-temperature [n-type] superconductivity comparable to the maximum transition temperatures observed in the p-type cuprates,” the researchers write.

In a SLAC press release, senior author Zhi-Xun Shen, Stanford professor and investigator with the Stanford Institute for Materials and Energy Sciences at SLAC, says their findings open a “potentially rich new path forward,” and they plan to conduct more experiments on this incoherent pairing state. Ideally, they will find ways to manipulate the materials to “perhaps coerce these incoherent pairs into synchronization,” he says.

The open-access paper, published in Science, is “Anomalous normal-state gap in an electron-doped cuprate” (DOI: 10.1126/science.adk4792).

Author

Laurel Sheppard

CTT Categories

- Basic Science

- Electronics

- Material Innovations