[Image above] Credit: Massachusetts Institute of Technology

Ever since someone got the idea to bottle and market drinking water in plastic single-serving containers, it’s been the bane of planet Earth’s existence. Earlier this year, National Geographic reported that of the 8.3 billion metric tons of plastic that end up as trash (and ultimately in landfills), only 9% is recycled.

But plastic is just one of many of our planet’s adversaries. According to the National Precast Concrete Association, cement manufacturing accounts for 5% of CO2 emissions globally. A report from the International Energy Agency finds that cement production accounts for 70–80% of all energy use in non-metallic minerals production (page 139).

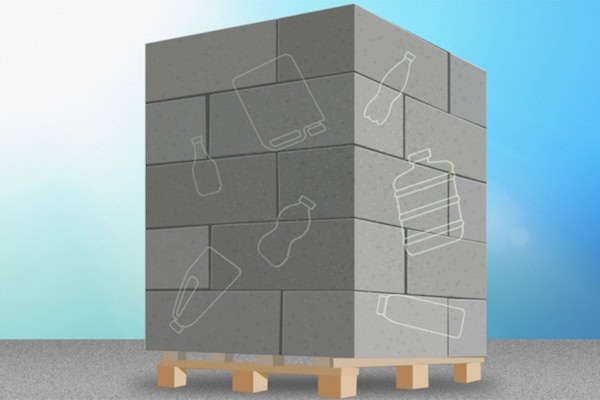

Students at Massachusetts Institute of Technology appear to have solved both problems. They have come up with a way to incorporate irradiated plastic into cement paste to make concrete that is nearly 15% stronger than what’s available today. And more importantly, if the irradiated plastic replaces a small portion of concrete, it could significantly reduce concrete’s carbon footprint at scale.

“There is a huge amount of plastic that is landfilled every year,” assistant professor in MIT’s Department of Nuclear Science and Engineering Michael Short explains in an MIT news release. “Our technology takes plastic out of the landfill, locks it up in concrete, and also uses less cement to make the concrete, which makes fewer carbon dioxide emissions.”

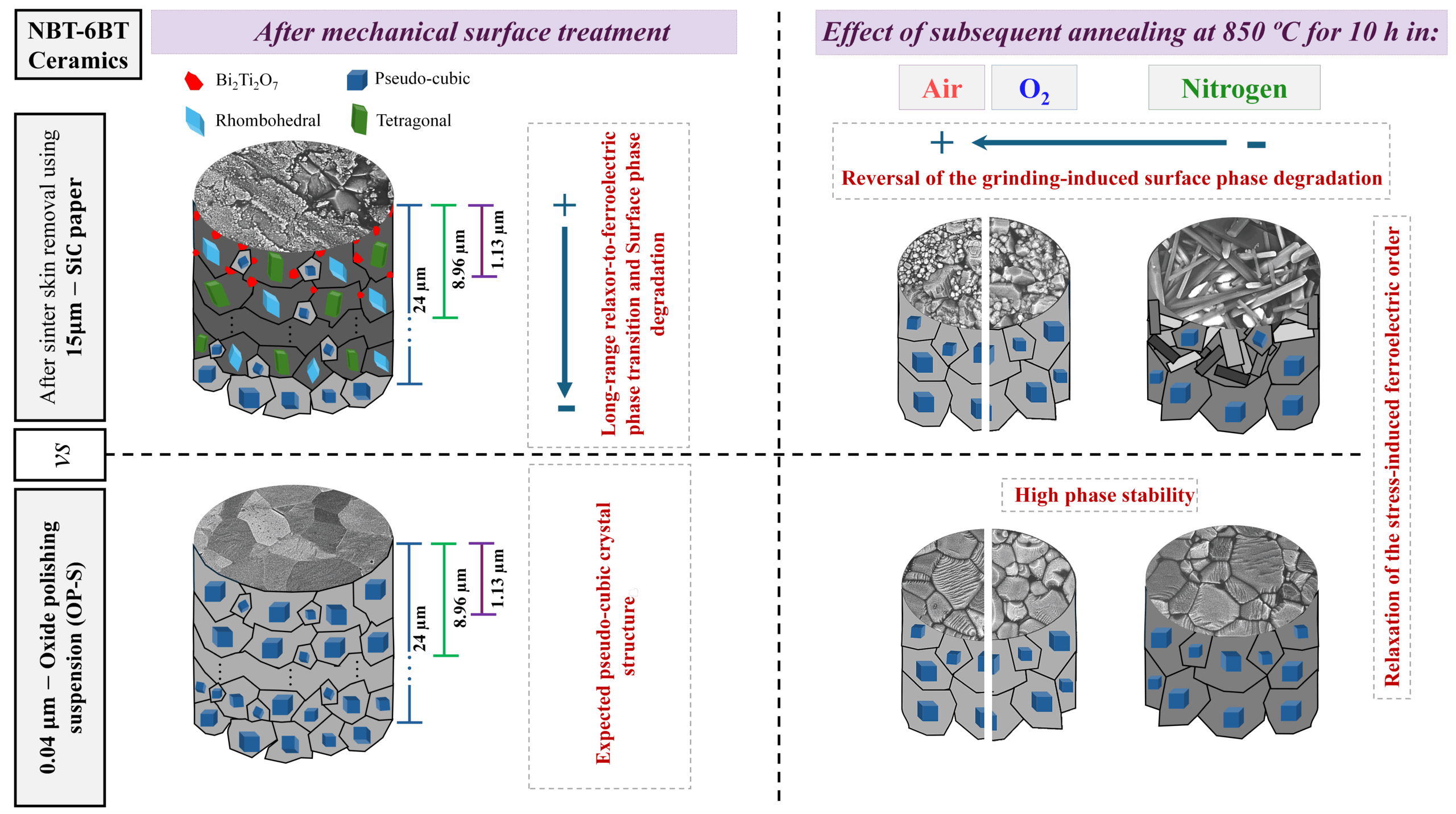

Other researchers have previously tried to mix plastic with cement, although the combination decreased concrete’s strength. In this case, the MIT students discovered that shooting gamma rays at the plastic changed its crystalline structure, making it stiffer and stronger. So they decided to test the irradiated plastic’s strength in concrete.

The students used plastic flakes from a local recycler and exposed them to various levels of gamma rays, ranging from low to high doses. After grinding them into powder, they mixed the irradiated plastic powders with different cement paste samples plus a mineral additive—fly ash or silica fume. They then mixed the powder samples with water, put them into molds, and performed compression tests after the samples hardened into concrete—comparing them to samples made with regular plastic and those that contained no plastic.

Stronger concrete

The team found that samples containing non-irradiated plastic were the weakest. And samples that contained the mineral additives were stronger than cement without plastic. But the irradiated plastic plus the fly ash additive increased concrete’s strength by up to 15%—even more so than just cement mixed with high-dose irradiated plastic, according to the news release.

Further analysis using X-ray diffraction, backscattered electron microscopy, and X-ray microtomography revealed that the high-dose irradiated plastic contained more molecular cross-linking in its crystalline structures, which contributed to the increased density of concrete samples.

“The irradiated plastic has some reactivity, and when it mixes with Portland cement and fly ash, all three together give the magic formula, and you get stronger concrete,” Kunal Kupwade-Patil, research scientist in the Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering and team member, says in the release.

Just by replacing 1.5% of concrete with irradiated plastic can not only improve concrete’s strength, but, when done at scale, also could possibly lower concrete’s carbon footprint.

“Concrete produces about 4.5% of the world’s carbon dioxide emissions,” Short notes. “Take out 1.5% of that, and you’re already talking about 0.0675% of the world’s carbon dioxide emissions. That’s a huge amount of greenhouse gases in one fell swoop.”

Did you find this article interesting? Subscribe to the Ceramic Tech Today newsletter to continue to read more articles about the latest news in the ceramic and glass industry! Visit this link to get started.

Author

Faye Oney

CTT Categories

- Basic Science

- Cement

- Environment

- Manufacturing