Live Science reported that researchers have built a new super-small “nanodragster” that could speed up efforts to craft molecular machines.

“We made a new version of a nanocar that looks like a dragster,” said James Tour, a chemist at Rice University who was involved in the research. “It has smaller front wheels on a shorter axle and bigger back wheels on a longer axle.”

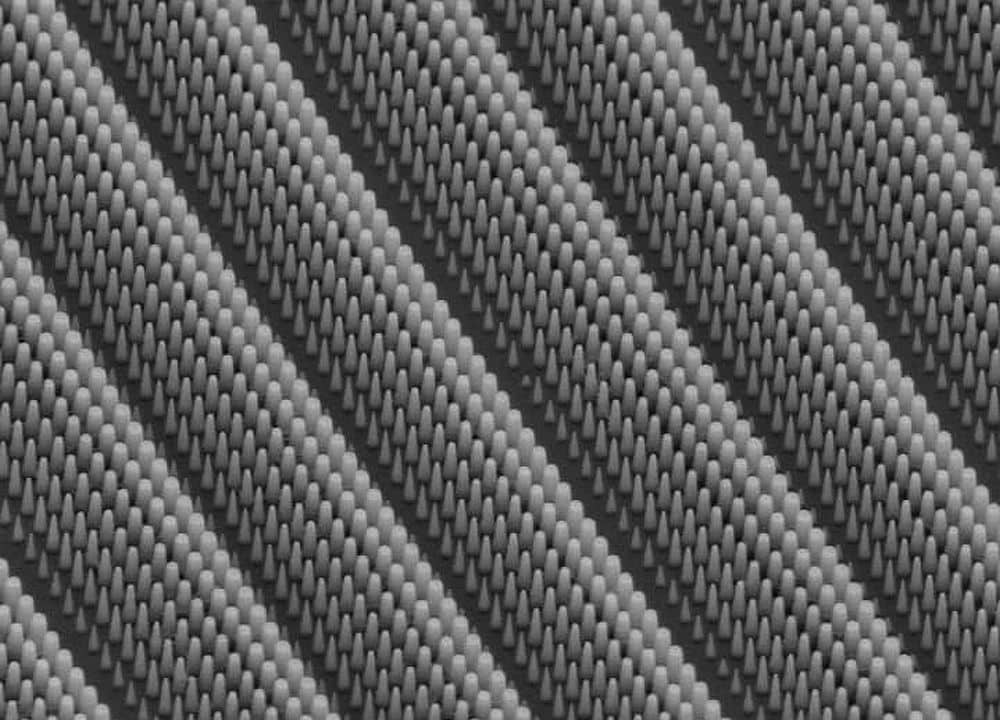

The vehicle is about 50,000 times thinner than a human hair and is pushed along by heat or an electric field.

Spherical molecules called buckyballs made of 60 carbon atoms each serve as the big rear wheels. Due to chemical attractions, these wheels nicely grip the “dragstrip,” which is made of a superfine layer of gold rather than pavement. For the front wheels, the scientists opted for a less sticky compound, p-carbonane.

Tour’s group built nanocars before with buckyballs as all four wheels, but these autos hug the road too tightly and require temperatures around 400 F to get rolling. Nanocars with all p-carbonane wheels, on the other hand, slip and slide as if on ice, said Tours, making them difficult to image and study.

By incorporating both wheel types, the nanodragster can cruise at lower temperatures with greater agility and range of motion.

To make the new nanodragster, Tour’s team started with a previously built, off-the-shelf short axle and front wheel unit in their lab, which is sort of a nano-Monster Garage. They then chemically hooked this up to a pair of aligned hydrocarbon molecules called phenylene-ethynylene-the vehicle’s chassis. The rear axle came next and finally the buckyball wheels went on.

Once the new nanocar gets rolling, it can reach speeds of up to nine nanomiles, or 0.014 millimeters (.0005 inches), per hour, which is relatively fast for their size, said Tour.

The tiny hot rods can also do tricks. “Because the front wheels don’t stick to the surface as strongly, they’re more prone to lift up, so [the nanodragster] does seem to pop a wheelie at times,” Tour told Top Ten Reviews.

By learning how to drive nanovehicles, Tour hopes to pave the way for small but technologically useful structures, such as electronics, that could be built atom-by-atom.

The research appeared in a recent issue of the journal Organic Letters.

CTT Categories

- Electronics

- Material Innovations

- Nanomaterials

- Transportation

Related Posts

Sports-quality ice: From pond side to precision Olympic engineering

February 12, 2026