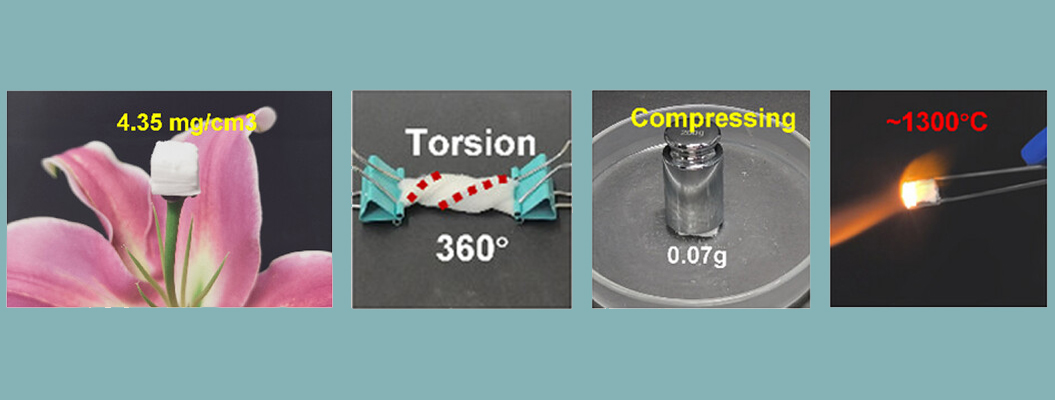

A 5 nm silicon nanowire can be repeatedly broken and reconnected by applying a pulse of varying voltage through the silicon oxide, creating a two-terminal resistive switch. A chip with 1,000 of these silicon-oxide/silicon nanowire memory elements has been assembled as a proof-of-concept.

It’s not often that “plain vanilla” silicon oxide makes the front page of a paper like the New York Times, but it happened when Rice University scientists announced that they have created the first two-terminal memory chips based on silicon oxide in a way that they say should be easily adaptable to nanoelectronic manufacturing techniques, and promises to extend the limits of miniaturization subject to Moore’s Law.

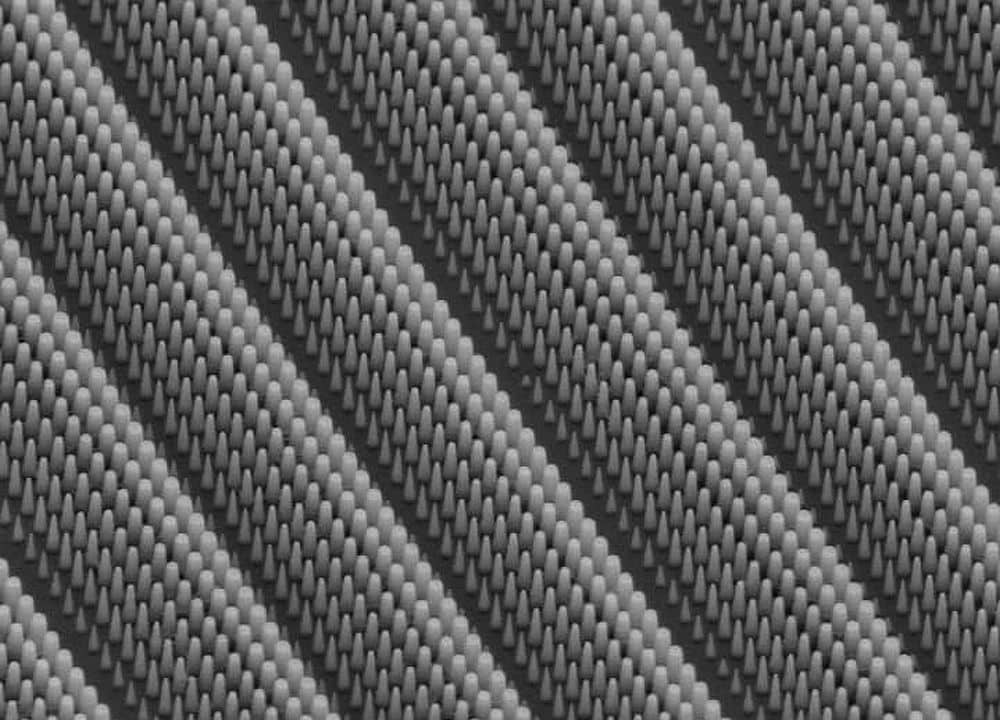

Their technique creates nanocrystal wires that are as small as 5 nanometers wide, far smaller than circuitry in even the most advanced computers and electronic devices. The Rice group believes its nanocrystal conductors could lead to massive, robust 3-D storage.

“The beauty of it is its simplicity,” says James Tour, Rice’s T.T. and W.F. Chao chair in chemistry as well as a professor of mechanical engineering and materials science and of computer science. That, he said, will be key to the technology’s scalability. Silicon-oxide switches or memory locations require only two terminals, not three (as in flash memory), because the physical process doesn’t require the device to hold a charge.

According to the Rice press release:

“[Graduate student] Jun Yao sandwiched a layer of silicon oxide, an insulator, between semiconducting sheets of polycrystalline silicon that served as the top and bottom electrodes.

“Applying a charge to the electrodes created a conductive pathway by stripping oxygen atoms from the silicon oxide and forming a chain of nano-sized silicon crystals. Once formed, the chain can be repeatedly broken and reconnected by applying a pulse of varying voltage.”

Layers of silicon-oxide memory can be stacked in three-dimensional arrays. “I’ve been told by industry that if you’re not in the 3-D memory business in four years, you’re not going to be in the memory business. This is perfectly suited for that,” Tour says.

Silicon-oxide memories are compatible with conventional transistor manufacturing technology, says Tour, who recently attended a workshop by the National Science Foundation and IBM on breaking the barriers to Moore’s Law, which states the number of devices on a circuit doubles every 18 to 24 months.

Austin tech design company PrivaTran is already bench testing a silicon-oxide chip with 1,000 memory elements built in collaboration with the Tour lab.

The findings were published in Nano Letters.

CTT Categories

- Electronics

- Material Innovations

- Nanomaterials

Related Posts

Sports-quality ice: From pond side to precision Olympic engineering

February 12, 2026