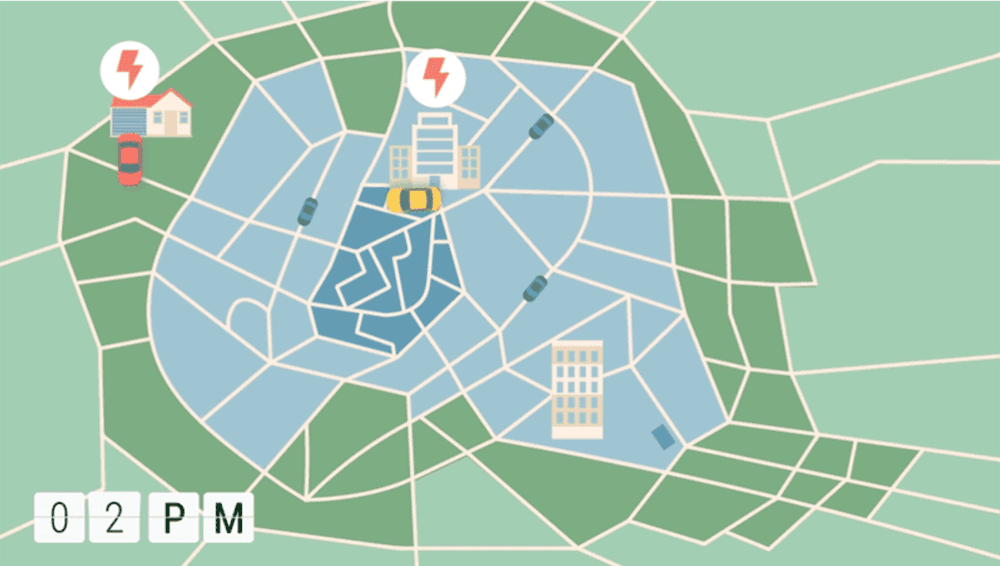

[Image above] Expanded charging infrastructure and access to supplementary long-range vehicles are two important parts of developing a strong electric vehicle ecosystem. Credit: Trancik Lab, Massachusetts Institute of Technology

Ever since Joe Biden took office, he has signed a dizzying array of executive orders and memorandums, with more being signed every day in accordance with the executive branch’s ambitious schedule.

Of all these presidential actions, the “Made in America” executive order signed January 25 caught my eye because of a commitment Biden made before signing it—that the United States government would replace its entire fleet of cars, trucks, and SUVs with electric vehicles manufactured in the U.S.

The executive order itself does not mandate this replacement. Rather, its main thrust is to direct agencies to close current loopholes in how domestic content is measured and increase domestic content requirements, initiatives that ideally will spur investment in the nascent electric vehicle market.

According to the General Services Administration, as of 2019, the government fleet has more than 645,000 vehicles on the road, of which just 3,200 are fully electric and 1,260 are gas hybrids. Replacing the more than 640,000 gas-powered vehicles would be an enormous undertaking, especially considering that very few automakers are making electric vehicles in the U.S., and none of them currently comply with the “Buy American” and unionized labor provisions.

Even if U.S. automakers were prepared to manufacture that many electric vehicles, the U.S. sorely lacks the infrastructure necessary to support an electric vehicle ecosystem. Fortunately, numerous research groups are investigating solutions for improving the infrastructure, such as one group at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT).

The MIT researchers are led by associate professor of energy studies Jessika Trancik. They recently published a study that focuses on two potential solutions to support electrification: expanded charging infrastructure, and access to supplementary long-range vehicles (e.g., private or commercial car sharing, or an additional car at home).

“Expanded home, work and public charging infrastructure may address both real and imagined range constraints by allowing drivers to charge between and during trips,” they write in the paper. “Accessing a supplementary vehicle with a longer range than the personally owned BEV [battery electric vehicle] could also address vehicle-days with high energy requirements and thus support BEV adoption.”

Using driving habits in Seattle as the basis for their analysis, the researchers found that the number of homes that could meet their driving needs with a lower-cost electric vehicle increased from 10% to 40% when either highway fast-charging stations were added or availability of supplementary long-range vehicles was increased for up to four days a year.

This number rose to more than 90% of households when fast-charging stations, workplace charging, overnight public charging, and up to 10 days of access to supplementary vehicles were all available. Across all scenarios, charging options at residential locations (on or off-street) was key.

Animation of a city with expanded charging infrastructure to allow most households to meet their driving needs with a lower-cost electric vehicle. Credit: Trancik Lab, Massachusetts Institute of Technology

In the MIT press release, Trancik says there are various ways to incentivize expansion of such infrastructures. “There’s a role for policymakers at the federal level, for example, for incentives to encourage private sector competition in this space, and demonstration sites for testing out, through public-private partnerships, the rapid expansion of the charging infrastructure,” she says. State and local governments can also play an important part in driving innovation by businesses, she adds.

As policymakers make these decisions, though, Trancik says this study should help provide some guidance on where to focus building first. “If you have limited funds, which you typically always do, then it’s just really important to prioritize,” she says.

The paper, published in Nature Energy, is “Personal vehicle electrification and charging solutions for high-energy days” (DOI: 10.1038/s41560-020-00752-y).

Author

Lisa McDonald

CTT Categories

- Environment

- Transportation