Two things out of the box: First, remember, permissum lector caveo (translation: What the hell does Peter know, anyway?). Second, the opinions expressed below are totally my own and should be blamed on no one else.

Thus forewarned … Nature has what strikes me as a very disturbing article out regarding the interesting ways funds from the American Recovery Reinvestment Act—you know, the ones earmarked to provide a sharp stimulus to direct and indirect hiring and spending in the science–technology sector—are being used for obviously non-stimulus purposes.

The story, “Stimulus-Response,” carries this summary one-liner: “The United States’ 2009 financial stimulus bill has provided research with breathing space, rather than the sharp shot in the arm that many anticipated.”

(FYI, just so readers know where I am coming from, my personal point of view is that these types of stimulus programs can be excellent tools to quickly strengthen aggregate demand in the economy, especially during periods when borrowing rates are nearly zero, as long as the funding 1) is substantial in total size; 2) gets into the private economy; and 3) gets into economy quickly.)

Story author Colin Macilwain, seems like he is playing it overly safe or is unable to be able to make up his mind about what’s going on. On one hand, he correctly acknowledges that “the stimulus package as a whole was designed to create jobs and ease the pain of the recession, and at first the administration pledged to get this money distributed and spent as quickly as possible.” [emphasis added]

But from there onwards, the piece is a series of vignettes – focused on ARRA monies available at NIH, NSF and DOE’s Office of Science (collectively $15.1 billion) – about how interesting it is that researchers and institutions have unexpectedly used much of the money to buy “breathing space” for what already exists. For example, there’s this,

From the beginning, however, the funding pulse didn’t have quite the anticipated effects. Duke University in Durham, N.C., for example, expected a hiring rush after it attracted $210 million in ARRA funds, making it one of the ten most successful universities in the country in this regard, says Jim Siedow, Duke’s vice-provost for research. But staffing barely budged. “We gave a party that nobody came to,” he says. “A lot of people used the money to keep the people they already had.”

In the next paragraph, Macilwain reports

[D]espite the early political pressure to get the money out of the door quickly, agencies have allowed funds to be released gradually, to avoid waste.

Macilwain does suggest that whatever claims of job creation reported under ARRA funding are suspect because they rely on self-reported data and may reflect the continuation of previously existing jobs.

Finally, a chart accompanying the story says that NIH, NSF and the Office of Science have only spent 55 percent of their ARRA allocations. (In fact, DOE, alone, has left unspent $15 billion of ARRA money.)

Macilwain is overly generous when he describes what’s going on as a “stretching out and morphing.” He and Nature may not want to say it, but this pretty clearly indicates some enormous failures in the ARRA.

Let me be clear here: The criticism isn’t that the monies won’t eventually be helpful to R&D — they will be. My criticism is that the monies, now, can’t be helpful in the ways that would have been the most helpful and with the greatest impact for science and the nation.

The most glaring failure is that the administration and these agencies have not spent the ARRA money fast enough. As I have written before, I think that DOE Secretary Steven Chu was exactly right when in February 2009, just two days after the ARRA legislation was signed, he announced “a sweeping reorganization of the DOE’s dispersal of direct loans, loan guarantees and funding contained in the new recovery legislation. The goal of the restructuring is to expedite disbursement of money to begin investments in a new energy economy that will put Americans back to work and create millions of new jobs.” Chu also went on to promise to disperse 70 percent of the investment by the end of 2010.

But, the DOE didn’t come close to that dispersement goal in 2010 and it looks like it won’t make it by the end of 2011 either. As the chart above indicates, the agency reports this week that it has only spent 56 percent of its ARRA funds. With unemployment around 10 percent, leaving $15 billion on the table is an administrative shame and embarrassment.

A couple of important distinctions and economic points must be made here in regard to the concept of “spending” in this context. ARRA money that is held by a principle investigator or an institution but unspent is far different than DOE, NSF or NIH unspent monies. Dispersed money is in the economy and is arguably stimulating, well, something. Undispersed money is not in the economy and stimulates nothing because it is “funny money” that doesn’t really exist until the checks are sent and cashed. It’s not like DOE has the undispersed $15 billion in a bank account somewhere.

Put even another way, by definition, as soon as either funder or fundee starts to play the game of “stretching out and morphing” nondispersed stimulus funds, the funds cease to be able to stimulate anything.

In its defense, the DOE would probably point to the approximate 45,000 jobs it claims to have created via the ARRA, but as noted above, that number would hold more weight if it was verified and actually represented all new jobs.

What went wrong? My guess is a couple of factors have created failures at the policy level. The first factor is that it appears that the agencies have been overly preoccupied with accountability. Regardless of the Solyndra situation (which still looks to me to be about malfeasance and not accountability), DOE and the others should have figured out a way to issue all ARRA funding shortly after it was allocated. (All of the DOE funding has been allocated for over a year.) Unemployment has been and still is a much bigger problem in theory and in fact than the possible misuse of ARRA money.

The second factor is that long-standing agency habits are really, really hard to break. I spent much of two decades trying to change and redesign/reengineer government operations. Getting a large bureaucracy to implement something like a large novel stimulus funding effort is very difficult, but it can be done.

Along these lines, one mystery is what happened to Matt Rogers? Chu selected Rogers, who had been working on energy issues at the well known McKinsey & Co. consultancy, to be the DOE ramrod for whatever changes were needed in the agency to expedite the grants, loans and loan guarantees, and he was given the title Senior Advisor to the Secretary of Energy for Recovery Act Implementation.

Rogers, however, was never very visible to those of us on the outside. On occasion, he would be tasked with making some public appearances. But, while other federal agencies were quick to spend their ARRA money, as I have reported on many times, DOE was slow to spend from the start.

I suspect that Rogers was the right man for in the wrong job. I don’t doubt he had expertise in energy market strategic planning, but I don’t think he had any systems management expertise or track record in this field. It didn’t help that Rogers engaged in the allocation-versus-spending word games or criticism of us writers who nagged about the DOE’s sluggish dispersements. Cocky, premature and inaccurate videos about job creation were also a mistake.

Rogers claimed in September 2010 that DOE jobs would peak during that quarter at 45,000 and hold that level for the next six quarters. In fact, as is apparent in the above graph, (self-reported) jobs numbers didn’t reach or surpass 45,000 until the first quarter of 2011 and appear to be heading downwards already. I, for one, am not surprised that Rogers has quietly returned to his post at McKinsey & Co.

For researchers, keeping a steady flow of funds is never easy. Likewise postdocs and post-postdocs are looking for new opportunities, and lab suppliers are struggling to crawl out of the recession. So, I get that people have to resort to “stretching and morphing” when times are particularly tough. But there is still more than $15 billion unspent. Let’s focus on acknowledging and fixing the ARRA funding bottle necks instead of making up terms that paper-over how dysfunctional things are.

CTT Categories

- Energy

- Market Insights

Related Posts

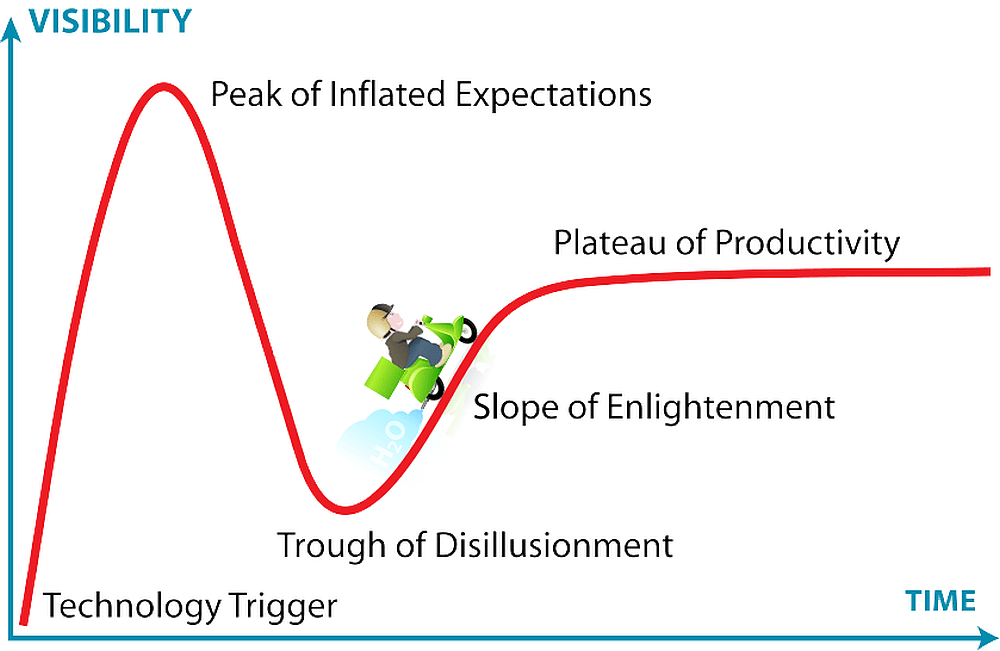

Hype cycles: The uphill climb for hydrogen bikes

June 26, 2025