[Image above] Credit: Richard Rydge; Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

In just a few more weeks, I’m packing my bags, putting up an out-of-office message, and forgetting about my to-do lists—weeklong beach vacation, here I come.

I’m already dreaming of the relaxation that awaits me on Florida’s gulf coast. Ahhh, the sand, the surf, the quiet. There’s just one thing at the beach that I’m not so fond about (too-close-for-comfort shark sightings aside)—the sun.

I’ve espoused my distaste for that burning ball of gas before.

It’s not that I don’t appreciate all that it does to make our planet habitable—it’s just that it wreaks havoc on my mutantly fair skin.

As a redhead at the beach, I slather on copious amounts of SPF 50+ sunscreen, religiously reapplying every couple of hours. And still, I’m only comfortable if I spend my time huddled under huge hats and expansive umbrellas, evading the rays. Because otherwise, I’ll pay the blistering price for a little fun in the intense sun.

Skin cells have a clever natural adaptation to protect themselves from the sun’s UV radiation. That’s why, if you’re lucky, your skin develops the sun-kissed glow of a golden brown tan after a little sun exposure.

So although our society seems obsessed with the aesthetic ideal of bronze skin, a tan is actually a cellular adaptation to protect cells’ DNA from UV damage.

Upon exposure to UV radiation, skin cells produce pigmented melanin particles that travel to the surface of your skin, where they form a miniature intracellular umbrella over your nuclei, protecting DNA from radiation-induced damage. The migration of those melanin particles is what causes the physical appearance of a tan.

However, some of us aren’t so lucky. Some individuals have melanin-defective disorders, including albinism and vitiligo, and so don’t produce active melanin, putting them at increased risk of skin cancer.

And then there’s mutants like me, who produce a different form of melanin that doesn’t adequately protect our skin from the sun (redheads and some fair-skinned individuals produce more of a form of melanin called pheomelanin, which provides inadequate UV protection, while dark-haired individuals produce a more sun-protective form called eumelanin).

So because my skin cells aren’t adequately protected from the sun by my cells’ pigment particles, each time I let the sun hit my skin, it’s likely mutating a bit of my DNA—and some of those unlucky mutations can cause skin cancer. And that process is even more accelerated for individuals with melanin-defective disorders.

Considering that each year there are more new skin cancer cases than breast, prostate, lung, and colon cancer incidences combined, skin cancer is a sizeable public health concern.

Some new research, however, has me dreaming of future beach vacations where my mutant skin cells can get a little help from nanotechnology to protect themselves from the sun.

Researchers at the University of California, San Diego have created synthetic nanoparticles that mimic the action of natural melanin. If proven safe and effective, the nanoparticles could someday be developed into a therapy for certain disorders and potentially even a natural sunscreen.

The concept is simple—boost cells’ natural defenses by adding melanin to melanin-defective cells or those that don’t produce adequate amounts of protection. The researchers sought a synthetic route to generate melanin particles because, although many animals produce different forms of melanin, the natural particles aren’t easy to isolate.

By simply oxidizing dopamine, however, the researchers showed that they can manufacture in the lab synthetic melanin nanoparticles that do a pretty good job of mimicking the real stuff, according to a UC San Diego press release.

Scanning electron micrograph of the synthetic melanin-like nanoparticles. Credit: Yuran Huang and Ying Jones; UC San Diego

The researchers’ in-depth characterization of the synthetic nanoparticles indicates that they are good analogues for natural melanin.

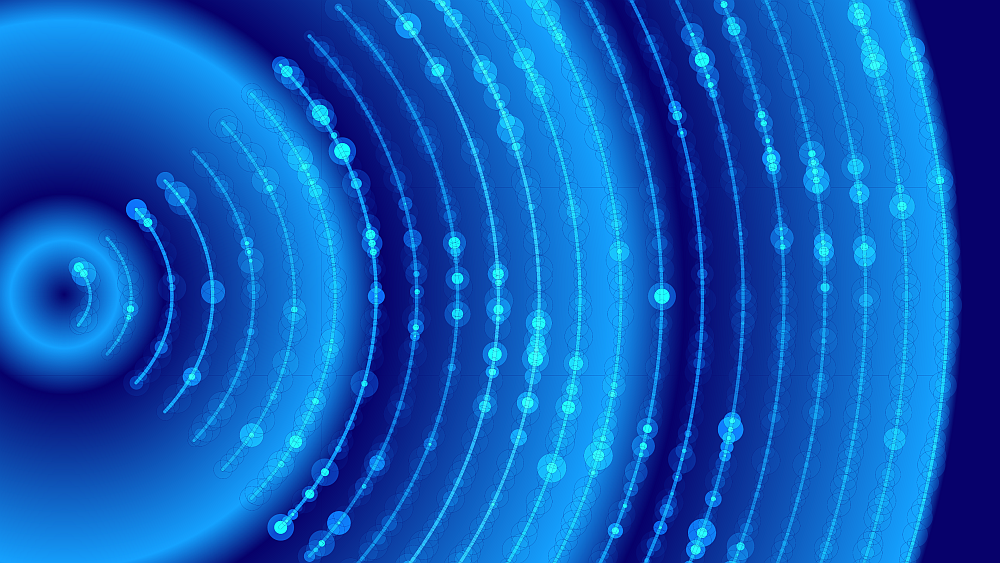

In addition, in vitro experiments show that the synthetic nanoparticles mimic the functional action of natural melanin in cell cultures. Keratinocytes, cells that reside near the skin’s surface, efficiently took up the synthetic nanoparticles, which huddled around the cells’ nuclei to form miniature umbrellas that blocked UV damage in these cells—just like natural melanin.

Synthetic nanoparticles were taken up in vitro by keratinocytes, the predominant cell type found in the outer layer of skin. Credit: Yuran Huang and Ying Jones; UC San Diego

While there remains a lot of work ahead to show that the nanoparticles are safe and effective as a clinical therapy—in addition to developing the most effective way to get the nanoparticles into skin cells—this research has me dreaming.

Rather than relying upon a protective external barrier layer for sun protection, what if we can someday protect our cells from the inside?

With an annual cost of treating skin cancer in the United States alone totaling more than $8 billion, that’s an idea worth exploring.

The article, published in ACS Central Science, is “Mimicking melanosomes: Polydopamine nanoparticles as artificial microparasols” (DOI: 10.1021/acscentsci.6b00230).

Author

April Gocha

CTT Categories

- Biomaterials & Medical

- Environment

- Material Innovations

- Nanomaterials