[Image above] Credit: Ozkan Guner, Unsplash

Though some dental restorations can last for well over 10 years in ideal circumstances, there are numerous situations that necessitate the removal of a restoration sooner.

Fortunately, there are various methods for removing dental restorations. Which method is used depends on factors such as the crown and bridge material, the luting cement (material that secures the restoration to a tooth), location of the restoration, and status of the underlying tooth.

Traditionally, the safest and least traumatic way to remove a restoration is by destroying it. Methods that conserve or semi-conserve the restoration often risk harming the underlying tooth. However, continued research on conservative methods helps mitigate the risk of tooth damage and makes such procedures more desirable options.

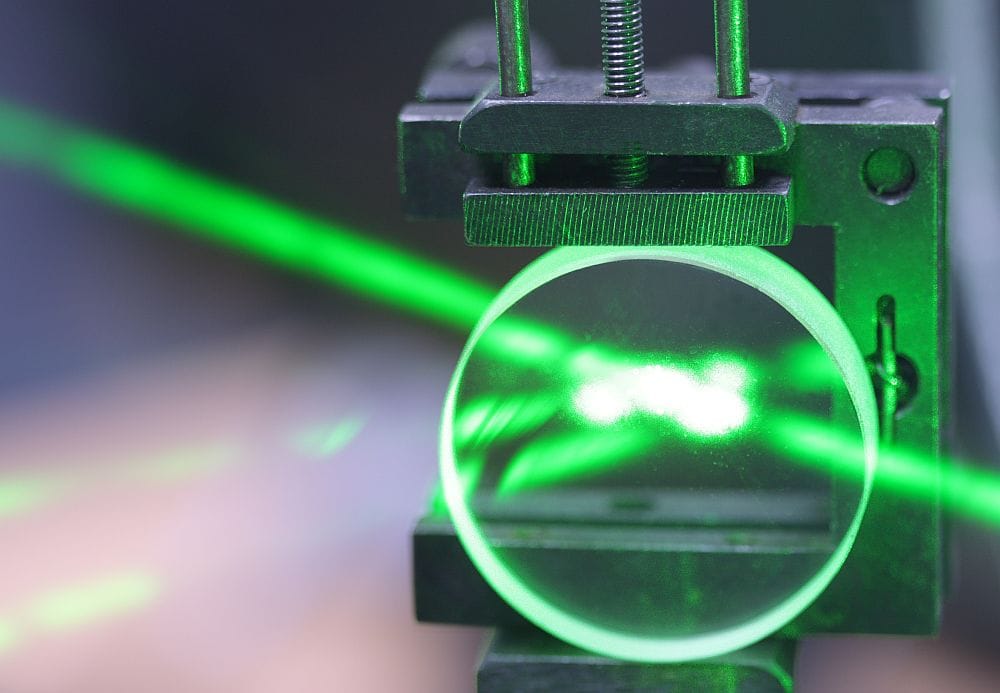

Erbium lasers are a conservative method being explored for removing both ceramic restorations and ceramic appliances (e.g., braces). These lasers emit light in wavelengths that can be transmitted through a translucent ceramic and then absorbed by the water molecules and residual monomers in the luting cement. This absorption results in vaporization of the molecules and debonding of the cement.

The main concern with using erbium lasers to remove dental ceramics is the possibility of thermal injury to the adjacent tissues. An increase in pulpal temperature by 5.5°C can cause irreversible damage to the pulp tissue, while an increase in osseous temperature by 10°C can cause bone damage; increasing temperatures by 6°C can damage periodontal ligaments.

In a recent open-access paper, researchers from Virginia Commonwealth University and Wroclaw Medical University (Poland) reviewed the current literature on erbium laser-assisted ceramic debonding to identify the parameters needed for safe application of this method.

They conducted a comprehensive search of seven databases and identified 4,117 articles published from 2011 to 2021 containing key words. A manual review of the titles and abstracts narrowed the selection down to 53 articles, and a full-text review determined 38 articles for final inclusion in the study.

Among the 38 articles, 15 reported on experiments conducted with orthodontic brackets (braces), nine reported on veneer removal, five studies reported research findings using ceramic disks, six reported on all-ceramic crown removal from natural teeth, and three studied the removal of crowns from various implant abutments.

Notably, all 38 articles involved ex vivo or simulated experiments. As such, the findings “may not be reflective of clinical situations where the patient’s oral structures, tongue and cheek, as well as optimal access to the laser intraorally, can present challenges in manipulating the laser handpiece and application,” the researchers acknowledge.

Some findings from the review are given below.

Material effects on debonding time

Based on the data in these studies, type of luting cement played an important role in debonding time. For example, one highlighted study showed that lithium disilicate crowns debonded from titanium implant abutments in only 97.5 seconds when secured with a resin-modified glass-ionomer cement, while crowns secured with a resin cement required 196.5 seconds.

On the other hand, translucency of a given ceramic appeared to have little influence on debonding. For example, “No significant difference in debonding veneers from bovine incisors was reported among feldspathic ceramics with different translucency,” the researchers write.

However, the type of ceramic did influence debonding time. For example, studies here and here reported that it takes longer to debond a zirconia crown (226–312 seconds) compared to a lithium disilicate crown (190 seconds) from a human molar.

Laser effects on debonding time

Five studies compared the efficiency of debonding between erbium,chromium-doped yttrium scandium gallium garnet (Er,Cr:YSGG) and erbium-doped yttrium aluminum garnet (Er:YAG) lasers. Though time for removal was not always statistically different, debonding times generally were shorter for the Er:YAG laser than the Er,Cr:YSGG laser.

Power and duration of the laser depended on the type of restoration or appliance being removed. For example, one study found removal of an orthodontic bracket required a power of 3 watts, 10 seconds in the scanning mode with energy density 22–28 J/cm2, and pulse duration of 100 μs. In contrast, another study found crown removal required laser settings to be in the range of at least 3.5–4 watts of power with 25 Hz pulse rate.

Laser effects on surrounding tissue and irradiated ceramics

Though thermal injury to adjacent tissues is the main concern when using laser-assisted ceramic debonding, no study reported a significant increase in pulpal temperature beyond the physiological limit of 5.5°C during irradiation with any erbium laser. Pulpal temperature changes typically ranged between 0.71°C to 4.28°C.

Additionally, most studies reported successful removal of restorations or appliances with no detectable physical damage to the irradiated ceramic. Scanning electron microscopy was the most common method used to examine the debonded ceramics, with energy dispersive spectroscopy, secondary electron imaging, or backscattered electrons sometimes applied as well.

Ultimately, “Results from all studies showed that erbium lasers are effective in debonding all ceramic restorations with no damage to abutment teeth/implant and with none or minimal alterations to the ceramic restorative/orthodontic appliance surfaces,” the researchers conclude.

Future directions for research

The researchers write that there is a real need for clinical studies so the in-vivo-based debonding time can be assessed, as well as a patient’s compliance and acceptance of the laser-assisted ceramic debonding.

Additionally, though this review found similar applications of laser settings across studies, researchers need to develop a consensus for this procedure for both Er:YAG and Er,Cr:YSGG lasers.

The open-access paper, published in Journal of Prosthodontics, is “Erbium laser-assisted ceramic debonding: a scoping review” (DOI: 10.1111/jopr.13613).

Author

Lisa McDonald

CTT Categories

- Education