[Image above] Australia-based surfboard company Draft Surf partnered with Spain-based Acconia Energía to create surfboards made from retired wind turbine blades. Credit: Draft Surf, YouTube

Fiberglass takes on many different forms in our everyday lives, through sports equipment, vehicles, housing insulation, and more. Its durable, water-resistant, and lightweight nature is why fiberglass proves to be a popular, versatile material for numerous applications, even though many may not realize it.

For all its benefits, fiberglass unfortunately is not biodegradable, and its composite nature of glass fibers and a binding resin make recycling difficult. These characteristics pose a challenge for disposing of large fiberglass products that have reached the end of their life, such as wind turbine blades.

As of late 2024, there are more than 70,000 active wind turbines in the U.S., and since 1992, 11,000 wind turbines have been decommissioned. With the number and size of wind turbines growing each year—and the maximum lifespan being only 30 years—the National Renewable Energy Laboratory estimates that more than 2 million tons of wind turbine blades in the U.S. will need to be retired by 2050. The question arises: Where do the blades go next?

Progress in recycling glass fibers from wind turbine blades

Currently, most wind turbine blades are stored in landfills at the end of their life because there are few widely available, cost-effective recycling options on the market. However, in recent years, several companies have made strides in extracting and reusing glass fiber from wind turbine blades, typically using pyrolysis-based processes.

Pyrolysis involves heating up the decommissioned blades at high temperatures in an oxygen-free environment. The absence of oxygen allows the materials in the blades to be broken down and separated.

Carbon Rivers in Knoxville, Tenn., developed a glass-to-glass reclamation process that allows them to recover clean and mechanically intact glass fibers from end-of-life turbine blades. As explained in the January/February 2024 Bulletin cover story, the company is collaborating with automotive manufacturers to supply them with the fibers recovered from this process.

Similarly, the Danish consortium behind the DecomBlades innovation project used pyrolysis to recover and remelt glass fibers for use in new wind turbine blades. Meanwhile, researchers at Kaunas University of Technology in Lithuania took the pyrolysis process a step further by introducing a catalyst, which lowered the reaction activation energy and thereby reduce the required pyrolysis temperature.

Besides recovering the glass fibers, some companies have explored the development of recoverable binding resins as well, which would enable fully recyclable wind turbine blades. For example, in 2022, the ZEBRA (Zero wastE Blade ReseArch) consortium created the first 100% recyclable wind turbine blade made using Arkema’s Elium resin. The blade was deployed by LM Wind Power, a subsidiary of General Electric.

Though many blade recycling processes are still in development and have yet to be made widely available, these efforts help improve the overall sustainability of wind turbine blades.

Options for repurposing wind turbine blades after decommissioning

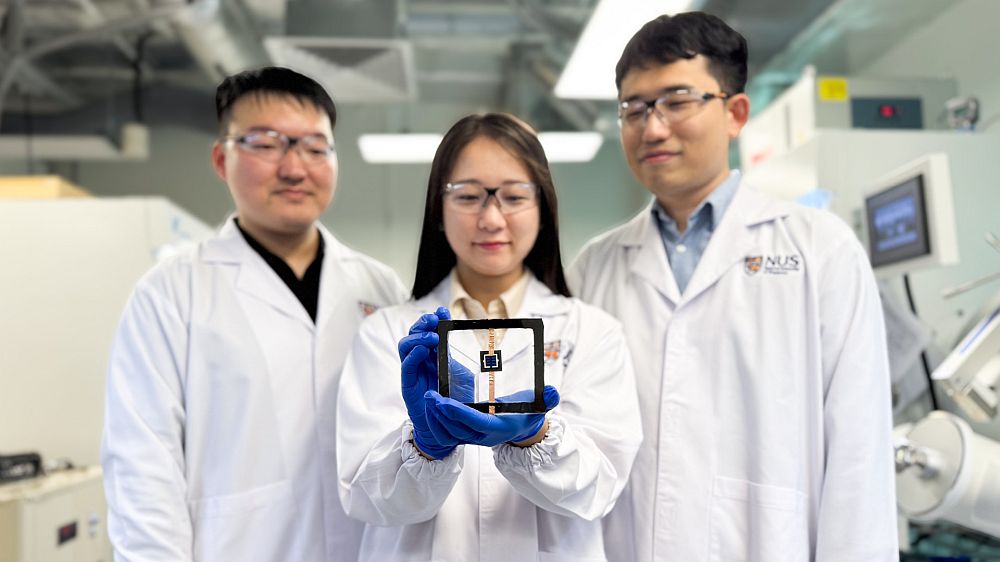

While recycling the materials from wind turbine blades has its advantages, some companies have devised ways to reuse the blades exactly as they are. For example, Australian company Draft Surf started using decommissioned wind turbine blades to create surfboards, in which part of the deck or body of the board is constructed from the old blade or used in the fins for stability and speed.

Draft Surf partnered with Spain-based renewable energy company Acciona Energía on this product. Acciona supplies the decommissioned blades from its Waubra windfarm in Australia as part of its larger Turbine Made initiative, which aims to find alternative ways to repurpose retired wind turbine blades.

Over in Ireland, the Re-Wind Network reuses decommissioned wind turbine blades in various civil engineering projects, such as pedestrian footbridges and bike shelters marketed under the name BladeBridge.

The Re-Wind Network is a collaboration between Queen’s University Belfast in Northern Ireland, University College Cork in the Irish Republic, and Georgia Institute of Technology and City University of New York in the United States. BladeBridge formed as a start-up in 2017 by Re-Wind Network researchers.

Example of the pedestrian footbridges created out of retired wind turbine blades. Credit: BladeBridge

In January 2022, a 5.5-meter-long BladeBridge was installed in Cork, Ireland, with wind turbine blades serving as a guard rail on either side of a steel deck. A second BladeBridge 5.8 meters in length was also installed in Draperstown in Northern Ireland, funded by the Science Foundation Ireland, the Northern Ireland Department of the Economy, and the U.S. National Science Foundation.

BladeBridge also recently debuted a variety of other blade-made products, such as street furniture, picnic tables, bike shelters, community planters, and electric bike charging stations. The charging stations are made from 13-meter blades and can fit up to four bikes.

Continuing the theme of outdoor uses, Netherlands-based architecture company Superuse Studios used retired wind turbine blades to create playground equipment for children. This usage helps offset carbon footprints from the production of traditional playground equipment while still providing a durable, waterproof playground material.

Superuse Studios came up with the concept of the recycled blade playground in 2008, using five decommissioned blades to create a simple, abstract playground design near a small beach in the municipality of Terneuzen. The blades were supplemented with other materials such as ropes, nets, steel slides, and ladders to encourage different types of play among children.

These unique, alternative uses for retired wind turbine blades in urban settings can help keep the material in use for longer periods of time, especially while industrial recycling methods work to become more widely available. Although these unique uses will not keep the blades out of landfills indefinitely, they represent sustainable, forward thinking that can help propel the renewable energy sector toward an even greener future.

Author

Helen Widman

CTT Categories

- Energy

- Market Insights