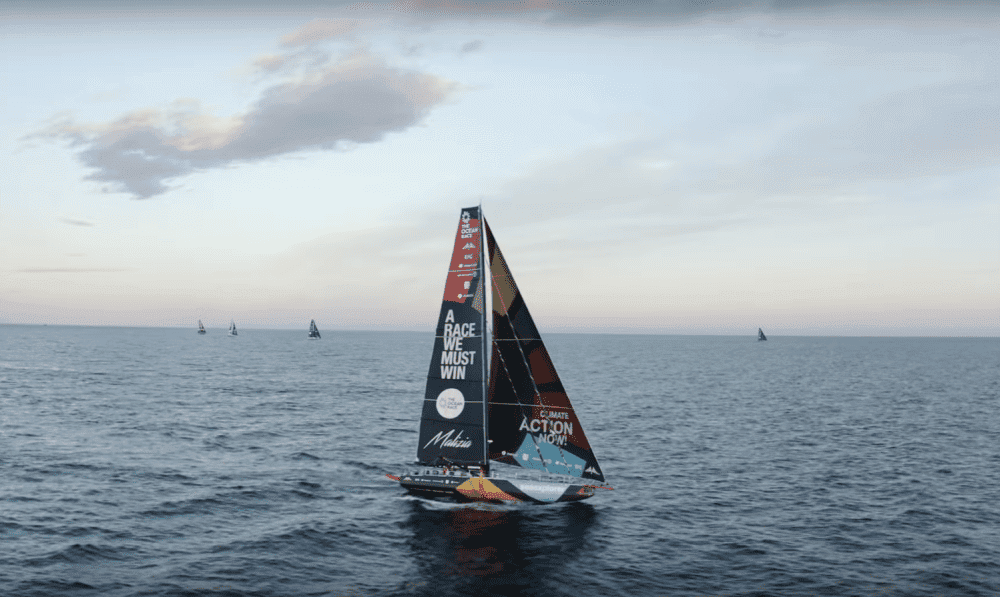

[Image above] A view of some of the boats competing in this year’s Ocean Race. The sailors on each ship will gather scientific data during the race to provide insights on weather, climate change, and microplastics in the ocean. Credit: The Ocean Race, YouTube

This decade is the United Nations Decade of Ocean Science for Sustainable Development. The goal of this Decade is to provide a common framework for designing and delivering solution-oriented research needed for a well-functioning ocean in support of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development.

Diverse stakeholders have a role to play in accomplishing this goal. However, you may be surprised to learn that one group actively contributing to the mission are organizers and participants in the Ocean Race, an international boat race that sees competitors sail around the entire world in about six months.

The Ocean Race: A brief history

The Ocean Race is often described as the longest and toughest professional sporting event in the world. It is held every three or four years since 1973.

The event originally was named the Whitbread Round the World Race after its initiating sponsor, British brewing company Whitbread. In 2001, it became the Volvo Ocean Race after Swedish automobile manufacturer Volvo took up the sponsorship. Following the end of Volvo’s tenure in 2018, the new owner—a Spanish company called Ocean Race 1973 SLU—renamed it the Ocean Race in 2019.

Early races had a large range of boat types, but ships were restricted to a single design in the 1990s due to concerns about the advantages that the biggest “maxi” boats had over the rest of the field. However, for the 2023 edition of the race, two classes of boats are being used: the Volvo Ocean 65 (current standard) and the IMOCA 60, which both feature a single hull made of carbon fiber.

In an interview, one of the event’s new owners, Johan Salén, explains why they chose to add the IMOCA 60 as an option.

“Adding the IMOCA 60 class to the existing VO65 fleet brings back a design and technology element, which has traditionally been a big part of the race. It adds another layer of complexity to the project, which is interesting for the sailors, designers and engineers, and ultimately for the fans as well,” he says.

The route changes slightly each year to accommodate various ports of call, but recent editions typically have either 9 or 10 legs, with in-port races at many of the stopover cities.

This year, the race will feature only 7 legs, starting in Alicante, Spain, and ending in Genoa, Italy, for a total of 32,000 nautical miles. Leg 3 of the 2023 race from Cape Town, South Africa, to Itajaí, Brazil, sets a record for longest racing distance ever in the event’s history, with 12,750 nautical miles. A tracker on the Ocean Race website shows the current whereabouts of each boat in the 2023 race.

Learn more about Ocean Race history in the video below.

Credit: The Ocean Race, YouTube

The Ocean Race science program: Capturing ocean data in remote areas

An innate feature of the Ocean Race is that competitors traverse regions of the ocean that otherwise are rarely traveled. So, why not take the opportunity to gather valuable scientific data that can help scientists monitor ocean health?

In 2017, the Ocean Race organizers launched a new science program to run in tandem with the race. As competitors raced between the ports, they measured a range of variables to help provide insights on weather, climate change, and microplastics in the ocean.

One way they measured variables was by deploying 30 scientific drifter buoys, which gathered data on sea surface temperature, ocean currents, and the Earth’s climate. They also brought onboard sampling equipment to measure carbon dioxide, sea surface temperature, salinity, and chlorophyll a.

Two teams also measured levels of microplastic pollution and found it to be widespread, even in the most remote locations. Out of a total of 86 water samples taken during the 2017–2018 race, a staggering 93% contained microplastic pollution. The video below features an interview with one of the sailors who helped measure microplastic pollution.

Credit: The Ocean Race, YouTube

For the 2023 race, the science program is being expanded to equip even more boats with specialized equipment. For example, some boats will feature equipment that can measure trace elements, including iron, copper, manganese, zinc, nickel, cobalt, lead, chromium, and cadmium. This information helps scientists understand why phytoplankton—a key part of ocean and freshwater ecosystems—grows in some areas and not others.

In an Ars Technica article on the 2023 race, Stefan Raimund, science lead for the Ocean Race, says creating scientific instruments that fit onto the racing boats was a challenge.

“On research vessels, you have an instrument the size of a large fridge—typically, you have two of those big boxes on board, and they do more or less automatic measurements,” Raimund says. “The challenge was to make it small enough and lightweight enough to put on race boats, and it needs to be very robust and easy to use, and it must withstand accelerations, shocks, vibrations, or the hazards you find on sailing boats. That meant cutting the equipment package’s weight from about 882 lbs (400 kg) to 42 lbs (19 kg).”

“Power consumption was important, too—not something one normally has to worry about on a research vessel—and importantly, the OceanPack had to work autonomously. The crew of five are all sailors, not scientists,” he adds.

As such, the scientific instruments on the Ocean Race boats feature only three buttons—an on-off button, a standby or operate button, and a copy data button—and one place for inserting a USB key.

“Really everyone can understand the system within 30 minutes,” Raimund says.

The video below provides a closer look at some of the scientific instruments.

Credit: The Ocean Race, YouTube

Sustainability in Ocean Race boat design

In addition to collecting data that helps scientists manage ocean sustainability, the Ocean Race teams aim to make the race itself more sustainable.

In 2021, the IMOCA skippers voted for rules to measure each team’s embrace of sustainable development. These rules include

- Life cycle assessment requirement. Teams must carry out a life cycle assessment throughout the construction of a new boat to better understand the impact and decide on practical ways to reduce their footprint.

- Alternative material usage. The rules favor the use of alternative materials for nonstructural and removable elements of the boat (e.g., chart table, seats, bunks, internal panels), which will be subtracted from the boat’s measurement weight within a 100-kilo limit.

- Teams Charter. The IMOCA Teams Charter brings together seven themes to help teams make a progressive transition to sustainability with concrete and quantified objectives.

- Green sail requirement. Every competitor must carry one “green” sail among the eight permitted in the IMOCA GLOBE SERIES Championship races. This sail can be made from alternative materials and/or be fully recyclable.

- Green energy requirements. An IMOCA boat is expected to sail around the world virtually self-sufficiently in terms of energy thanks to hydrogenerators, solar energy, and wind turbines. A diesel engine is retained for safety reasons, but the rule allows teams with an alternative solution for motorization to initiate a study into it to obtain an exemption.

In the Ars Technica article, the U.S. 11th Hour Racing Team describe how they worked to minimize the carbon impact of building their boat by experimenting with lightweight, sustainable materials, such as balsa or composites made from flax. Further details are provided in their sustainable design and build report.

Author

Lisa McDonald

CTT Categories

- Environment