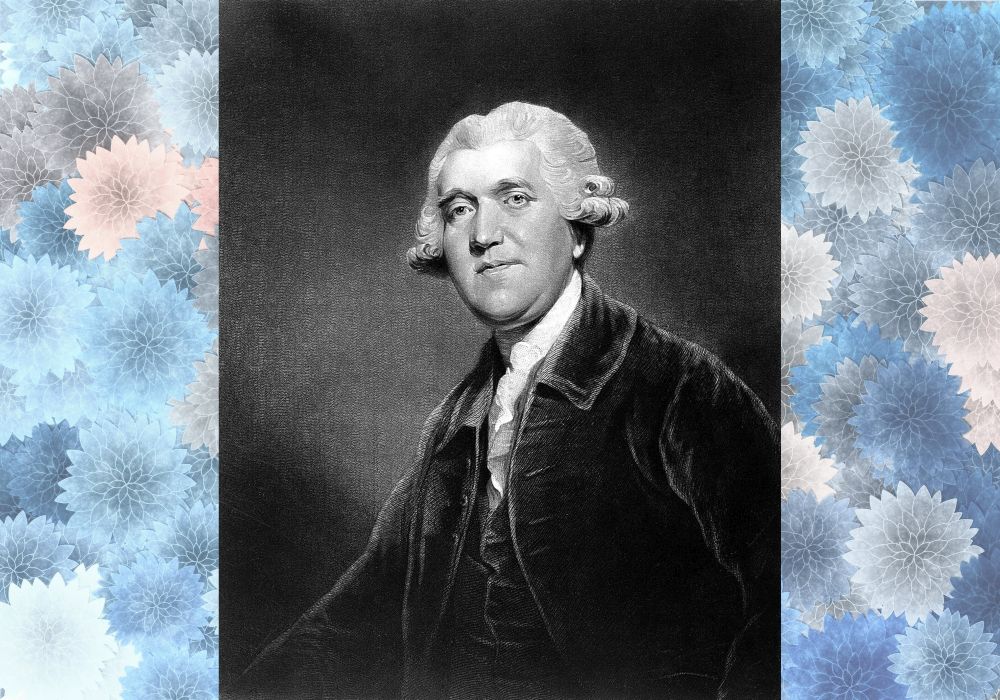

[Image above] Section of a glass-based lenticular mural at the North Carolina Zoo, created by artist Rufus Butler Seder. Photo by Lisa McDonald.

The good and bad thing about materials science is that once you learn the basics of this discipline, you’ll start seeing learning opportunities everywhere you go—even on vacation. That is what happened to me earlier this month during a road trip with my dad through North Carolina, when we visited the North Carolina Zoo.

Known as the world’s largest natural habitat zoo, the North Carolina Zoo encompasses 2,600 wooded acres, 500 acres of which are developed. It is home to more than 1,800 animals, yet the exhibit that stopped me dead in my tracks was one of the zoo’s many art collections, specifically Arctic Turns.

Arctic Turns is a series of nine murals with images that appear to move as the viewer walks by them. What makes these murals so fascinating, however, is that they are made of glass tiles.

Credit: Lisa McDonald

Credit: Lisa McDonald

The murals are an example of lenticular printing, or a method to produce printed images with the ability to change or move as they are viewed from different angles.

This multistep process involves arranging (slicing) an image into strips, which are then interlaced with one or more similarly arranged images (splicing). This printed back layer is then covered with a clear lens that refracts the light so only specific images can be seen from certain angles.

The clear lens used in lenticular printing is typically plastic, commonly polyethylene terephthalate glycol, acrylic, or polystyrene. But in the case of the Arctic Turns murals, ribbed glass is used instead.

Rufus Butler Seder is the artist who developed this glass-based lenticular printing method, which he calls LIFETILES. On his website, he shares a detailed behind-the-scenes look at how he developed the technology.

To make the glass murals more permanent, Seder learned how to sandblast the interlaced images into the backs of each 3-pound, 8-inch square tile. The sandblasted tiles then get painted, scraped, fired in a kiln, and finally added piece by piece to the LIFETILES mural.

Credit: Rufus Seder, YouTube

Besides the North Carolia Zoo, Seder has installed LIFETILES murals in many other public places throughout the United States and around the world, including Taiwan, Kuwait, Greece, and Germany. A full list of public installations can be seen here.

Unsurprisingly, the development of a LIFETILES tile is a painstaking process, and a LIFETILES installation can take up to a year to complete. On his website, Breder says, “I couldn’t do all this without the assistance of a team of extremely talented professional artists and art students recruited from Boston’s higher caliber art schools.”

Author

Lisa McDonald

CTT Categories

- Art & Archaeology

- Glass