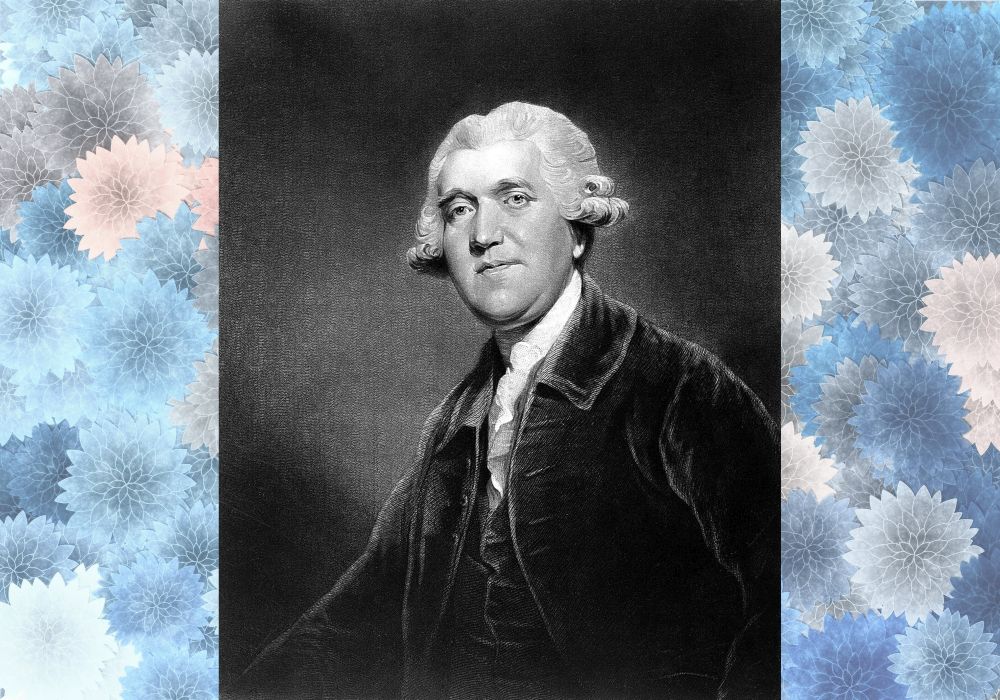

[Image above] Example of Chu Dau vases. Only recently was the rich history of ceramics in Hải Dương Province, Vietnam, uncovered. Credit: Hungda, Wikimedia (CC BY-SA 3.0)

When it comes to the history of ceramics in Asia, many people immediately think of China.

The history of Chinese ceramics traces back over thousands of years. Porcelain in particular holds an important place in the history, as the material was invented in China over centuries and then exported throughout the world. Even today people refer to porcelain as “fine china” in reference to this history.

Of course, China is not the only Asian country with a history of ceramics. However, for some countries like Vietnam, the history of ceramics was lost in time—until recently, that is.

Vietnam’s role in the global ceramic trade of the 15th and 16th centuries came to light in the 1980s following the reexamination of an ancient vase that previously was attributed to a Chinese workman. Today, Chu Dau ceramics (named for a village in Hải Dương Province, Vietnam) are recognized as a unique type of Vietnamese ceramic distinct from the Chinese and Japanese ceramics of the same period.

In September last year, a subdivision of Vietnam Television called VTV World released a three-part documentary looking at this hidden history of Vietnamese ceramics. Below is a summary of that history, including links to each of the three parts.

The story begins: Vase of Annam

The Vase of Annam is a Chu Dau ceramic located in the Topkapi Sarayi Museum in Istanbul, Turkey. It first came to the attention of the art world in 1933, when British civil servant and antiquarian Robert Lockhart Hobson published an article about it in Transactions of the Oriental Ceramic Society 1933–1934.

In the article, Hobson attributed the vase to a Chinese workman named Chuang, based on how he translated the 13 Chinese characters written along the shoulders of the vase. But more than 40 years later, a reexamination of the characters by Southeast Asian art historian Roxanna Brown in 1977 revealed something startling.

Brown realized the characters should be translated as Vietnamese rather than Chinese. (The Vietnamese written language is based on Chinese characters, hence the confusion.) When translated this way, the potter’s name became Bui, and the character “Thi” placed after the name identified the potter as female!

The other characters along the vase’s shoulders indicated the potter Bui Thi Hy lived in the Nam Sách District of Hải Dương Province, Vietnam, and she made the vase in 1450. And with these clues, the search for Bui Thi Hy began.

In 1980, a Japanese diplomat named Makoto Anabuki sent a letter to local authorities of the then Hải Hưng Province in Vietnam to learn more about the mysterious potter. (Hải Hưng has since split into two provinces, Hải Dương and Hưng Yên.)

“What was the person named Bui Thi Hy like?” he asked.

Anabuki would not know it, but his simple question would set off a years-long search for answers and lead to the uncovering of Chu Dau’s rich ceramic history.

Discovering Chu Dau ceramics

Prior to Anabuki’s letter, no one in Hải Dương Province was aware the craft of ceramics had existed in their locality.

“There were antiques in government and private collections, but they were wrongly categorised as ceramics from Bat Trang, 16 km north of Ha Noi,” an article on the history of Chua Dau ceramics explains. “The closest matches local archaeologists could find were inscriptions found on oil lamps by craftsman Dang Huyen Thong in Thanh Lam District, located only two kilometres from Chu Dau.”

After reading the letter, the provincial Museum and archeologist Tang Ba Hoanh decided to investigate the vase’s origins. And since 1980, seven excavations in Hải Dương Province—plus the excavation of a shipwreck off the shores of Hội An city in 1997–1999—revealed ancient ceramic kilns and tens of thousands of artifacts.

Part one of the documentary below goes into more detail of the initial discoveries.

Credit: VTV World, YouTube

Many of the ceramics come from the village of Chu Dau in Hải Dương Province. The Chu Dau ceramics are made from white clay collected in Chí Linh, a city in Hải Dương Province where six rivers intersect. And compared to Chinese and Japanese ceramics made during the same period, Chu Dau ceramics are unique.

“It has its own style of inscription, design, and making-skills. It is truly Vietnamese,” Nguyen Van Cuong, director of the Vietnam National Museum of History, says in part three of the documentary.

Unfortunately, war at the end of the 16th century destroyed Chu Dau, including all big ceramic kilns in Nam Sách District. That is why no one was aware of the area’s history until Anabuki’s letter in 1980.

But the question still remains—who was Bui Thi Hy?

Bui Thi Hy: The search for truth

The question is not just who Bui Thi Hy was—some researchers debate if she existed at all.

The debate arises from how one chooses to read the Chinese characters. As seen below, if the characters “Bui,” “Thi,” and “Hy” are placed together, then the inscription reads as “written by or painted by Bui Thi Hy.” But if the characters “Hy” and “But” are read together instead, then the inscription reads “a Bui artisan drew this for fun.”

(Left) The Vase of Annam inscription; the red characters are the ones in question. (Center) How the characters are read if Bui Thi Hy is the name of the potter. (Right) How the characters are read if translated “a Bui artisan drew this for fun.” Credit: VTV World, YouTube

For people who believe in the former translation, there are other documents they point to as proof of Bui Thi Hy’s existence. For example, the stone lotus pillars located at Vien Quang Pagoda in Gia Loc District, Hải Dương Province feature inscriptions that read “Bui Thi Hy funded for building the pagoda.” (Opponents say because the inscriptions appear to be re-inscribed, they cannot be taken as proof.)

Likely the surest proof, though, comes from genealogical documents kept by the Bui family still living in Nam Sách District. These documents include an ancestor named Bui Thi Hy.

“However, whether she made the blue-and-white vase in Turkey and how that vase was transported from Nam Sách District to Istanbul is a question experts are trying to answer by collecting further evidence,” the third part of the documentary explains.

The second part of the document (below) goes into more detail on what is known about Bui Thi Hy.

Credit: VTV World, YouTube

Though the question of Bui Thi Hy’s existence and role in the ceramic trade remains, experts emphasize she was ultimately the catalyst, not focus, of this story.

“The most important thing is that the Vietnamese blue-and-white vases were introduced to the world, illustrating a prosperous time for Vietnamese ceramics,” says Augustine Ha Ton Vinh, senior investment advisor to Vietnam’s Special Economic Zone and Integrated Resorts, in part three of the documentary.

And those prosperous times may come back. To honor the area’s history, Chu Dau villagers are actively working to revive the ancient craft, as you can see in the third part of the documentary below.

Credit: VTV World, YouTube

Author

Lisa McDonald

CTT Categories

- Art & Archaeology