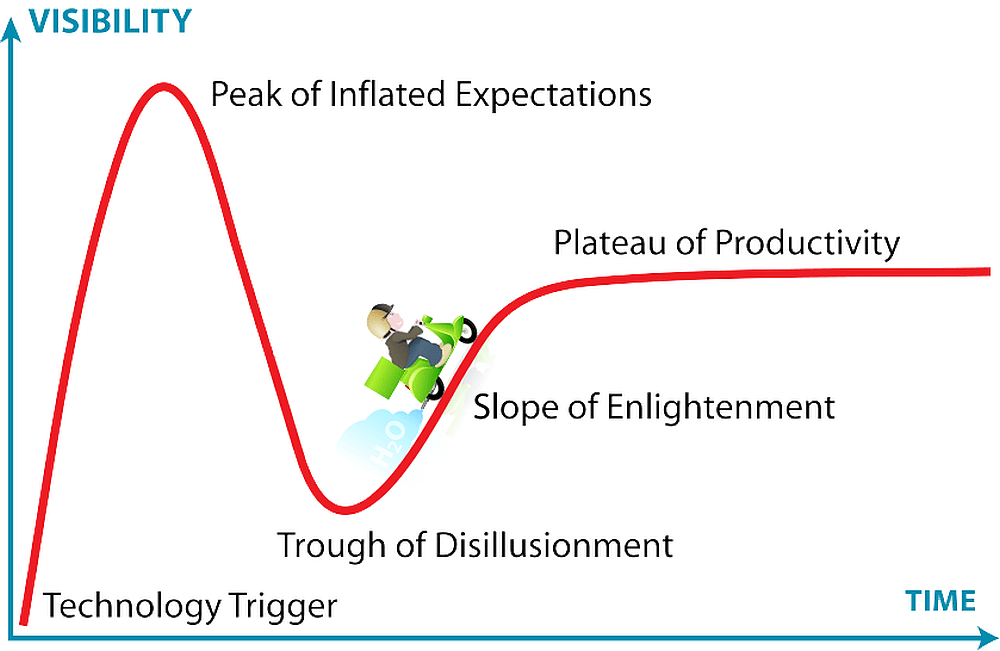

[Image above] This screenshot from a pressure test demonstrates how reinforced autoclaved aerated concrete (right) is less durable than traditional reinforced concrete (left). However, it is the lack of maintenance and replacement, not the material’s fundamental design, that is causing buildings to crumble right now in the United Kingdom. Credit: Guardian News, YouTube

The old adage “prevention is better than cure” is a fundamental principle of modern healthcare. Yet governments around the world repeatedly fail to apply this same wisdom to infrastructure construction and maintenance.

For example, the United States has deferred more than $1 trillion in maintenance for the nation’s aging infrastructure, according to a 2019 report by nonprofit Volcker Alliance. This lack of investment has led to numerous catastrophic failures, such as levee failures during Hurricane Katrina (2005), the I-35W bridge collapse in Minneapolis (2007), and the ongoing Flint water crisis (2014–present).

While in some cases these failures are due to design flaws, more often than not, the failure is due to pushing the materials beyond their intended lifespan. Such is the case right now with reinforced autoclaved aerated concrete (RAAC) buildings in the United Kingdom.

Aerated concrete, also called cellular concrete, is a lightweight and porous construction material that consists of about 80% air. Air is introduced into the mixture through different methods, and RAAC refers to the subset of aerated concretes that were fabricated via autoclaving (a pressurized steam curing process) and then reinforced with metal rods.

As explained in a May 2023 CTT, aerated concrete has several advantages over traditional concrete, such as being easier to transport, easier to machine, and a less carbon-intensive production process. However, aerated concrete easily absorbs water due to its porous structure, making it less durable than traditional concrete and endowing it with a shorter lifespan (~30 years for RAAC versus 50–100 years for reinforced concrete).

Because of its advantages, numerous countries become major producers and consumers of RAAC starting in ~1945, during the postwar building boom. In the U.K. specifically, RAAC was used in the construction of hundreds of buildings between the 1950s and mid-1990s, including schools, hospitals and theaters. But the popularity of RAAC faded following the publication of numerous studies showing the material’s risks, i.e., loss of strength when exposed to moisture and/or polluted air.

Simple math tells us that even the youngest RAAC buildings from the 1990s are reaching their 30-year lifespan. But even as roofs started to collapse (2018) and a government agency issued a safety briefing (2022), the U.K’s Conservative-led government slashed spending on infrastructure, as detailed in The New York Times.

“In a way, it’s a symbol of what you call broken Britain—or in this case, crumbling Britain,” says Caroline Slocock, director of think tank Civil Exchange and former senior civil servant under both Labor and Conservative governments, in the NYT article. “There has been over a decade of not recognizing the problem. And in not dealing with it, it keeps getting worse and worse.”

At the end of August 2023, the problem of crumbling RAAC infrastructure reached a head when the U.K. government published a list of schools that were confirmed to contain RAAC. This announcement led to more than 100 schools having to shut down or close off areas only days before the new school year started. As of September 19, the number of affected schools has increased to 174.

Though many in the media are blaming RAAC itself for the failures, construction experts are pushing back against this characterization of the material.

“The problem with these panels is not so much the material itself. It’s the fact that they’ve been used well beyond their expiry date,” says Juan Sagaseta, a reader in structural robustness at the University of Surrey, in a Wired article.

Alice Moncaster, professor of sustainable construction at the University of the West of England Bristol, agrees with Sagaseta, stating in the Wired article that it was politics, not the RAAC’s fundamental design, that got the U.K. to this point.

“It is a direct cause of lack of maintenance and replacement of public buildings … And this comes from the ‘small state’ approach that the Conservative Party in the U.K. have been pushing since 2010,” she says.

While the presence of RAAC in schools has garnered the most attention in recent weeks, as noted above, RAAC was used in the construction of all types of buildings. The video below shows how crumbling RAAC is affecting hospitals and other buildings across the country as well.

Credit: Channel 4 News, YouTube

Author

Lisa McDonald

CTT Categories

- Cement

- Market Insights