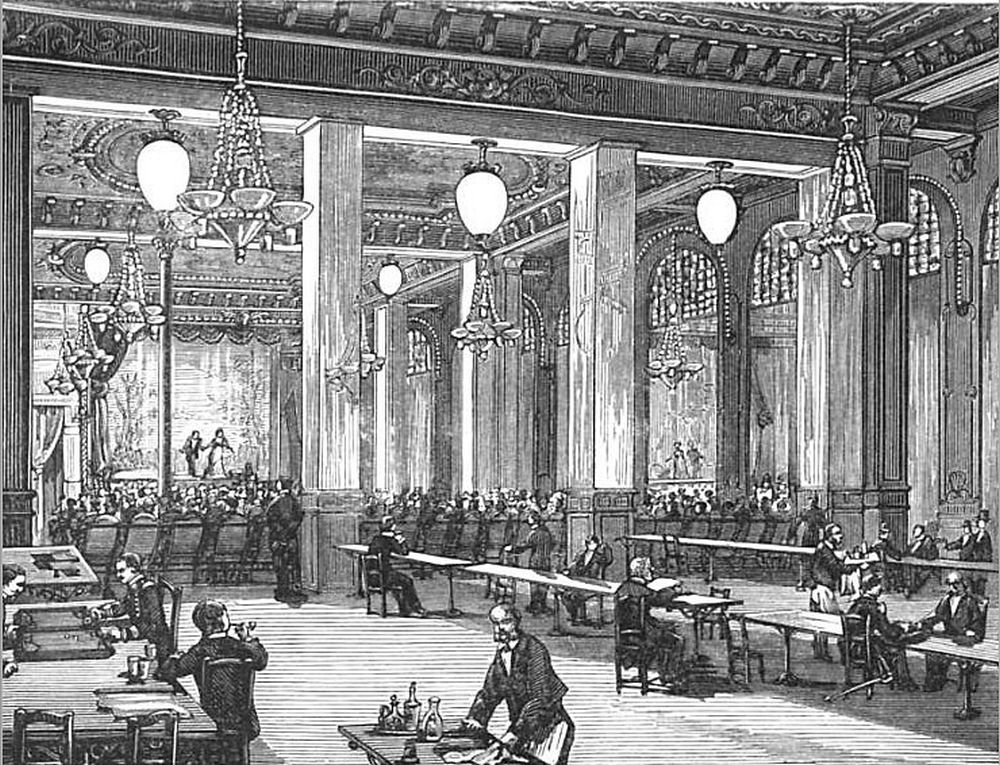

[Image above] Illustration of Yablochkov candles illuminating the Music Hall of la Place du Château d’Eau in Paris, circa 1880. Credit: Wikimedia (Public domain)

I was lucky enough to visit Paris once in December 2004, and I look forward to someday visiting in the spring and experiencing the City of Light’s dazzling boulevards and vibrant nightlife in full bloom. But for all its current glamor, Paris once had a very different moniker: the Crime Capital of the World.

This CTT will explore the long (and sometimes sordid) history of how Paris came to be known as the City of Light, starting in the late 1600s. The answer lies, in part, with a little-known technology that relied on ceramic engineering: the Yablochkov candle, the first widely adopted electric arc lamp.

History of urban illumination in Paris

As Paris’s first lieutenant general of police in 1667, Nicolas de la Reynie had a problem. At the time, Paris was a warren of small, unlit streets with a thriving criminal underworld. It was not safe for its residents, much less for its monarchy.

To clean up the city, La Reynie undertook an aggressive scheme of nighttime lighting. He urged all residents to leave candle lamps in their windows and installed lanterns at intersections. La Reynie’s work led to Paris becoming the first major city to be illuminated at night. By the end of his tenure, the city had close to 3,000 street lanterns.

In 1774, the Abbé Matherot de Perigny invented an oil lamp with a silvered reflector, which quickly replaced the candle lanterns. Gas lamps took over in the 1800s, and by 1870, there were 21,000 gas lamps in Paris, further expanding the reach of nighttime illumination.

The Yablochkov candle’s moment in the City of Light

The Yablochkov candle is an early type of electric arc lamp invented by Russian engineer Pavel Nikolayevich Yablochkov. Like many great discoveries, a serendipitous accident led to its development.

Arc lamps produce light when a high electric current crosses a gap between two conducting electrodes. English physicist Sir Humphry Davy invented the arc lamp in the early 1800s by using charcoal sticks and a battery.

By the late 1800s, various people were investigating ways to make the arc lamp more reliable. Yablochkov was one of those people, and his first project involved improving the Foucault regulator used in arc lamps, which was successfully applied to train lamps on the Moscow–Kursk Railway.

After his work on the railroad, Yablochkov opened a shop in Moscow along with fellow electrical engineer Nikolai Glukhov. In early 1875, Yablochkov was experimenting with the electrolysis of coal and accidentally created a bright arc between two parallel coal (carbon) rods. Those parallel rods were the inspiration for the Yablochkov candle, his improvement on the arc lamp.

By autumn of that year, Yablochkov moved to Paris to work with Louis Clément Francois Breguet, a well-known physicist. There, he perfected his arc lamp design—details in the following section— and on March 23, 1876, he was awarded French patent 112024 for his design.

The first public exhibition of the Yablochkov candle occurred in London in April 1876, and their first commercial use was at the Louvre Museum in October 1877. The most famous demonstration of the candle took place at the 1878 Exposition Universelle (World’s Fair), where 64 of them were used to light the Avenue de l’Opéra, Place du Théâtre Francais, and the Place de l’Opéra.

By the 1880s, Yablochkov candles had fallen into obsolescence due to the invention of incandescent lamps. Despite Yablochkov candles only having a moment in the spotlight, they still helped burnish Paris’s reputation as the City of Light.

The unique ceramic design behind Yablochkov candles

Electrode orientation and the use of insulating materials were the keys to the Yablochkov candle’s success. Prior arc lamp designs used direct current and short pieces of carbon oriented horizontally (end-to-end) on either side of an air gap. Because direct current caused the two rods to be consumed unequally, these arc lamps needed a mechanical regulator to maintain the correct distance between the rods. It was a complex design.

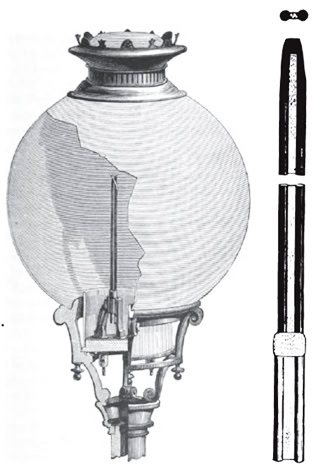

Illustration of the Yablochkov candle featuring two parallel carbon rods separated by an insulating material. Credit: Wikimedia, Luis Alberto Ferreira (CC BY-SA 4.0)

In contrast, the Yablochkov candle had the carbon rods oriented in parallel (side-by-side) and separated by an insulating material, typically clay or plaster of Paris. When a current was applied, an arc formed at the exposed end of the carbon rods. The intense heat of the arc reaction gradually melted the insulating material, exposing more of the rod. The choice of alternating current also made these arc lamps much more efficient because they were consumed evenly and did not need a regulator.

Yablochkov candles had a few inherent flaws, which led to their eventual replacement with incandescent lightbulbs. For example, even with four or six pairs of carbon rods, the lamps had a short lifespan of only 12 hours at most. They could not be reused and had to be replaced daily. The burning carbon produced carbon monoxide, and the arc lamps emitted harmful ultraviolet light. The lamps also made a buzzing noise and produced radio frequency interference.

Despite only a brief period of commercial success, the Yablochkov candle and its ceramic heart helped lay the foundation for the ubiquitous electric lighting all of us enjoy today. It stands as a testament to the power of materials science in urban development and cultural identity.

Author

Becky Stewart

CTT Categories

- Education

- Material Innovations

Related Posts

Ohio Creativity Trail: Heisey Glass Museum

January 13, 2026

Celebrating the US Semiquincentennial: Ohio Creativity Trail

December 16, 2025