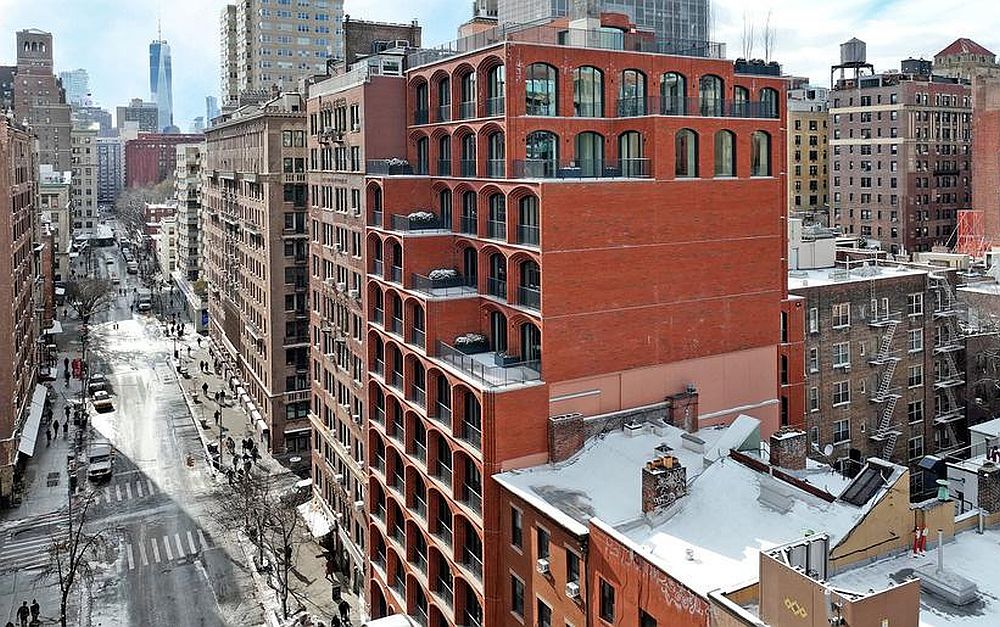

[Image above] A section of the Jinshanling Great Wall, which is one of the best-preserved parts of the Great Wall built during the Ming dynasty. Credit: DarthAvatar / Shutterstock

Roman concrete is a paradigm of resilient construction, with some structures still standing tall nearly 2,000 years after creation. But there are lessons to be learned from other early societies as well on building structures that last. For example, many structures from China’s Ming Dynasty (1368–1644)are so exceptionally durable that they can resist modern bulldozers and seismic shifts.

The secret to the Ming structures’ resilience is not just the brick or stone blocks; it is the biomortar bonding the blocks together. While I was researching for the three-part CTT series about brick, I discovered that the Great Wall of China was held together with sticky-rice mortar. As someone who enjoys sticky rice at the dinner table, the idea of it as a structural adhesive was intriguing.

Built more than 400 years ago, the sections of the Great Wall from the Ming Dynasty used a mixture of slaked lime and sticky-rice soup as the mortar. This CTT looks at how this ancient mortar provided superior mechanical strength and durability compared to pure lime mortars. Its composition offers profound lessons for modern sustainable ceramic construction.

Sticky rice: The secret ingredient in Chinese construction

Mortar is not just a decorative finish. The strength of a masonry wall is the result of interfacial bonding between the ceramic unit and the binder. Adding a small quantity of sticky rice to standard lime mortar creates a colloidal suspension with specific surfactant-like properties.

Sticky rice is primarily composed of amylopectin, a highly branched polysaccharide (in other words, a starch). Starch is an effective glue for some applications. In this mortar, the amylopectin does more than form a simple adhesive; it lowers the apparent surface tension of the mix and improves the workability (or Bingham plastic behavior). This change in rheology prolongs the setting time and allows the mortar to penetrate the capillary pores of medium-fired bricks more deeply. As a result, a strong mechanical interlock is developed that prevents delamination—a critical factor for the long-term structural integrity of high-mass ceramic walls.

The science: Molecular self-assembly at room temperature

The amylopectin in sticky-rice mortar interacts chemically with the slaked lime, or Ca(OH)2. The hydroxyl groups in the amylopectin bind to the calcium to form an organic–inorganic bioceramic, similar to the way avian eggshells form.

- Nucleation and growth: Amylopectin forms a molecular template, regulating the carbonation reaction [Ca(OH)2 + CO2 → CaCO3 + H2O]. Without amylopectin, calcite crystals grow into large, brittle rhombohedrons. With it, the crystallization is inhibited and redirected, resulting in a dense network of tiny, uniform nanocrystals that penetrate into the brick or stone and tightly bind the mortar to its substrate.

- Mineralogical phases: Research suggests the organic additive stabilizes vaterite, a precursor mineral phase that eventually transforms into a more compact, stable calcite structure. This transformation facilitates a form of densification that mimics liquid-phase sintering, but it occurs at ambient temperatures through chemical precipitation rather than kiln-firing.

- Green strength: The amylopectin provides significantly higher green strength—the structural integrity of the material before it has fully set—allowing ancient masons to build taller and faster without fear of slumping.

Amylopectin helps keep the calcium carbonate crystals small and more uniform in shape. The chemical changes give the mortar high fracture toughness and reduced water permeability.

An important quality of the amylopectin in the sticky-rice mortar is its thermal expansion compatibility. If the mortar and the ceramic brick or stone expanded and contracted at vastly different rates, the structures would have delaminated centuries ago. The result is a deep mechanical interlock that prevents delamination during thermal expansion. By matching the expansion rates of the substrate, the structure avoids the internal stresses that cause modern repairs to fail.

Performance and durability: Surviving the centuries

Sticky-rice mortar has been used in China for at least 1,500 years. Its popularity peaked in the Ming Dynasty and helps explain why so many Ming-era buildings have survived earthquakes and the ravages of time. The Nanjing city wall and the Shouchang bridge are two other examples of ancient structures held together with this mortar.

Recent research highlights two key areas of the mortar’s resilience:

- The wet–dry cycle: Although the organic components can introduce complex strain profiles, they function as an environmental barrier coating. Amylopectin induces pore-size refinement, shifting the microstructure from large macropores to smaller, disconnected micropores. Even when microcracks form, the mortar acts as a sealant, preventing the washing away effect that destroys standard lime.

- Beyond mortar: The Great Wall is not just brick; much of it has an earthen core. Sticky-rice paste reinforces these cores through nanoscale infiltration, turning loose soil into a plastic, resilient matrix that resists freeze–thaw cycles and salt corrosion.

Modern implications: The future is bioinspired

In modern ceramic science, the studies of polymer-derived ceramics and bioinspired ceramic composites are major frontiers. Sticky-rice mortar is a functional ancestor to macro-defect-free (MDF) cements and specialized ceramic pastes.

By considering sticky-rice mortar as a biopolymer-reinforced calcium carbonate ceramic, we elevate it from an ancient folk method to advanced composite engineering. Using such green binders can significantly reduce the carbon footprint of the CO2-heavy cement industry while providing a biocompatible method for restoring heritage sites.

Sticky-rice mortar is far more than a historical curiosity; it represents a sophisticated intersection of biology, chemistry, and ceramic engineering. Ancient builders were essentially performing wet chemistry and molecular self-assembly in their mixing troughs long before we had electron microscopes to witness the results. As we look for the next generation of ecofriendly building materials, the most advanced solution may be an ancient one.

Author

Becky Stewart

CTT Categories

- Art & Archaeology

- Construction