[Image above] Renewed interest in molten salt reactor technology has led researchers at Pacific Northwest National Laboratory to work on solutions for the design, construction, and operation of full-scale molten salt reactors. Credit: Pacific Northwest National Laboratory, YouTube

Nuclear power is having a resurgence in popularity as a source of low-carbon energy. However, traditional fission reactors use enriched uranium as fuel and produce highly radioactive solid waste that must be stored for centuries. These drawbacks make it difficult to get permission for new reactor construction—all the way from local zoning permits up to regulatory approval. These challenges are not just a problem in the United States. There are similar regulations in Germany, Japan, India, and the United Kingdom, among other nuclear-capable countries.

Yet there is another type of nuclear reactor that has been conceptualized almost from the beginning of nuclear technology: molten salt reactors (MSRs). These reactors are a type of non-light water reactors, meaning they are not dependent on water for cooling. Instead, these reactors are cooled with molten salts rather than water and can use fluid fuel as well.

These differences make MSRs inherently safer. Why, then, are these reactors not more commonly used? In this blog, we’ll look at the advantages and challenges of MSRs and the high-performance ceramic materials being developed to make these designs a practical reality.

History of molten salt reactors

You may be wondering why, if MSRs are safer than current reactor designs, countries are not using them exclusively. That question can be answered almost entirely by the Cold War.

Nuclear technology was developed as a power source in the first half of the 20th century, in an era when the most compelling use case was to make a giant bomb. This meant that nuclear reactor technologies that supported weapon development became the preferred designs.

Oak Ridge National Laboratory in Tennessee had a very successful MSR program through the 1960s, which resolved the main technical hurdles to commercial MSR deployment. However, the program was terminated by President Nixon in 1972 in favor of breeder reactor technology.

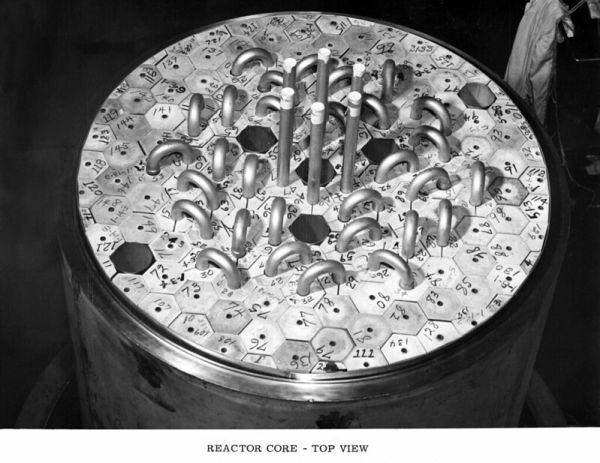

The Aircraft Reactor Experiment (ARE), shown above, was a molten salt reactor design with a beryllium oxide reflector. Its operation as part of the Aircraft Nuclear Propulsion program in November 1954 led to the development of several reactors, including the Molten Salt Reactor Experiment. Credit: Oak Ridge National Laboratory, Flickr (CC BY 2.0)

Breeder reactors convert nonfissile materials, such as uranium-238 and thorium-232, to fissile materials, such as plutonium-239 and uranium-233, respectively. Breeder reactors can produce more fissile materials than they consume, while not using up the valuable stock of uranium-235, which was needed for nuclear weapons. Plutonium-239 is also commonly used in thermonuclear bombs.

The most common type of reactor in use today is the pressurized water reactor, such as those used at Fukushima in Japan. The main drawbacks to this design are the relatively short fuel lifetimes (three to seven years) and safety concerns—in the case of a total electrical failure of both the power supply and cooling system, a nuclear meltdown may be impossible to prevent.

So, against the background of renewed interest in nuclear power as a low-carbon energy source, molten salt reactors are again being considered.

Advantages of MSRs

Molten salt reactors operate at lower pressure than pressurized water reactors (PWRs), using molten salts as the coolant rather than pressurized water. Although this design confers engineering benefits, the molten salt is quite corrosive. Essentially, you are swapping the challenge of high-pressure engineering for the challenge of high-corrosivity engineering.

Nonetheless, MSRs enjoy other substantial advantages compared to PWRs. For example, because they are low-pressure systems, MSRs can be miniaturized more easily than PWRs. Plus, they can use a variety of fuels and coolants (including some ceramic fuels—more on that later). Additionally, they operate at higher temperatures, providing better efficiency in electricity generation. The thermodynamic efficiency of MSRs ranges from 45–50%, in contrast to the efficiencies of 33–35% in traditional reactors. MSRs also have a greater margin of passive safety. If the power to the reactor fails, the fuel drains away under gravity, eliminating the potential for an accidental meltdown.

One promising MSR model uses the nonfissile material thorium as a fuel. Thorium is much more abundant than uranium on Earth, and it happens to be a byproduct of monazite mining, which is the main ore for rare earth elements (REEs). Typically, 6–7% of monazite is thorium, and 55–60% is REEs. Because REEs are so valuable, recovery of thorium from monazite is economical and helps reduce mine waste.

Additionally, though thorium itself is not fissile, it can be used to fission plutonium-239 sourced from spent conventional nuclear fuel, thereby disposing of nuclear waste.

High-performance ceramic materials in MSRs

The high temperature of the molten salt coupled with the corrosivity of the coolant and fuel demand materials that can operate for many years without maintenance. In many MSRs, the reactor vessel and the coolant system are constantly exposed to radiation. When a repair is needed, the fuel salt must be drained and flushed out thoroughly before any work is done.

Advanced ceramic materials such as silicon carbide and its composites have both the temperature tolerance and corrosion resistance to function in MSRs at the desired level of performance and safety. These materials are also radiation tolerant and, thus, can be used for structural components in the MSR. But the combined effects of radiation and corrosion cause eventual damage to the silicon carbide parts, too—hardening the ceramic and making it brittle. Understanding why and how this happens is one of the key knowledge gaps left to overcome in MSR designs using ceramics or ceramic composites.

In the wake of the Fukushima nuclear disaster, a lot of research has been aimed at the development of accident-tolerant fuels. Such fuels are another area where silicon carbide ceramics can be used. MSRs featuring salt-cooled solid fuel cores can use tristructural isotropic (TRISO) particle fuel. In these particles, a uranium fuel pellet (uranium nitride, uranium oxide, or uranium carbonate) is coated with layers of ceramic and carbon-based materials to prevent the release of fission products. These fuels further increase the safety margins of MSRs. TRISO fuels cannot melt at the temperatures present in the reactor, preventing a core meltdown.

Nuclear fuel design is a key determinant in the size and configuration of the reactor. Next-generation nuclear reactors are similar in design to their PWR predecessors, and anywhere that ceramic materials can be used in PWRs, they can be used in advanced reactors.

MSRs: Future directions and research opportunities

Interest in MSR technology is steadily growing, as evidenced by government entities such as Pacific Northwest National Laboratory (PNNL) expanding their laboratory capabilities to research this technology. PNNL will host its annual Molten Salt Reactor Annual Program Review on April 22–24, 2025.

Funding opportunities for MSRs are growing, too. For instance, MIT Technology Review named a molten-salt cooled reactor company that uses TRISO fuel to its list of 2024 Climate Tech Companies to Watch. The company, Kairos, will receive U.S. Department of Energy funding to build its test reactor in Tennessee. Examples of other companies developing molten salt reactor technology can be seen here.

China is currently building the world’s first commercial thorium MSR in Gansu province, near the Gobi Desert. An advantage of MSRs in desert regions is that they are not cooled by water. The reactor, with a capacity of approximately 100 MW, is due to enter service in 2030.

Additional challenges to commercialization remain, for instance, design safety standards and MSR-specific supply chains do not exist. Fortunately, these challenges are not insurmountable. Examples of other industries that built supply chains after a significant breakthrough include telecommunications and solar panels.

Ultimately, molten salt reactors are a promising technology to help support climate pledges and goals of net-zero carbon emissions.

Author

Becky Stewart

CTT Categories

- Energy

- Market Insights