[Image above] View from Sidon, Lebanon, which previously was a primary city-state in the ancient Phoenician civilization. Remnants of a Phoenician winemaking site near the city revealed that Phoenicians, not Romans, may be the original innovators of hydraulic plaster. Credit: Monik-a / Shutterstock

From the self-healing concrete of Rome to the world’s first synthetic pigment, Egyptian blue, numerous ancient Mediterranean civilizations are known for their contributions to the field of engineered ceramics, far before this discipline became a distinct field of study.

Yet there are other Mediterranean societies and cultures whose discoveries and innovations are equally notable, but their status as the originators of these inventions has faded from public consciousness.

Take the Phoenician people, for example. This ancient civilization, which existed between approximately 1550 to 300 BCE, was based on the east coast of the Mediterranean. The Phoenicians were organized into large, independent city-states that formed a strong coastal trade front. Though they were not necessarily a unified country, their major cities included Byblos, Sidon, Tyre, and Berot, which all fall under what we now know as Lebanon and Syria.

Approximate extent of Phoenician settlements and trade routes till 800 BCE. Credit: Peter Hermes Furian / Shutterstock

Despite knowing little about the Phoenicians compared to other ancient civilizations, they are remembered as the dominant maritime power in the Mediterranean between 1100 and 200 BCE, playing a key role in the export of cedar and pine wood, dyed cloths, embroideries, wine, metalwork and glass, and dried fish. This trade was supported through the use of an alphabetic writing system that the Phoenicians developed, which became the basis for the alphabet we use in Western culture today.

Notably, the name “Phoenician” comes from the Greek word for the civilization, “phoinix.” This word has several meanings, including the color crimson—possibly a nod to the distinct, sought-after reddish purple dye that Phoenicians created from snail shells.

The Phoenician reign eventually fell into collapse after the Persians and Greeks conquered Tyre and Rome destroyed the Phoenician trading colony Carthage in the Punic Wars. Historians widely believe that the remaining Phoenicians dispersed and assimilated to neighboring cultures, which could be why some Phoenician innovations—as you’ll learn below—have been attributed to other ancient civilizations.

Rome (and Phoenicia) wasn’t built in a day

Although Rome played a significant role in the fall of the Phoenician confederation as the two civilizations fought for dominance over the Mediterranean, both saw an overlap in their innovations and spread of ideas. While many of Rome’s strengths were displayed inland, they understood the value of water in order for an urban population to thrive, which is demonstrated through the 11 aqueducts they engineered to bring fresh water into the city.

Other notable inventions by the Romans include water-resistant concrete, roads, the Julian calendar, Roman numerals, and bound books, among a variety of inventions for social and public welfare.

As masters of sailing and sea fare, the Phoenicians also considered water to be sacred, and even built religious temples near freshwater springs, which then led to urbanization in the surrounding areas. One example is the Temple of Kothon in the Phoenician site Motya, off the coast of Sicily, which collected water underneath in an artificial basin through canals.

The coastal Phoenicians also excelled at shipbuilding and navigation, conducting advanced trading practices, and working with materials such as metal, glass, and wood. The Phoenicians are also credited with developing early forms of glassblowing techniques.

Reshaping the history of hydraulic plaster

The Romans have been credited with invention of hydraulic plaster, but new evidence published in Scientific Reports suggests that the Phoenician people may have been ahead of the Romans on this concept.

Hydraulic plaster is a type of lime plaster that hardens when exposed to water, as opposed to non-hydraulic plaster, which hardens and sets when exposed to air.

Archaeologists recently excavated the remnants of a Phoenician winemaking site in Tell el-Burak, southern Lebanon, dated between 725–350 BCE. The winemaking facility features a grape treading basin connected to a fermentation vat that can hold nearly 1,200 gallons of liquid.

A closer analysis of the site’s artifacts led by Eberhard Karls University of Tübingen in Germany revealed that the Phoenicians had sealed the structures with plaster reinforced with individual pieces of reused pottery. These findings show that the Phoenicians not only had the technological expertise to develop advanced hydraulic plaster but were also environmentally conscious.

The ceramic aggregates of the pottery reacted to the lime binder of the plaster, forming a more durable pozzolanic material that would not crumble when met with water. (A pozzolanic material is either siliceous or silico-aluminous and reacts with calcium hydroxide when water is present to form cementitious compounds.)

Due to the maritime culture of the Phoenicians, it follows that they would have developed a type of plaster that would be strengthened in the presence of water, especially given the fact that they also erected buildings and temples around fresh water sources.

Additionally, the authors of the paper suggest that the migration and expanse of the Phoenician people contributed to their spread of ideas and innovations, which is likely how the idea of hydraulic plaster went on to be adopted in Roman applications.

“The discovery that ceramic fragments were deliberately added to the lime plaster to enhance its hydraulic properties reveals a sophisticated level of technological innovation consistent with broader Mediterranean practices,” the authors write in the paper. “This technique, widely diffused in the Greek world and perfected by the Romans, enabled the production of high-quality plaster and mortars through the addition of ‘pozzolanic material’ like ceramics.”

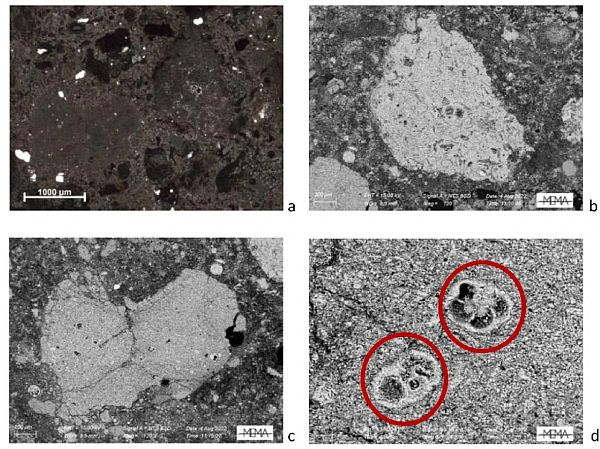

Thin section microphotographs of two thermally altered limestone fragments in sample SA3: (a) Polarizing microscope; (b, c) Backscattered electron images at high magnification; (d) Backscattered electron image showing a particular section of limestone with visible micro-fossiliferous content. Credit: Amicone et al., Scientific Reports (CC BY 4.0)

The Phoenicians are not the only ancient civilization that engaged in pottery recycling practices. Another new study by University of Thessaloniki researchers recently unveiled the ways that people from Neolithic Dispilio, Greece, repaired and restored pottery more than 7,000 years ago.

Out of 1,700 ceramic pieces excavated at Dispilio, 231 of them showed signs of restoration while more than 100 individual parts were reworked for other uses. The researchers found that the way the pottery was reused evolved and became more advanced over time, which further substantiates the idea that ancient eastern civilizations such as Phoenicia engaged in recycling.

While the evidence of recycled pottery in the Phoenician winemaking facility points to sustainable and resource-efficient thinking, University of Tübingen archaeologist Silvia Amicone also emphasizes the Phoenicians’ deliberate, clever choice of reinforcing the plaster with pottery pieces to make it stronger.

“The presence of ceramic aggregates wasn’t just about recycling waste—it was a technological choice to produce water-resistant, durable plaster,” she says in a press release.

The researchers hope that the discovery of hydraulic plaster in these Phoenician structures will shed more light on Phoenician technological advances and their contributions to the Iron Age Mediterranean.

The open-access paper, published in Scientific Reports, is “Innovation through recycling in Iron Age plaster technology at Tell el-Burak, Lebanon” (DOI: 10.1038/s41598-025-05844-x).

Author

Helen Widman

CTT Categories

- Art & Archaeology

- Construction