[Image above] Credit: Shestak Vera / Shutterstock

Even though most of the Earth’s surface is covered by water, we know surprisingly little about the ocean that supports all life. Fundamental questions such as where the ocean’s water came from and how oxygen is produced far below the waves remain open for debate and discussion.

The ocean’s role in the evolution of complex life is another fundamental question that perhaps is less understood than our textbooks would have us believe. In general, many of the Earth’s significant geochemical and biological events can be linked to the ocean’s carbon cycle and oxygenation. The former refers to the continuous movement of carbon through different environmental compartments, including the atmosphere, the ocean, and the biota (animal and plant life). The latter refers to the processes by which the ocean gains and maintains dissolved oxygen, which is vital for marine life.

It is generally accepted that two major oxygenation events occurred roughly 2.4–2.1 billion years and 800–540 million years ago, respectively, and catalyzed the development of global geological, geochemical, and biological processes that paved the way for the diversification of life. Many theories suggest these events were aided by large amounts of dissolved organic carbon (DOC) in the ocean, or carbon-containing molecules that serve as an energy source for marine microbes and a major carbon reservoir.

Some studies, such as here and here, reject the large DOC reservoir hypothesis. They suggest that the oxygenation events mainly relied on other aspects of the carbon cycle or entirely different mechanisms rather than the respiration (microbial breakdown) of DOC.

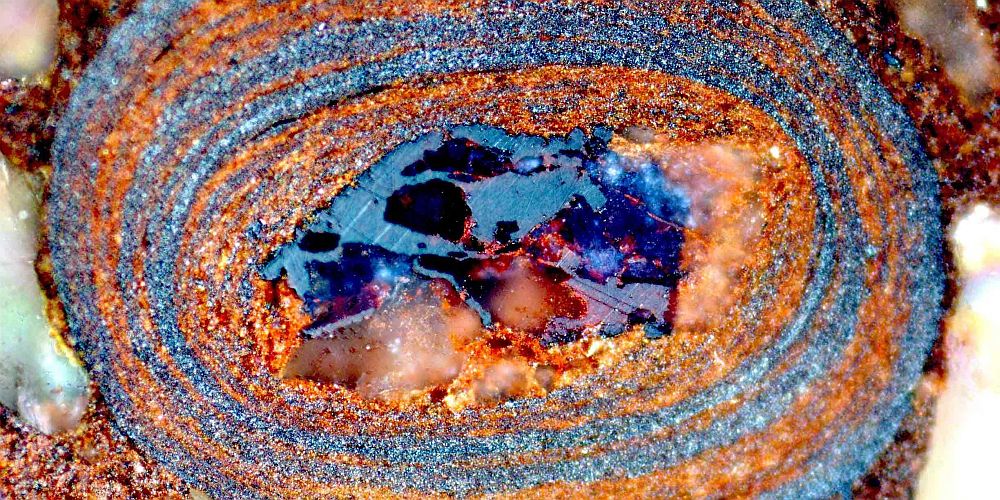

Finding support for these alternative theories is difficult, however, because there is little direct evidence available from these events that occurred millennia ago. But researchers led by ETH Zürich in Switzerland have now identified a unique proxy to estimate the amount of DOC available in the primordial ocean: tiny egg-shaped stones of iron oxide.

Cross-section of an egg-shaped iron oxide stone, which ETH Zürich researchers used to estimate the amount of dissolved organic carbon in the ocean millions of years ago. Credit: Nir Galili, ETH Zürich

As explained in an ETH Zürich press release, these micrometer-scale stones formed layer by layer as they were pushed across the ocean floor by waves. In the process, organic carbon molecules adhered to them and became part of the crystal structure.

The researchers examined these impurities in the iron oxide stones and determined that DOC levels fluctuated significantly during three distinct evolutionary periods of Earth’s history:

- Near modern levels of 660 billion metric tons in the late Paleoproterozoic to Mesoproterozoic Eras (~2 to 1 billion years ago).

- Decreased by about 90−99 wt.% in the Neoproterozoic Era (~1,000 to 541 million years ago).

- Returned to near-modern levels in the Paleozoic Era (~541 to 252 million years ago), where it has remained until today.

These findings differ from all other DOC models, which predict either a large DOC reservoir that shrunk over time or a DOC reservoir that remained about the same size throughout history. As a result, “We need new explanations for how ice ages, complex life, and oxygen increase are related,” says lead author Nir Galili, past doctoral candidate at ETH Zürich and now principal investigator at Weizmann Institute of Science, in the press release.

The open-access paper, published in Nature, is “The geologic history of marine dissolved organic carbon from iron oxides” (DOI: 10.1038/s41586-025-09383-3).

Author

Lisa McDonald

CTT Categories

- Basic Science

- Environment