[Image above] Example of a Late Medieval Period religious ring. Historical research on the trade of metal supplies and objects often overshadows studies on the practices, recipes, and supplies of clays used by metallurgists of the time. Credit: Birmingham Museums Trust (CC BY-SA 4.0)

For the first time since 2013, the Unified International Technical Conference on Refractories (UNITECR) is being held in North America!

UNITECR is a biennial international conference that contributes to the progress and exchange of industrial knowledge and technologies concerning refractories. This year, UNITECR will be held in Chicago, Ill., from March 15–18. (Only four days away!)

As an industry-oriented conference, the schedule of events is jam-packed with presentations showcasing recent advancements and developments in refractory ceramics, as well as lectures outlining future needs of the industry. The history of refractory ceramics leading up to today, however, is one topic that will not be extensively covered.

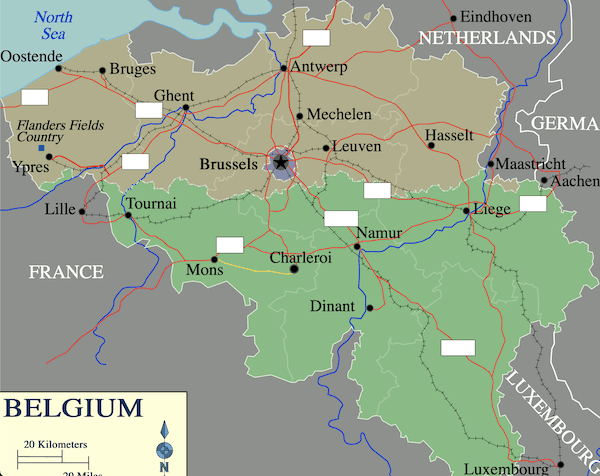

So, in preparation for UNITECR 2022, today’s CTT covers a small part of that history, which researchers in Belgium and France explored in a recent paper.

The practices of metallurgical workshops in 15th century Europe

The Late Middle Ages or Late Medieval Period was the period of European history lasting from about 1300 to 1500 CE. Though this period is often characterized by the hardships wrought by a series of famines, plagues, and warfare, this period is also considered the start of the Renaissance, a time of great progress within the arts and sciences.

Through written sources and archaeology, it is known that large medieval foundries existed during this period to produce brass and essential household objects, such as cauldrons or candlesticks. While it appears these large-scale production sites were concentrated in certain regions, such as the Meuse Valley, other cities had smaller workshops to produce copper-based dress accessories and other small personal objects for local markets.

However, knowledge of the smaller workshops remains largely incomplete, despite the discovery of thousands of the small everyday objects in excavations across Western Europe and even “pioneer” archaeological research in Paris, France (Katona et al., 2007, Thomas et al., 2008, Bourgarit and Thomas, 2012); Pisa, Italy (Carrera, 2018); and London, England (Egan, 1996).

In 1994, excavations conducted by the Royal Archaeological Society of Brussels led to the discovery of a foundry from the Late Middle Ages that produced these small copper-based accessories. Located in the former Duchy of Brabant, the remains of this Belgium-based foundry provide access to the daily life of a workshop, “revealing the products manufactured, the techniques and the materials used, including the alloys and the refractory ceramics,” the researchers write.

To better understand the practices of this smaller workshop, the researchers selected a total of 19 metallurgical ceramic samples, including casting molds and crucibles, and 27 copper-based scraps, including sheet metal cuttings and as-cast objects. They then characterized the materials using several analysis methods, including petrography using polarizing light microscopy and scanning electron microscopy, energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy, X-ray diffraction, and particle induced X-ray emission.

The analyses, in conjunction with written sources, placed the Brussels workshop in a wider network of raw material circulation and know-how related to their use.

For example, while ceramic samples such as molds and furnace walls were made from local clay, which was not particularly refractory, the crucibles were made from clay sourced from the Meuse Valley, which has recognized refractory qualities. Whether this refractory clay was imported to Brussels as volumes of extracted clay or already shaped crucibles, however, is unknown as both possibilities are reflected in written sources.

“For instance, crucibles for smelting silver passed through the Bapaume toll (south of Arras and east of Cambrai) before 1202 (Tailliar, 1849, p. 19),” the researchers write. “[Other] texts document the export of the ‘Andenne clays’ since the beginning of the 14th century, sometimes over long distances, as far as Arras in 1306 (±170 km) or Dijon, notably in 1380 at the request of the founder Colard Joseph (±350 km, Thomas, 2017, p. 126–7).”

In addition, analyses of the crucibles indicated that brass was produced by the cementation process, which requires a zinc ore that is found in the Meuse Valley as well as further east.

Beyond the materials themselves, the researchers also highlighted possible evidence of techniques for fabricating refractory products crossing long distances. Specifically, a practice common in Meuse Valley workshops was to add crushed old crucibles, or grogs, as a nonplastic temper to improve the refractory qualities of new crucibles. Analyses of crucibles located at the Brussels workshop revealed potential experimentation with adding a layer of local nonrefractory clay to the interior of the vessels to make them last longer.

“The application of local clay and not [Andenne] refractory clay could be an argument in favor of imported crucibles, but the coating is not systematic and the sample size of crucibles is probably too small to have a definitive conclusion,” they write.

The researchers conclude by noting that the study “sheds light on the circulation of materials, particularly refractory clay, and not only the flow of produced objects. … [it also] suggest the acquisition of specific skills, whether for the preparation of the clay, or the elaboration of brass with the cementation process.”

Ultimately, “This observation invites us in future research to take a closer look at the origin of the clays used by metallurgists to draw up their trade networks, too often in the shadow of metal supplies.”

The paper, published in Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports, is “Practices, recipes and supply of a late medieval brass foundry: The refractory ceramics and the metals of an early 15th century AD metallurgical workshop in Brussels” (DOI: 10.1016/j.jasrep.2022.103358).