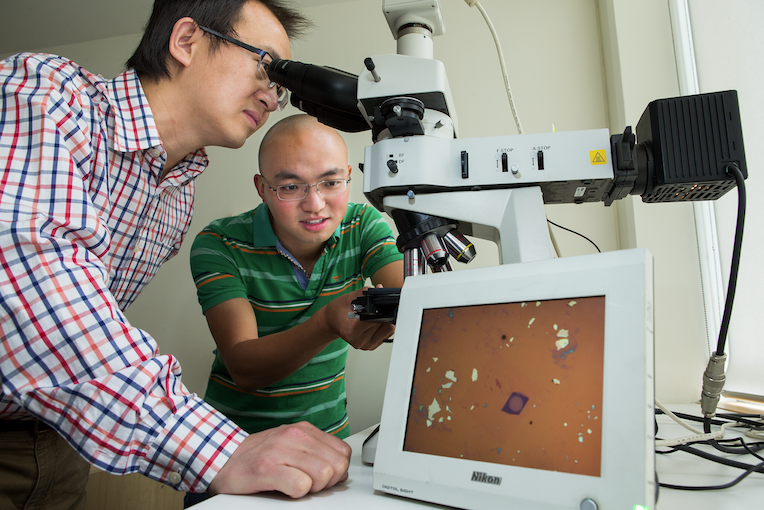

[Image above] Yuerui Lu (left) and Jiong Yan (right) from ANU Research School of Engineering examine what they describe as “the world’s thinnest lens, one two-thousandth the thickness of a human hair.” The lens is the purple circle that appears on the screen in the foreground. Credit: Stuart Hay; ANU

We expect our consumer electronic tech to do increasingly more for us. We want our smartphones, laptops, and tablets thinner, more durable, and flexible with sharp mega-pixel displays. We expect our cameras to be smaller and more versatile without sacrificing image quality.

We want more, better, thinner, faster, and stronger. And we want it now… Oh, and it should fit neatly into our back pockets, if that’s not too much trouble.

That’s a tall order for scientists and engineers in the tech industry in pursuit of those ideals.

(Sidebar: Check out emerging tech trends from this year’s Consumer Electronics Show, a global consumer electronics and technology tradeshow held every January in Las Vegas.)

When it comes to developing ultrathin lenses, scientists at Australian National University (Canberra, Australia) may have changed the game.

The team created what it describes as “the world’s thinnest lens, one two-thousandth the thickness of a human hair,” which could revolutionize flexible computer displays and miniature cameras, according to a recent ANU press release.

Lead researcher Yuerui Lu from ANU Research School of Engineering says the team’s discovery hinged on the remarkable potential of molybdenum disulfide crystals.

Molybdenum disulfide is a type of chalcogenide glass that is popular for high-tech applications because of its flexible electronic characteristics. “This type of material is the perfect candidate for future flexible displays,” Lu says in the release. “We will also be able to use arrays of microlenses to mimic the compound eyes of insects.”

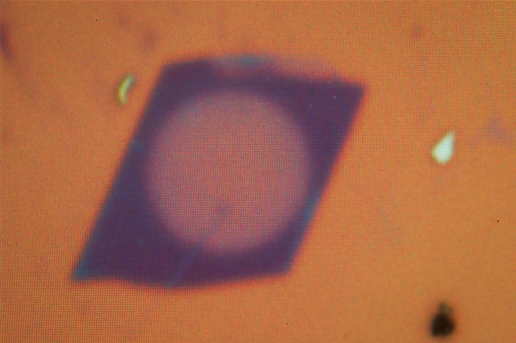

The team created their new ultrathin lens from a 6.3-nm-thick crystal—9 atomic layers—which they peeled off a larger piece of molybdenum disulfide with sticky tape. Then they made a 10-μm-radius lens using a focused ion beam to shave off the layers, atom by atom, until they fashioned the lens into a dome shape, according to the release.

Magnified image of ANU’s ultra-thin lens made from a crystal 6.3-nm thick. Credit: Stuart Hay; ANU

“Molybdenum disulfide is an amazing crystal,” Lu adds. “It survives at high temperatures, is a lubricant, a good semiconductor, and can emit photons too. The capability of manipulating the flow of light in atomic scale opens an exciting avenue towards unprecedented miniaturization of optical components and the integration of advanced optical functionalities.”

The team also discovered that single layers of molybdenum disulfide—0.7-nm-thick—had remarkable optical properties, appearing to a light beam to be 38 nm, or 50 times thicker. Known as “optical path length,” this property determines the phase of light and governs interference and diffraction of light as it propagates, the release explains.

For comparison’s sake, molybdenum disulfide crystals’ refractive index—the property that measures the strength of a material’s effect on light—has a high value of 5.5. That significantly outshines the refractive index of diamond (2.4) and water (1.3).

Looks like the solution to next-generation ultrathin lenses is crystal clear.

The open-access paper, published in Light: Science and Applications, is “Atomically thin optical lenses and gratings” (DOI: 10.1038/lsa.2016.46).